Vitalik: Inside the Mechanics of zk-SNARKs

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

Vitalik: Inside the Mechanics of zk-SNARKs

This article assumes you are already familiar with these two concepts and have a basic understanding of zk-SNARKs and their functions.

*Note: This article was written in February 2017

This article explains how the technology behind zk-SNARKs works. Previous articles on quadratic arithmetic programs and elliptic curve pairings are essential reading; this article assumes you already understand both concepts and have basic knowledge of what zk-SNARKs are and what they do. See also another introduction to zk-SNARKs, Christian Reitwiessner's article.

In earlier articles, we introduced quadratic arithmetic programs (QAPs), a method for representing any computational problem as polynomial equations. We also introduced elliptic curve pairings, which allow a very limited form of homomorphic encryption, enabling equality checks. Now, we will pick up where we left off and use elliptic curve pairings along with other mathematical techniques to enable a prover to demonstrate knowledge of a solution to a specific QAP without revealing any information about the actual solution.

This article focuses on the Pinocchio protocol by Parno, Gentry, Howell, and Raykova from 2013 (commonly referred to as PGHR13); there are variations in the underlying mechanisms, so practical implementations of zk-SNARK schemes may differ slightly, but the core principles generally remain unchanged.

First, let’s introduce a key assumption: the Knowledge-of-Exponent Assumption (KEA). We’ll use this assumption when explaining the underlying security mechanism.

KEA1: For any adversary A that receives inputs q, g, g^a and returns (C, Y) such that Y = C^a, there must exist an "extractor" A' that, given the same inputs as A, can return c such that g^c = C.

This assumption essentially means that if you receive a pair of points P and Q where P * k = Q, and you get another point C, then it is impossible to compute the corresponding point C * k unless C is somehow "derived" from P. This might seem obvious, but this assumption cannot actually be derived from any other assumptions typically used in proving the security of elliptic curve protocols (e.g., the discrete logarithm problem). Therefore, zk-SNARKs indeed rely on somewhat weaker security foundations compared to standard elliptic curve cryptography—though still strong enough that most cryptographers accept them.

Now, let’s see how we can use this. Suppose a pair of points (P, Q) falls from the sky, where P * k = Q, but no one knows the value of k. Now suppose I come up with another pair (R, S) such that R * k = S. Then, the KEA implies that the only way I could obtain such a pair is by multiplying P and Q by some factor r known to me. Also note that due to the remarkable properties of elliptic curve pairings, checking whether R * k = S does not require knowing k—it suffices to simply verify e(R, Q) = e(P, S).

Let’s do something more interesting. Suppose ten pairs of points fall from the sky: (P_1, Q_1), (P_2, Q_2), ..., (P_10, Q_10), all satisfying P_i * k = Q_i. Suppose I then give you a new pair (R, S) such that R * k = S. What do you know now? You know that R must be some linear combination: P_1 * i_1 + P_2 * i_2 + ... + P_10 * i_10, where I know the coefficients i_1, i_2, ..., i_10. In other words, the only way to arrive at such a pair (R, S) is by taking multiples of P_1 through P_10, summing them, and performing the same computation on Q_1 through Q_10.

Note that given any desired set of P_1 ... P_10 points for which you want to check linear combinations, you cannot actually create the associated Q_1 ... Q_10 points without knowing k. Conversely, if you do know k, you could create a pair (R, S) with R * k = S for any arbitrary R without forming a linear combination. Hence, the party creating these points must be trusted, and once the ten points are created, k must be securely deleted. This is the origin of the concept of “trusted setup” (Translator’s note: Trusted setup refers to a one-time initialization process performed when launching a zk-SNARK system, required only once).

Recall that a solution to a QAP consists of polynomials (A, B, C) such that A(x) * B(x) - C(x) = H(x) * Z(x), where:

A is a linear combination of a set of polynomials {A_1 ... A_m}

B is a linear combination of {B_1 ... B_m} using the same coefficients

C is a linear combination of {C_1 ... C_m} using the same coefficients

The sets {A_1 ... A_m}, {B_1 ... B_m}, {C_1 ... C_m}, and the polynomial Z are part of the problem statement.

