A 10,000-word in-depth analysis of Polygon's evolution: Can its former glory return through AggLayer and the CDK?

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

A 10,000-word in-depth analysis of Polygon's evolution: Can its former glory return through AggLayer and the CDK?

Markets often do not price in technological changes before they are implemented and take effect at scale.

Authors: Saurabh Deshpande, Sidd Harth, Decentralised.co

Translation: Yangz, Techub News

In March 2020, the market experienced an “unprecedented” black swan event. The financial world was shaken by the pandemic, and the Federal Reserve printed massive amounts of dollars to stimulate the economy. In this environment, Bitcoin, Ethereum, and several other tokens experienced some of their most glorious moments. But beyond price, a profound technological transformation reshaped how Ethereum scales.

Back in 2020, when Ethereum was still far from solving its scalability issues, Polygon (then known as Matic Network) launched as an application-specific scaling solution using the Ethereum Virtual Machine (EVM). From 2020 through early 2021, Polygon stood out among Ethereum scaling solutions as one of the few that could deliver high-quality applications—such as Aave—at extremely low fees on Ethereum.

Between 2021 and 2023, competition for Ethereum scaling intensified significantly. During this period, Optimistic Rollups (OR) launched products before ZK Rollups (ZKR). OR designs were less complex compared to ZKR. It was widely believed that high-performance, fully EVM-compatible ZKRs would take years to materialize. Although ORs were generally considered interim scaling solutions, they accumulated substantial user adoption and capital. In contrast, ZKRs lagged behind. This is evident in their respective Total Value Locked (TVL). As of April 11, ORs had approximately $35 billion in TVL, while ZKRs held around $3.7 billion.

While ORs gained popularity due to incentive mechanisms and new narratives, Polygon—one of the earliest solutions running as a sidechain—shifted focus toward ZK solutions, effectively ceding ground to ORs. Since ZKRs took time to launch, incentives were naturally delayed. By the time ZKRs finally arrived, ORs had already established themselves and captured user attention. Moreover, once ZKRs launched, their user experience was nearly indistinguishable from ORs, making it an uphill battle for ZKRs to draw attention.

Polygon Labs now offers a diverse suite of solutions, including a PoS chain, multiple upcoming ZKR implementations, and developer toolkits. To outsiders, Polygon’s strategy appears confusing—neither doing the right thing at the right time nor clearly focused today, seemingly trying everything at once. Yet upon deeper examination, I realized the significance of how these pieces fit together. This article will explore the evolution of the Polygon ecosystem and its outlook over the coming months.

The Need for Speed

No one forgets the era of Crypto Kitties—unique digital cats that could be bred and traded, bringing a sense of community to Ethereum. In December 2017, some kitties sold for over $100,000, and transactions consumed more than 10% of Ethereum’s total gas usage. The phenomenon even made headlines on BBC. However, it also highlighted Ethereum’s limitations at the time: amid high demand and soaring prices, ordinary users couldn’t afford exorbitant gas fees.

Clearly, Ethereum needed massive scalability upgrades in 2017. A natural thought arose: if a chain processes 12 transactions per second, can we split it into multiple independent chains? If there are 100 such chains, each processing 12 transactions per second, the network could handle 1,200 transactions per second. As the number of chains increases, so does scalability potential.

This is the broad concept of base-layer “sharding.” Shards are essentially chains running in parallel with smaller-scale counterparts. However, ensuring seamless interoperability to integrate these shards into Ethereum is just as challenging as scalability itself. For example, when users need to execute cross-shard transactions involving applications, interactions between chains become critical. This implies splitting validator sets into multiple groups to validate different chains.

While sharding remains the ultimate goal, Ethereum must take several necessary intermediate steps in the meantime—building blocks toward a sharded architecture. These include state channels, Plasma, and others.

Beyond sharding, another distinct approach began to emerge: what if instead of splitting validators, we reduce their computational burden? This is precisely the purpose of rollups. Rather than consuming Ethereum resources (gas) for every transaction, rollups use Ethereum only to publish batches of transactions. Thus, computation required to change state (viewing Ethereum’s state as account balances, smart contracts, and externally owned accounts) occurs off-chain, saving Ethereum’s resources. With rollups, Ethereum no longer directly interacts with millions of consumers but instead handles a few rollups that each serve tens of millions of users. Rollups help Ethereum transition from B2C to B2B.

