The Prehistory of the Ethereum Protocol: Slowly Awakening from Nirvana

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

The Prehistory of the Ethereum Protocol: Slowly Awakening from Nirvana

This article aims to review the evolution of the Ethereum protocol from its inception to release.

Written on September 14, 2017

Editor's note: This article is Vitalik's recollection of the development history of the Ethereum protocol, recounting the story of how the Ethereum protocol evolved from its conception to initial release and iteration.

Although the core ideas behind today’s Ethereum protocol have largely stabilized over the past two years, Ethereum’s current vision and full form did not emerge overnight. After the launch of the Ethereum blockchain, its protocol underwent a series of significant evolutions and decisions.

This article aims to review the evolution of the Ethereum protocol from its inception to its release. The extensive work done by Geth, cppethereum, pyethereum, and EthereumJ in implementing the protocol, as well as the application and business history of the Ethereum ecosystem, will not be covered here.

Also outside the scope is the historical development of Casper and sharding research. Undoubtedly, we could write many more articles about various proposals that Vlad, Gavin, I, and others put forward and later abandoned—such as proofs-of-proof-of-work, hybrid multi-chain designs, hypercubes, shadow chains (a precursor to Plasma), chain fibers, multiple iterations of Casper, and Vlad’s rapidly evolving ideas on reasoning about incentives and properties of participants within consensus protocols. The stories behind these ideas are complex enough to warrant their own separate article. Therefore, they will not be discussed for now.

Let’s start with the earliest version—the one that eventually became Ethereum, though at the time it wasn’t even called Ethereum yet. In October 2013, during my visit to Israel, I spent a lot of time with the Mastercoin team and even suggested they add certain features. After deep reflection on what they were doing, I sent them a proposal suggesting ways to make their protocol more general-purpose, enabling support for more types of contracts without adding a large and complex feature set:

https://web.archive.org/web/20150627031414/http://vbuterin.com/ultimatescripting.html

Note that this version was vastly different from Ethereum’s later, broader vision: it focused purely on the technical breakthrough Mastercoin was attempting at the time—bilateral contracts. In such contracts, Party A and Party B jointly deposit funds, which can later be withdrawn based on formulas specified in the contract (e.g., “If X happens, give all funds to A; otherwise, give all funds to B”). The scripting language used to implement these contracts was not Turing-complete.

The Mastercoin team was impressed, but they had no interest in abandoning their existing direction to pursue this path. Meanwhile, I grew increasingly convinced this was the right approach. So around December, the second version emerged:

https://web.archive.org/web/20131219030753/http://vitalik.ca/ethereum.html

In this version, you can see the results of substantial refactoring—much of which came to me during a long walk through San Francisco in November. By then, I realized smart contracts had the potential to be fully generalized. Instead of a scripting language merely describing bilateral relationships, contracts themselves would become full-fledged accounts capable of holding, sending, and receiving assets, and even maintaining persistent storage (at the time, persistent storage was called “memory,” and the only temporary “memory” consisted of 256 registers). The language shifted from a stack-based virtual machine to a register-based one more aligned with my preferences. I had few objections, except that it seemed somewhat more complex.

The term “ether” literally meant ether (i.e., fuel, equivalent to gas). After each computational step, the balance of the contract invoked by a transaction would decrease slightly. If the contract ran out of funds, execution would halt. Note that this receiver-pays mechanism meant the contract itself had to require senders to pay fees. If the fee wasn’t paid, execution would immediately terminate. This version of the protocol allocated a limit of 16 free execution steps, allowing contracts to reject transactions that didn’t pay fees.

Up to this point, the Ethereum protocol was entirely built by me alone. However, from this moment onward, new participants began joining the Ethereum effort. So far, the most prominent contributor on the protocol side was Gavin, who first contacted me via a private message on about.me in December 2013.

Jeffrey Wilcke, lead developer of the Go client (then called “ethereal”), also reached out to me around the same time and began coding. Though his contributions leaned more toward client development than protocol research.

Gavin’s early contributions were twofold. First, you might notice that in the initial design, the contract call model was asynchronous: although Contract A could create an internal transaction to Contract B (“internal transaction” is Ethereum jargon—originally just called “transactions,” later renamed “message calls” or simply “calls”), the internal transaction wouldn’t begin executing until the first transaction had fully completed. This meant transactions couldn’t use internal transactions to retrieve information from other contracts; instead, they had to use the EXTRO opcode (similar to SLOAD for reading another contract’s storage), which was later removed with support from Gavin and others.

When implementing my original specification, Gavin naturally implemented internal transactions synchronously—he didn’t even realize there was a difference in intent. That is, in Gavin’s implementation, when one contract called another, the internal transaction executed immediately. Once that execution finished, the VM returned control to the calling contract and continued with the next opcode. Both of us found this approach superior, so we decided to adopt it as part of the official specification.