However, in most real-world scenarios, A, B, and C are extremely large; for objects like hash functions with thousands of circuit gates, the polynomials (and their linear combination coefficients) may contain thousands of terms. Thus, instead of having the prover directly provide the full linear combination, we use the trick described above to prove that what they provide is indeed a linear combination, without revealing anything else.

You may have noticed that the above technique applies to elliptic curve points, not polynomials. Therefore, in practice, the following values are added during the trusted setup:

G * A_1(t), G * A_1(t) * k_a

G * A_2(t), G * A_2(t) * k_a

...

G * B_1(t), G * B_1(t) * k_b

G * B_2(t), G * B_2(t) * k_b

...

G * C_1(t), G * C_1(t) * k_c

G * C_2(t), G * C_2(t) * k_c

...

You can think of t as the “secret point” at which the polynomials are evaluated. G is a “generator”—a fixed random point on the elliptic curve that becomes part of the protocol. The values t, k_a, k_b, and k_c are “toxic waste,” numbers that must be destroyed at all costs; anyone possessing them could forge proofs. Now, if someone gives you a pair of points P, Q such that P * k_a = Q (recall: we don’t need k_a to verify this—we can perform a pairing check), then you know that what they’ve provided is a linear combination of the A_i polynomials evaluated at t.

So far, the prover must provide:

π_a = G * A(t), π'_a = G * A(t) * k_a

π_b = G * B(t), π'_b = G * B(t) * k_b

π_c = G * C(t), π'_c = G * C(t) * k_c

Note that the prover doesn’t actually need to know (and should not know!) t, k_a, k_b, or k_c to compute these values; rather, the prover should be able to derive them from the points added to the trusted setup.

The next step is to ensure that all three linear combinations use the same coefficients. We can achieve this by adding another set of values to the trusted setup: G * (A_i(t) + B_i(t) + C_i(t)) * b, where b is another number considered “toxic waste” and discarded after the trusted setup. Then, we let the prover create a linear combination using these values with the same coefficients and use the same pairing trick as above to verify that this value matches the provided A + B + C.

Finally, we need to prove that A * B - C = H * Z. We again perform a pairing check:

e(π_a, π_b) / e(π_c, G) ?= e(π_h, G * Z(t))

where π_h = G * H(t). If you can’t see the connection between this equation and A * B - C = H * Z, go back and re-read the article on pairings.

We've seen above how A, B, and C are transformed into points on an elliptic curve; G is just the generator (i.e., the elliptic curve point G corresponds to the number 1). We can add G * Z(t) to the trusted setup. Computing H is harder; H is merely a polynomial whose coefficients vary per QAP solution, making it difficult to predict in advance. Therefore, we need to add more data to the trusted setup; specifically, the sequence:

G, G * t, G * t², G * t³, G * t⁴, ...

In Zcash’s trusted setup, this sequence contains approximately two million elements; consider the computational effort needed to ensure H(t) can be computed. With this, the prover can supply all necessary information for the final verification.

One more detail remains. Most of the time, we don't just want to abstractly prove that a solution exists for a particular problem; rather, we want to prove correctness of a specific solution (e.g., prove: hashing the word "cow" one million times with SHA3 results in a hash starting with 0x73064fe5), or show that a solution exists under certain constraints. For example, in cryptocurrency implementations, transaction amounts and account balances are encrypted, and you need to prove knowledge of a decryption key k such that:

decrypt(old_balance, k) ≥ decrypt(tx_value, k)

decrypt(old_balance, k) - decrypt(tx_value, k) = decrypt(new_balance, k)

The encrypted old_balance, tx_value, and new_balance must be public since they represent concrete values visible at a given time; only the decryption key needs to remain hidden. Some subtle modifications to the protocol are required to create a “custom verification key” corresponding to specific input constraints.