Of course, this isn’t easy. When Ethereum validators no longer perform computations, how do users know the party executing them is honest? Normally, we could run our own node to verify whether validators correctly processed our transactions—but we don’t. Ultimately, we choose to trust Ethereum’s validators.

When transferring or swapping assets, validators modify Ethereum’s state—adjusting account balances, for instance. When this computation moves off-chain, users essentially place trust in the operator of that layer. Now, if we claim these layers are mere extensions of Ethereum, users shouldn’t be forced to trust anyone beyond Ethereum’s validators. That layer bears the responsibility of proving, in some way, that its actions comply with Ethereum’s rules.

How different rollups execute computations and prove correctness to Ethereum largely defines their type. ORs submit their computation results along with data needed to replay transactions (the results posted on Ethereum). Until someone challenges execution, any submitted result is assumed correct—hence the term “optimistic.” Validators typically have seven days to dispute a result. Note that, as of June 2024, only Optimism has implemented fraud-proof functionality; all other ORs lack this feature. Optimism has a first-stage fault/fraud proof system where, if the fault-proof system fails for any reason, a security council can intervene.

The other major category is ZKR. Zero-knowledge technology allows us to prove anything without revealing details about what is being proven. Instead of publishing all data for verifiers to replay transactions, ZKRs submit validity proofs to Ethereum.

Ethereum—The Anchor for L2s or Scaling Layers

Today’s Ethereum has grown alongside evolving protocols and applications. Some projects adapted; others did not. The story of Matic Network (now Polygon) exemplifies this perfectly. Thanks to Ethereum’s growth, Polygon has also thrived.

Since Ethereum’s launch in 2015, the landscape of crypto assets and blockchains has changed dramatically. Ethereum’s scaling roadmap underwent a pivotal shift at the end of 2020 when Vitalik published his vision centered on rollups. Ethereum’s development can thus be divided into two eras—with rollups marking the boundary. If Ethereum is the anchor, then L2s must follow.

Clearly, Ethereum needs massive scaling to become the “world computer.” Before understanding Ethereum’s scaling evolution, we should revisit the general meaning of scalability. Scalability means extending Ethereum’s security guarantees. Regardless of method, we must rely on Ethereum’s security to some extent. That is, Ethereum L1 should retain final authority over the state of scaling layers.

Before Ethereum committed to rollups, developers proposed various alternative scaling approaches: state channels, Plasma, sidechains, and sharding.

Among these, Plasma resembles sidechains. Plasma is a chain capable of independently executing transactions and periodically publishing compressed data to Ethereum. However, this introduces a data availability (DA) issue. Only Plasma operators possess the full historical data; Ethereum full nodes only see compressed summaries. Therefore, users must trust operators to maintain data availability. In short, Plasma’s security relies on the root chain (Ethereum). Fraud proofs and disputes are resolved according to root chain rules.

Data availability solutions typically separate consensus data from transaction data. As chains scale, storing and processing state becomes increasingly difficult. DA solutions address scalability by decoupling the consensus layer from the data layer. The consensus layer handles transaction ordering and integrity, while the data layer stores transaction data and state updates.

Sidechains are independent chains with their own consensus and validator sets, periodically publishing data to Ethereum. Their key difference from Plasma lies in having independent validator sets based on different consensus mechanisms. Users must trust sidechain validators to preserve transaction integrity.

Compared to Plasma and sidechains, ORs improve in two ways:

-

First, ORs avoid data availability issues by publishing all data on Ethereum.

-

Second, users don’t expand their trust assumptions—they don’t need to trust a new set of operators or validators.

This is why rollups are considered superior scaling solutions. One might say they’re improved versions of Plasma.

State channels resemble Bitcoin’s Lightning Network.