Second, a discussion between Gavin and me—during a walk in San Francisco (so precise details are forever lost to the tides of history, though perhaps one or two copies remain buried in NSA archives)—led to a restructuring of the transaction fee model, shifting from contract payment to sender payment and transitioning to a fuel-based architecture. Instead of consuming ether after each individual computational step, in this version, the transaction initiator pays a fee and receives a certain amount of fuel (essentially a counter for computational steps). Execution proceeds up to the fuel limit. If a transaction consumes all its fuel, the fuel is consumed, but the entire execution is reverted. This appeared to be the safest approach, as it eliminated all partial-execution attack vectors that contracts previously had to worry about. Any unused fuel at the end of execution would result in a refund.

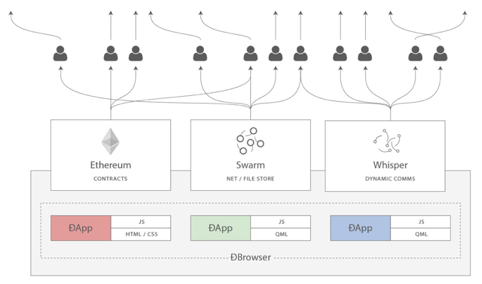

Gavin significantly and subtly shifted Ethereum’s vision: from a platform for building programmable money—platforms with blockchain-based contracts that hold digital assets and transfer them according to predefined rules—to a general-purpose computing platform. This shift began with subtle changes in focus and terminology, and intensified as we increasingly emphasized Web3 integration (viewing Ethereum as part of a decentralized technology suite alongside Whisper and Swarm, Figure 1).

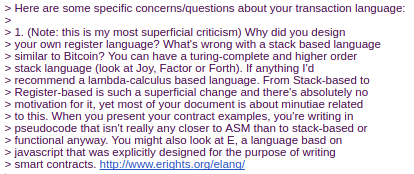

Around early 2014, we made additional modifications based on suggestions from others. After Andrew Miller and others proposed returning to a stack-based architecture, we ultimately did so (Figure 2).

Charles Hoskinson suggested switching from Bitcoin’s SHA256 to the newer SHA3 (or more precisely, keccak256). Despite some controversy, through discussions with Gavin, Andrew, and others, we settled on limiting the size of values in the stack to 32 bytes. The alternative—unbounded integers—remained under consideration, but posed a challenge: it was difficult to determine how much fuel operations like addition, multiplication, and others should consume.

Back in January 2014, our initial mining algorithm idea was something called Dagger:

https://github.com/ethereum/wiki/blob/master/Dagger.md

Dagger was named after the Directed Acyclic Graph (DAG), a mathematical structure used in the algorithm. The idea was that every N blocks, a new DAG would be pseudo-randomly generated from a seed. The underlying DAG would consist of a collection of nodes requiring billions of bytes to store. However, generating any single value within the DAG required computing only a few thousand entries. A Dagger computation involved fetching a number of values from arbitrary positions in this underlying dataset and hashing them together. This meant there was a fast way to compute Dagger—by storing the data in memory—and a slow, memory-light method—regenerating each needed value from scratch. Fast miners would use the former, making mining bandwidth-limited (in theory, consumer-grade memory is already highly optimized, making further ASIC optimization difficult), while light clients could verify using the slower, memory-friendly method. The fast method might take microseconds, while the slow one could take milliseconds—still feasible for light clients.

From there, the algorithm underwent several changes alongside Ethereum’s development. The next idea was Adaptive Proof of Work. In this scheme, proof of work would involve executing randomly selected Ethereum contracts, with a clever anti-ASIC twist: if ASICs were developed, competing miners would be incentivized to create and publish contracts that ASICs performed poorly on. No ASIC could match general-purpose computation because it would essentially just be a CPU. Thus, we could leverage these adversarial incentives to achieve proof of work that effectively performed general computation.

This idea later fell apart due to a simple reason: long-range attacks. An attacker could build a chain starting from block 1, filling it only with simple contracts. Notably, the attacker could design specialized hardware optimized for these simple contracts, allowing the attack chain to quickly overtake the main chain. So… back to square one.

The next algorithm was called “Random Circuit,” described in detail in a Google Doc. Proposed by me and Vlad Zamfir, and analyzed by Matthew Wampler-Doty and others, it aimed to simulate general computation in mining by executing pseudo-randomly generated circuits. This time, there was no solid evidence that something based on these principles couldn’t work. But computer hardware experts we consulted in 2014 were deeply pessimistic. Matthew Wampler-Doty proposed a SAT-solver-based proof of work, but it was ultimately rejected.

Finally, after circling back, we arrived at the Dagger Hashimoto algorithm, sometimes abbreviated Dashimoto. It borrowed heavily from Hashimoto, a proof-of-work mechanism proposed by Thaddeus Dryja that pioneered the concept of “I/O-bound proof of work,” where mining speed is primarily limited not by hash rate per second, but by megabytes per second that RAM can access. However, Dagger Hashimoto combined this mechanism with the DAG-generated dataset from Dagger that was friendly to light clients. After multiple refinements by me, Matthew, Tim, and others, these ideas coalesced into what we now call the “Ethash” algorithm.

By summer 2014, aside from proof of work needing until early 2015 to reach the Ethash stage, the protocol was quite stable, and its semi-formal specification had been published in Gavin’s Yellow Paper.