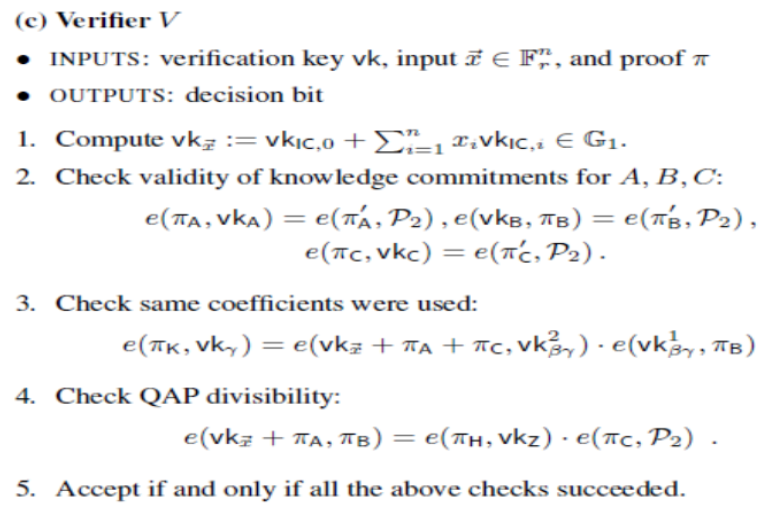

Now, let’s step back. Here is the complete verification algorithm, provided by Ben Sasson, Tromer, Virza, and Chiesa:

The first line performs parameterization; essentially, its function is to create a “custom verification key” for a specific problem instance with specified parameters. The second line checks the linear combinations of A, B, and C; the third verifies that the linear combinations share the same coefficients; the fourth checks that A * B - C = H * Z.

In summary, the verification process involves several elliptic curve multiplications (one per “public” input variable) and five pairing checks, one of which includes an additional pairing multiplication. The proof consists of eight elliptic curve points: one each for A(t), B(t), and C(t), a point π_k for b * (A(t) + B(t) + C(t)), and a point π_h for H(t). Seven of these points lie on the F_p curve (each 32 bytes, since the y-coordinate can be compressed to 1 bit); in the Zcash implementation, the eighth point (π_b) lies on the twisted curve F_p² (64 bytes), resulting in a total proof size of approximately 288 bytes.

The two most computationally intensive parts of generating a proof are:

- Computing (A * B - C) / Z to obtain H (algorithms based on fast Fourier transforms can do this in sub-quadratic time, but it remains computationally heavy)

- Performing elliptic curve multiplications and additions to generate the values A(t), B(t), C(t), H(t), and their corresponding pairings

Proof generation is difficult because, in zero-knowledge proofs, each individual binary logic gate in the original computation becomes an operation involving elliptic curve cryptography. This fact, combined with the superlinear complexity of fast Fourier transforms, means that creating a proof in a Zcash transaction takes roughly 20–40 seconds.

Another critical question: Can we make the trusted setup slightly less reliant on trust? Unfortunately, we cannot eliminate trust entirely; the KEA itself rules out the possibility of independently generating pairs (P_i, P_i * k) without knowing k. However, we can significantly improve security by using N-of-N multi-party computation—that is, constructing the trusted setup among N parties, such that security holds as long as at least one participant deletes their toxic waste.

To give you a sense of how this works, here’s a simple algorithm for taking an existing set (G, G * t, G * t², G * t³, ...) and “joining” your own secret, so that cheating would require both your secret and the previous secret(s).

The output set is straightforward:

G, (G * t) * s, (G * t²) * s², (G * t³) * s³, ...

Note that you can generate this new set knowing only the original set and s, and the new set functions identically to the old one—except that t * s now acts as the “toxic waste” instead of t. As long as neither you nor the person(s) who created the prior set fail to delete their toxic waste and later collude, the group remains “secure.”

Implementing this for a full trusted setup is much more complex due to multiple values involved and the need for multiple rounds of communication among participants. This is an active area of research: simplifying multi-party computation algorithms, reducing the number of rounds, and increasing parallelizability—because doing so would allow more participants to join the trusted setup. There’s good reason to believe that a six-party trusted setup might make some uneasy, whereas a setup involving thousands of participants is nearly trustless—if you’re truly paranoid, you can personally participate in the ceremony and ensure your own toxic waste is deleted.

Another active research direction is achieving the same goals without pairings and trusted setups. See Eli Ben-Sasson’s recent presentation (be warned: it's mathematically at least as complex as SNARKs!)

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News