Vitalik: Hard Forks, Soft Forks, Defaults, and Mandates

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

Vitalik: Hard Forks, Soft Forks, Defaults, and Mandates

In the protocol upgrade mechanism, is it better to prefer soft forks or hard forks?

Author: Vitalik Buterin

Published on: March 14, 2017

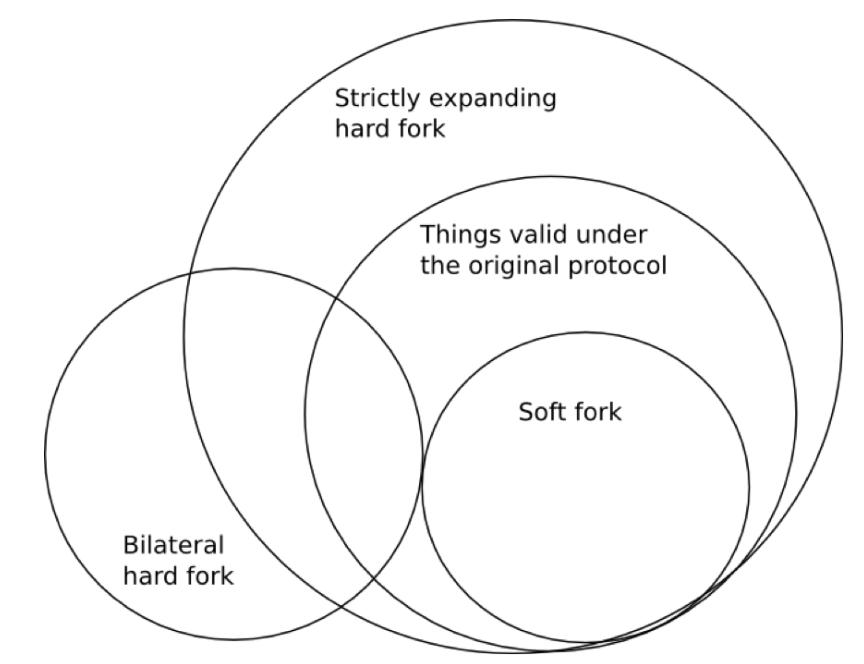

In blockchain discussions, one of the most important debates centers around whether soft forks or hard forks are preferable for protocol upgrades. The fundamental difference between soft forks and hard forks lies in how they alter protocol rules: a soft fork changes the rules by strictly reducing the set of valid transactions, so nodes following the old protocol can still remain on the new chain (assuming most miners/validators adopt the fork). In contrast, a hard fork allows previously invalid transactions and blocks to become valid, requiring users to upgrade their clients in order to stay on the post-fork chain.

There are two subtypes of hard forks:

1. Strictly expanding hard forks, which expand the set of valid transactions completely, making old rules effectively compatible with the new ones,

2. Bilateral hard forks, where neither rule set is compatible with the other.

Here’s a Venn diagram illustrating the types of forks:

The commonly cited advantages are as follows:

- Hard forks give developers more flexibility during protocol upgrades, as they don't need to ensure that new rules fit within the constraints of the old ones.

- Soft forks are more convenient for users, as no additional upgrades are required to remain on the new chain.

- Soft forks are less likely to result in chain splits.

- Soft forks, in practice, only require miner/validator agreement (even if users run old software, if nodes enforce the new rules, only transactions valid under the new rules will be included on-chain). Hard forks, however, require explicit user consent.

Additionally, a major criticism of hard forks is that they are “coercive.” This coercion does not refer to physical force but rather to network effects: if the network changes its rules from A to B, even if you personally prefer A, if most users favor B and switch to it, you must also switch to B in order to stay synchronized with the majority—regardless of your personal opposition.

Supporters of hard forks are often accused of attempting a “hostile takeover” of the network and “forcing” users to follow them. Furthermore, the risk of chain splits is frequently cited as evidence that hard forks are unsafe.

In my view, these criticisms are fundamentally incorrect—and in many cases, exactly backwards. This perspective isn’t specific to Ethereum, Bitcoin, or any particular blockchain; it arises from general system properties and applies broadly across all such systems. Moreover, the arguments below apply only to contentious changes, where at least one constituency (miners/validators or users) has significant opposition. If a change isn’t controversial, it can be implemented safely regardless of fork type.

First, let's discuss coercion. Any protocol change inherently alters the system in ways that some users may dislike. Especially when support isn't unanimous, changing the protocol inevitably displeases some users. Crucially, in nearly all cases, dissenters value staying in sync with the majority due to network effects more than their individual preference over the protocol. Thus, in terms of network effects, both fork types are coercive.

However, there is a crucial distinction: hard forks are opt-in, while soft forks leave users with no choice. To join a hard forked chain, a user must actively install software implementing the new rules. Users who oppose the change more strongly than they value network effects can theoretically remain on the old chain—and in practice, this has already happened.