In August 2014, I developed and introduced the uncle block mechanism. This allowed Ethereum’s blockchain to have shorter block times and higher throughput while reducing centralization risks. For details on the uncle mechanism, refer to PoC6.

After discussions with the BitShares team, we considered using heaps as a first-class data structure—though ultimately didn’t implement it due to time constraints, and later security audits and DoS attacks taught us that securely implementing this feature at the time was far harder than anticipated.

In September, Gavin and I planned two major changes to the protocol design. First, in addition to state and transaction trees, each block would also include a receipt tree. The receipt tree would contain hashes of logs created by each transaction and intermediate state roots. Logs would allow transactions to create outputs stored on the blockchain and accessible to light clients. However, future state computations could not access these logs. This approach made it easy for decentralized applications to query events such as token transfers, purchases, exchange orders being created and matched, and ongoing auctions.

We also considered other ideas, such as extracting Merkle trees from the complete execution trace of a transaction to enable arbitrary content verification. After balancing simplicity and completeness, we chose to go with logs.

Second was the idea of precompiles. Precompiles solved the problem of making complex cryptographic computations available in the EVM without incurring EVM overhead. We also proposed many ambitious ideas about native contracts—where miners could vote to reduce gas prices for contracts they had better implementations of. Thus, contracts that most miners could execute quickly would naturally have lower gas costs. However, all these ideas were rejected because we couldn’t devise a cryptoeconomically secure enough way to implement them. Attackers could always create contracts performing cryptographic operations with backdoors, distribute the backdoors to themselves and allies, execute faster, then vote to reduce gas prices and exploit this to launch DoS attacks on the network. Instead, we opted for a less ambitious approach: simply specifying a small number of precompiles in the protocol for common operations like hashing and signature schemes.

Gavin was also a key early proponent of protocol abstraction—the idea of moving many parts of the protocol, such as ether balances, transaction signature algorithms, nonces, etc., into contracts within the protocol itself. The theoretical end goal was for the entire Ethereum protocol to be describable as simply applying function calls to a virtual machine with specific pre-initialized state. We didn’t have enough time to incorporate all these ideas into the initial Frontier release, but expected these principles to gradually be integrated through changes in “Constantinople,” Casper contracts, and sharding specifications.

These features were all implemented in PoC7. After PoC7, the protocol didn’t undergo major changes, except for minor but sometimes important adjustments. These details would be disclosed after security audits.

By early 2015, Jutta Steiner and others organized pre-launch security audits, including software code audits and academic audits. Software audits primarily targeted the C++ and Go implementations led by Gavin and Jeff, respectively. My Pyethereum implementation also underwent a basic audit. Of the two academic audits, one was conducted by Ittay Eyal (famous for “selfish mining”), and the other by Andrew Miller and members of Least Authority. Eyal’s audit led to a minor protocol change: the total difficulty of a chain would no longer include uncle blocks. The audit by Least Authority focused more on smart contracts, gas economics, and Patricia trees. It also resulted in several protocol changes. One smaller change was using sha3(addr) and sha3(key) as keys in the trees instead of raw addresses and keys—making worst-case attacks on the trees harder for attackers to execute.

Another important issue we discussed was the gas limit voting mechanism. At the time, we were concerned about the stalled debate over Bitcoin’s block size and wanted Ethereum to have a flexible design that could adjust over time as needed. But the challenge was: what was the optimal limit? My initial idea was a dynamic limit set at 1.5 times the long-term exponential moving average (EMA) of actual gas usage. Thus, in the long run, average blocks would be filled to 2/3 capacity. However, Andrew proved this mechanism could be exploited—specifically, miners wanting to raise the limit could include high-gas, low-computation-cost transactions in their own blocks, creating full blocks without incurring real costs. As a result, the security model of this mechanism was effectively equivalent to simply letting miners vote on the gas limit.

Unable to devise a better gas limit strategy, Andrew recommended explicitly letting miners vote on the gas limit, with the default voting strategy being 1.5 times the EMA. The reason was that we hadn’t figured out the correct way to set a maximum gas limit, and the risk of any specific method failing seemed far greater than the risk of miners abusing voting power. Therefore, we decided to simply let miners vote on the gas limit, accepting the risks of limits being too high or too low in exchange for flexibility and the benefit of miners collectively adjusting the limit quickly as needed.

After a mini hackathon with Gavin and Jeff, PoC9 finally launched in March. It was intended to be the final proof-of-concept version. We ran a testnet called “Olympic” for four months using the protocol intended for the mainnet. Meanwhile, we established Ethereum’s long-term roadmap. Vinay Gupta wrote an article—“Ethereum Release Process”—describing four stages of Ethereum mainnet development, giving rise to the now-familiar names: “Frontier,” “Homestead,” “Metropolis,” and “Serenity.”

The “Olympic” testnet ran for four months. During the first two months, we discovered many bugs across implementations and encountered issues like consensus failures. But by around June, the network had significantly stabilized. In July, we decided to freeze the code; on July 30, the Ethereum mainnet officially launched.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News