To illustrate simply, imagine Sid and Joel, who run sandwich and coffee shops next to each other. Due to the complementary nature of their goods, they decide to cross-sell and merge menus. When a customer orders a sandwich at Joel’s shop, he simply forwards the order to Sid. Payment happens only at the point of consumption. Both keep records internally but settle accounts at the end of the day.

Their mutual invoices resemble a channel between two nodes or accounts. At a high level, two users or apps can open an off-chain channel, transact freely, and settle on-chain when closing. This method requires opening multiple channels (on-chain transactions), which is hard to scale. As of June 2024, Lightning Network holds only about 5K BTC—meaning it cannot support more than 5K BTC in bidirectional transactions simultaneously.

Four Eras of Polygon’s Evolution

As one of the earliest scaling solutions to launch mainnet, Polygon’s development—both technically and ecologically—has gone through four phases:

-

Matic Network

-

Polygon Expansion

-

Embracing ZK

-

Aggregating Everything

Matic Network

Matic Network combined elements of Plasma and sidechain approaches. Validators stake MATIC tokens to validate transactions and secure the chain. As an additional security measure, snapshots of the chain’s state (checkpoints) are submitted to Ethereum. Once checkpoints are finalized on Ethereum, that state becomes immutable on Matic Network. After this point, blocks cannot be contested or reorganized.

In 2021, Matic Network rebranded as Polygon—but this was more than a name change. While Matic Network scaled Ethereum via a single-chain model, Polygon shifted toward a multi-chain ecosystem. To realize its vision of scaling Ethereum from multiple angles, Polygon introduced a Software Development Kit (SDK) to help developers port applications easily.

The SDK provides building blocks for larger software frameworks—in this case, different types of chains. Polygon SDK enables developers to build two kinds of chains: independent chains with their own validator sets, and chains relying on Ethereum for security (L2s).

Sidechains and enterprise chains seeking greater control over governance (who participates, who runs nodes, etc.) tend to choose the first option. Younger projects lacking resources or strong opinions about Ethereum’s security and consensus rules opt for the second.

In April 2021, shortly after Aave deployed on Polygon, Polygon’s TVL surged from around $150 million to nearly $10 billion. At the time, Polygon dominated most metrics—including active users and transaction volume. Even as of June 2024, Polygon PoS leads in daily active users. (Note: This figure should be viewed cautiously, as true active user counts are unknown. Data providers track active addresses, but one address doesn’t necessarily represent one user.)

Embracing ZK

As the Polygon PoS chain grew stronger, Polygon Labs explored further ways to scale Ethereum.

In 2021, when ZKRs were barely in development, Polygon Labs allocated $1 billion toward ZK development. They acquired Hermez Network, Miden, and Mir Protocol. Though all within the ZK domain, each team served unique purposes. Hermez focused on building a real-time zkEVM; Mir aimed to develop industry-leading proof technology to create a zkVM rollup with client-side proving.

At a time when most believed ZK technology would take three to five years to mature—and ORs were imminent (despite lacking fraud proofs)—Polygon Labs went all-in on ZK. This raises a question: Why did Polygon Labs pursue a longer-term path instead of deploying OR solutions first while researching ZK in parallel?

There are two reasons:

-

From scalability and security perspectives, ORs would surpass Polygon PoS as more advanced solutions.

-

Yet, there is consensus that ZKRs are the ultimate solution to outperform ORs.

Yes, once ORs implement fraud proofs, their security guarantees exceed those of sidechains like Polygon PoS. But for end-users, costs won’t differ much. Note that, aside from Optimism, no other OR has activated fraud proofs. Optimism began testing fraud proofs in March 2024. So, it will be some time before all ORs enable fraud proofs on their mainnets.

If viewed through a barbell strategy lens—where risk is distributed across very high-risk and very low-risk instruments—this reflects Polygon’s strategic posture.

Considering differences between ORs and ZKRs, and the fact that ORs must submit all transaction data to Ethereum, as OR transaction volume grows, data published on Ethereum increases almost linearly. In contrast, ZK proof size grows sub-linearly. Therefore, as transaction numbers rise, ZKRs are significantly more efficient than ORs.