This holds true for both strictly expanding and bilateral hard forks. However, in the case of a successful soft fork, there is no non-forked chain. Thus, soft forks are institutionally more coercive and less accommodating of separation, whereas hard forks have the opposite tendency. My personal ethical stance favors separation over coercion, although others may disagree (the most common argument being that network effects are extremely important, and essential for the "one coin" principle, though milder versions exist).

If I had to guess why soft forks are still considered "less coercive" despite this reasoning, I'd suggest it's because hard forks appear to "force" users to manually update software, while soft forks require no action. However, I believe this intuition is flawed. What matters isn't whether users must perform a simple bureaucratic step like clicking "download," but whether users are forced to accept a protocol change they fundamentally oppose. By this metric, as shown above, both fork types are ultimately coercive—and hard forks offer slightly more freedom to users than soft forks.

Now, let’s examine highly contentious forks, particularly those where miner/validator preferences conflict with user preferences. There are three main scenarios: (i) bilateral hard forks, (ii) strictly expanding hard forks, and (iii) so-called “user-activated soft forks” (UASFs). A fourth category—miner-activated soft forks without user consent—will be discussed later.

First, consider bilateral hard forks. In the ideal case, this scenario is straightforward: both coins trade on the market, and traders determine their relative value. From the ETH/ETC split, we have strong evidence that most miners allocate hash power according to price ratios to maximize profits, rather than based on ideological preferences.

Even if some miners ideologically favor one chain, enough profit-driven miners will likely exploit any mismatch between price and hash power ratios, bringing them into alignment. If a group of miners colludes to withhold mining on one chain, this creates an incentive imbalance that tends to correct itself.

Two edge cases exist. First, inefficient difficulty adjustment algorithms could cause mining profitability to drop when coin value falls, even if difficulty doesn’t adjust downward quickly. This makes mining unprofitable, and no miner will continue supporting the chain until difficulty rebalances. This is not the case with Ethereum, but it is very likely with Bitcoin. As a result, a minority-hashpower chain may never gain traction and eventually die. Whether this is good or bad depends on your view of coercion versus separation. Based on my earlier position, I believe such anti-minority-hashpower difficulty adjustment mechanisms are undesirable.

Second, if the disparity is large enough, the high-hashpower chain could launch 51% attacks against the weaker chain. Yet even with a 10:1 ETH/ETC hash ratio, such attacks did not occur. So this is not guaranteed. Still, miners favoring dominance over coexistence will always find ways to achieve it.

Next, consider strictly expanding hard forks (SEHFs). In SEHFs, the unforked chain remains valid under the forked rules. If the forked chain trades at a lower price than the original, its hash power value becomes lower, causing the unforked chain to eventually be accepted as the longest chain by both original and forked clients. Gradually, the forked chain gets "overwritten."

One argument holds that such forks have a strong inherent bias toward success because the forked chain risks being overwritten, lowering its market price and increasing overwrite likelihood. This argument resonates with me, making bilateral hard forks preferable over strictly expanding ones.

Many Bitcoin developers suggest manually creating a bilateral hard fork after a strictly expanding one to resolve this. But better yet is building bilateral incompatibility directly into the fork. For example, in Bitcoin, one could add rules that disable certain unused opcodes, then include transactions using those opcodes on the unforked chain—making it permanently invalid under forked rules. In Ethereum, almost all hard forks are automatically bilateral due to differences in state computation mechanics. Other blockchains will vary based on architecture.

The final fork type mentioned is user-activated soft forks (UASFs). In a UASF, users directly activate soft fork rules without requiring miner consensus; miners may be economically sidelined. If many users refuse to follow the UASF, the currency splits—resulting in a situation similar to a strictly expanding hard fork. Even though UASFs are technically optional, they leverage economic asymmetry to bias outcomes in their favor (though not absolutely—if a UASF is widely unpopular, it fails and causes chain splits).

However, UASFs are dangerous. Suppose project developers attempt a UASF patch converting a previously unrestricted opcode into one that only accepts transactions conforming to new rules—technically and politically controversial, and likely disliked by miners. Miners have a clever countermeasure: they can unilaterally implement a miner-activated soft fork (MASF), making any transaction using the new opcode always fail.

Now we have three rules:

- Original rule: opcode X is always valid.

- Soft fork rule: opcode X is valid only if other conditions meet new criteria.

- Miner-enforced rule: opcode X is always invalid.

Note that point 2 is a soft fork of point 1, and point 3 is a soft fork of point 2. Now, strong economic pressure exists on point 3, preventing the soft fork from achieving its intended goal.

Therefore, my conclusion is this: soft forks are a dangerous game, especially when contentious—once miners start pushing back, the situation becomes increasingly risky. Strictly expanding hard forks are also dangerous. Miner-activated soft forks are coercive; user-activated soft forks are less so, but still carry implicit coercion due to economic pressures, making them risky too. If you truly want to make a contentious change and believe the social cost is justified, do a clean, pure bilateral hard fork—take time to add replay protection—and let the invisible hand of the market sort it out.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News