Only a few hundred people globally likely possess the expertise to fully understand ZK technology and build infrastructure capable of handling hundreds of billions in value. ZK tech needs time to mature. Acquiring ZK-focused teams grants Polygon Labs rare tactical advantages.

Rollups and Trains

zkEVM is one of Polygon’s most important technologies. Why?

Imagine legacy blockchains as old-engine trains—slow, small-capacity, and expensive. Yet, over decades, they’ve built extensive rail networks. As one of the most widely adopted standards, EVM can be seen as this rail network.

ORs are like upgraded versions of these trains—using the same tracks but 10 to 100 times faster. But that’s insufficient. We need orders-of-magnitude improvements in speed and capacity for fast, low-cost travel. ZK Rollups aim to achieve this. The problem? These new trainsets can’t use old tracks—they require modifications. zkEVM enables ZK Rollups to work with existing EVM tools.

From a safety perspective, ORs cannot effectively prevent accidents. They operate under the assumption that accidents won’t happen. Fraud proofs are like Nolan films—they can’t prevent accidents but allow the system to rewind and fix things before they occur. In contrast, ZK technology prevents accidents altogether.

The EVM Equivalence Spectrum

Let’s dive deeper into zkEVM.

The analogy above explains why EVM compatibility matters. But compatibility isn’t binary—it exists on a spectrum. The prover is a crucial component of ZK systems. It proves an event occurred without revealing its details.

So why zkEVM? SNARK or STARK technologies enable cryptographic proofs. Both generate easily verifiable proofs that can confirm transactions occurred on a chain. To scale Ethereum, we use this tech to prove Ethereum-like transactions occurred on a layer. These layers are rollups; ZK tech allows rollups to compress transaction data by orders of magnitude, thereby scaling Ethereum. If the goal is to scale Ethereum, zkEVMs aim to prove execution in a way Ethereum’s execution layer can verify.

When a rollup is fully equivalent to Ethereum, it can reuse existing Ethereum clients and architecture. Full equivalence means the rollup maintains complete compatibility with Ethereum smart contracts and the broader ecosystem. For example, addresses remain the same, wallets like MetaMask work seamlessly, etc.

Proving things in a way Ethereum understands is challenging. When Ethereum was designed, ZK-friendliness wasn’t a priority. That’s why certain parts of Ethereum are computationally heavy for ZK proofs—increasing both time and cost to generate proofs. Thus, if the proof system uses Ethereum unchanged, it becomes unwieldy. Alternatively, the proof system can be lightweight but must build its own architecture tailored to Ethereum.

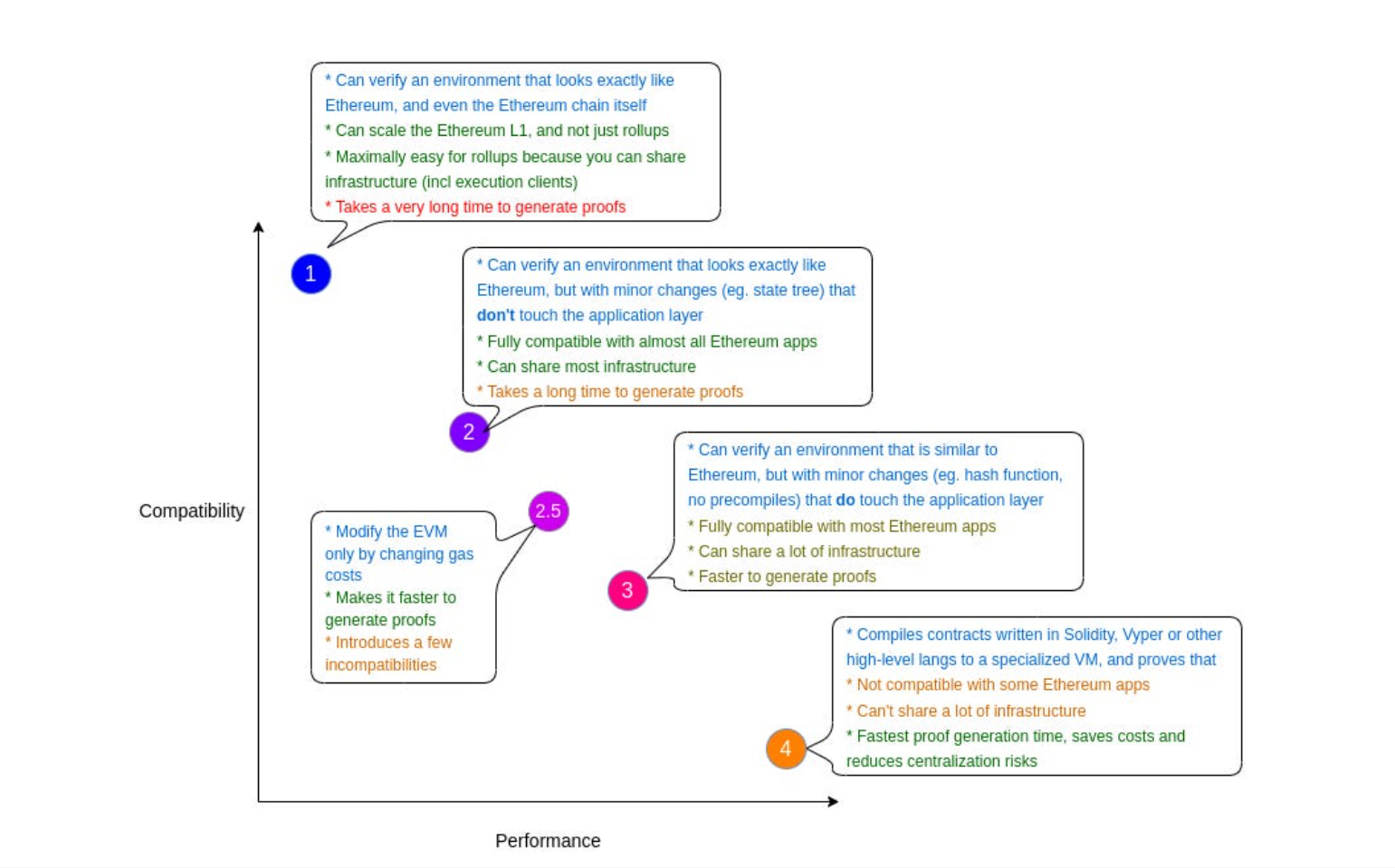

Therefore, different zkEVMs trade off ease of use of existing tools against proof cost and difficulty. Vitalik outlined existing zkEVM types in a blog post. Below are the categories. Type 1 offers strongest compatibility but worst performance; Type 4 offers weakest compatibility but best performance.

-

Type 1 – Fully equivalent to Ethereum.

-

Type 2 – EVM-equivalent but not Ethereum-equivalent. Requires minor tweaks to Ethereum to make proof generation easier.

-

Type 2.5 – Similar to Type 2 except for gas costs. Not all operations have equal ZK proof difficulty. This type increases gas costs for certain operations, encouraging developers to avoid them.

-

Type 3 – Modifies Ethereum to speed up provers, sacrificing some equivalence.

-

Type 4 – Compiles Solidity or Vyper source code into another language. This verifier abandons Ethereum compatibility entirely—the lightest-weight type. Its drawback: differs greatly from Ethereum. Everything changes—from addresses to wallet requirements. Starknet, for example, requires special wallets like Argent, and addresses look different.

Polygon Labs recently launched an upgrade introducing a new era of proof technology using Type 1 provers. Using Type 1 means any EVM chain—whether newly generated via Polygon CDK or an independent L1—can become a ZK L2 equivalent to Ethereum.

AggLayer & Polygon CDK: Aggregating Everything

No single EVM chain can bear the entire network load—that’s why we turn to L2s. Today, multiple L2s exist, but user growth and capital haven’t kept pace. Liquidity, users, and locked value are fragmented across L2s. In a way, L1 and L2 form a paradox: the base layer can’t scale, yet multi-chain ecosystems may dilute scale.

The solution lies in offering a service enabling seamless asset and information flow across multiple L1s and L2s—crucially, without rent-seeking or extractive fees—and ensuring chains retain sovereignty.

AggLayer was designed exactly for this. It enables secure, fast cross-chain interoperability. Chains connected to AggLayer share liquidity and state. Before AggLayer, moving assets across chains either required third-party bridges with trust assumptions and wrapped assets, or withdrawing from L2 to Ethereum then bridging—a process involving high fees and poor UX.

AggLayer eliminates friction in cross-chain transfers and creates an interoperable chain web. Currently, L2s can be seen as different contracts on Ethereum. Transferring funds from one L2 to another involves three distinct security zones: two L2 contracts and Ethereum.

In cross-chain transfers, security zones are part of the infrastructure where validator sets intersect. Validity checks and transaction forwarding occur at these junctions. Because of differing security zones, when you sign a transaction to move assets from one L2 to another, Ethereum gets involved. Assets first move from the source L2 to Ethereum, then to the target L2—three separate sequences or transactions or intents.

With AggLayer, the entire transfer becomes one-click. AggLayer hosts a unified cross-chain contract on Ethereum; any chain can connect to it. Ethereum sees one contract; AggLayer sees many chains. A ZK proof called “pessimistic proof” treats each connected chain skeptically, securing the total funds locked in the unified bridge. In other words, pessimistic proof is a cryptographic guarantee that one chain cannot compromise the entire bridge.

With AggLayer, transferring assets from one L2 to another no longer requires Ethereum’s involvement—since all L2s share state and liquidity. The three previous transactions/intents merge into one.

Suppose Sid wants to buy NFTs on Chain A, but all his assets are on Chain B. Before purchase, the cross-chain transfer from B to A can be fully abstracted via AggLayer.

Benefits of AggLayer:

-

Transforms zero-sum fragmentation of liquidity and users into cooperative relationships among chains.

-

Chains benefit from shared security and tools while retaining sovereignty—without needing to post bonds like earlier models (e.g., Polkadot).

-

Enables inter-chain interaction with lower latency than Ethereum.

-

Brings fungibility to cross-chain assets, improving UX. All activity happens within one cross-chain contract—no need for multiple versions of wrapped assets.

-

Better UX due to abstraction of cross-chain complexity.

Currently, rollups and validiums individually submit their chain states to Ethereum. AggLayer aggregates these states and submits everything as a single proof to Ethereum, helping save protocol gas costs.

Competition in the L2 space is fierce—Arbitrum, Optimism, Polygon, Scroll, Starknet, ZKsync—all vying for dominance. You can compete, but given the internet’s scale, we’re still early in crypto adoption. Finding cooperative strategies is often better.

Even game theory research suggests cooperation is almost always the best path for survival and growth. AggLayer’s positive aspects lie in its credible neutrality (not favoring any specific project; any chain can connect), and unified liquidity and state. Other multi-chain ecosystems charge fees across chains (and downstream users), whereas AggLayer is designed to minimize fees while delivering secure, low-latency cross-chain interoperability.

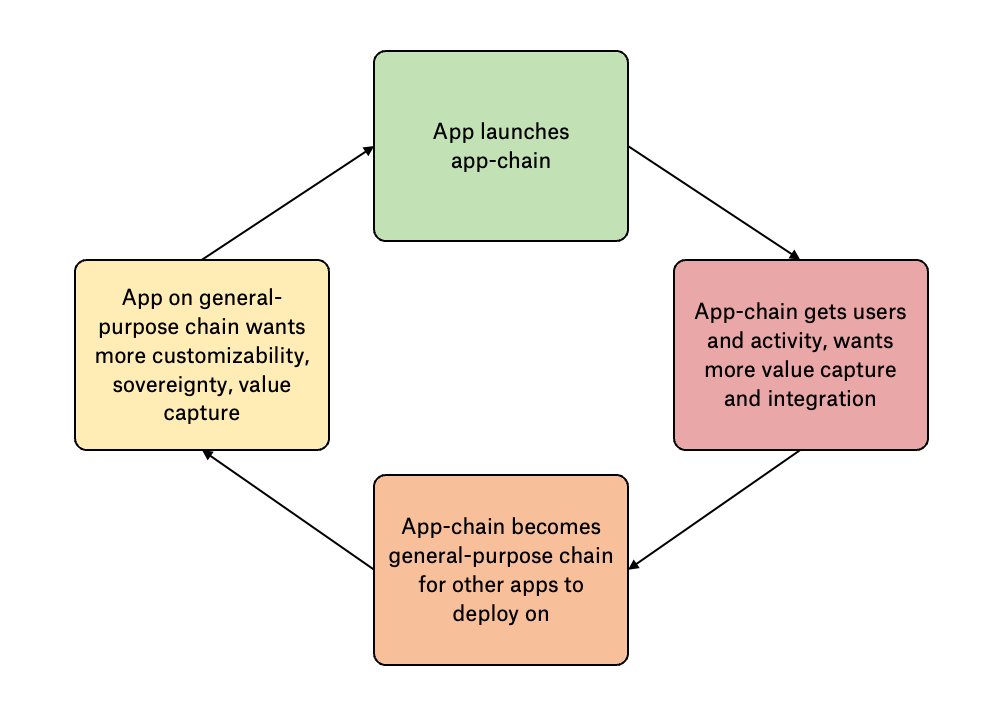

Recently, launching app-specific chains has become a common trend. Aevo, dYdX, and Osmosis exemplify this. Regarding this trend, Jon Charbonneau noted:

-

Apps need flexibility and sovereignty, so they launch their own chains.

-

App chains see growing users and activity, aiming to capture more value by allowing other apps to build on their chain.

-

Eventually, app chains evolve into general-purpose chains.

As Lanre mentioned, the market seems to favor apps launching app chains that later become general-purpose. Taken to the extreme, this trend may leave only a few general-purpose chains. While multiple chains can coexist, if liquidity and users remain constant and shared across chains, more chains mean worse overall crypto UX.

As previously argued, liquidity and users are spread across numerous L2s, resulting in poor liquidity on many. We need a solution to unify it all—AggLayer is a step in that direction.

There are many reasons apps desire dedicated blockspace. For example, during hot NFT mints on the same chain, trading apps shouldn’t compete for scarce blockspace. Liquidations or position closures shouldn’t be affected by other on-chain activity (in terms of fees or throughput). But if too many apps go down the app-chain route, fragmentation risks arise. Hence, AggLayer integrates these disparate chains. It’s a simple solution letting gaming chains and DeFi chains avoid direct blockspace contention while achieving cross-chain interoperability.

On one hand, AggLayer helps unify liquidity across chains; on the other, Polygon CDK enables chain creation.

Polygon CDK is a collection of open-source technologies evolved over years. It started as an SDK, transitioned to Supernets, and now takes its current form. Polygon CDK allows developers to build two types of L2s: Rollups and Validiums.

The most important feature of Polygon CDK is flexibility. When building a new chain (L2), developers can customize options across four parameters: VM, mode, DA, and gas token.

-

Virtual Machine (VM): the environment executing transactions. Polygon CDK lets developers choose different VMs, such as zkEVM.

-

Mode: choosing between Validium or Rollup. The difference lies in data published on Ethereum. Rollups publish compressed transaction data on Ethereum—making Rollup mode more secure. Validiums publish this data on a separate layer—like their own DA layer.

-

DA: a key component of scalability, separating consensus and data layers. Full nodes on chains like Ethereum and Bitcoin store all data to independently verify all transactions. Polygon CDK allows chains to build custom DA committees or use DA solutions like Celestia.

-

Gas Token Customization: chains can collect gas fees in their chosen token. For example, Polygon CDK allows developers to let users pay gas in their chain’s native token instead of ETH.

-

Sequencers are currently centralized. In the future, other teams or individuals may run sequencers.

Beyond modularity and sovereignty, building chains with CDK offers other benefits. Polygon CDK gives chains the option to use AggLayer’s single, unified cross-chain contract. This eliminates the need for multiple wrapped asset versions, improving UX for CDK-based app chains.

For example, using Polygon CDK, app chains for lending and derivatives can choose Rollup mode (all

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News