From the 2008 Financial Crisis to Re-staking Markets: Liquidity Shortages and Leverage Risks Bring Potential "Subprime Crisis"

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

From the 2008 Financial Crisis to Re-staking Markets: Liquidity Shortages and Leverage Risks Bring Potential "Subprime Crisis"

When poor mortgage lending practices led to increased defaults, the resulting chain reaction of liquidations, panic, and liquidity shortages triggered a severe global economic downturn.

Author: Possibility Result

Translation: TechFlow

Introduction

As ETH staking yields have dropped to around 3%, investors are turning to a new instrument called Liquid Restaking Tokens (LRTs)—tokenized pools that re-stake ETH—to boost returns denominated in ETH. As a result, the value locked in LRTs has surged to $10 billion. A major driver of this trend is approximately $2.3 billion in collateral being used for leveraged positions. However, this strategy is not without risk. Each component within an LRT carries unique risks that are difficult to model, and on-chain liquidity remains insufficient to support effective liquidations during large-scale slashing events.

As Ethereum (ETH) staking yields fall to about 3%, investors are shifting toward tokenized restaking pools known as Liquid Restaking Tokens (LRTs) in search of higher ETH-denominated returns. Consequently, the value in LRTs has skyrocketed to $100 billion. This surge is largely driven by around $23 billion in collateral deployed into leveraged strategies. Yet, these gains come with significant risks. Individual positions within LRTs carry idiosyncratic risks that are hard to predict, and on-chain liquidity is inadequate to enable efficient liquidations during systemic de-leveraging events.

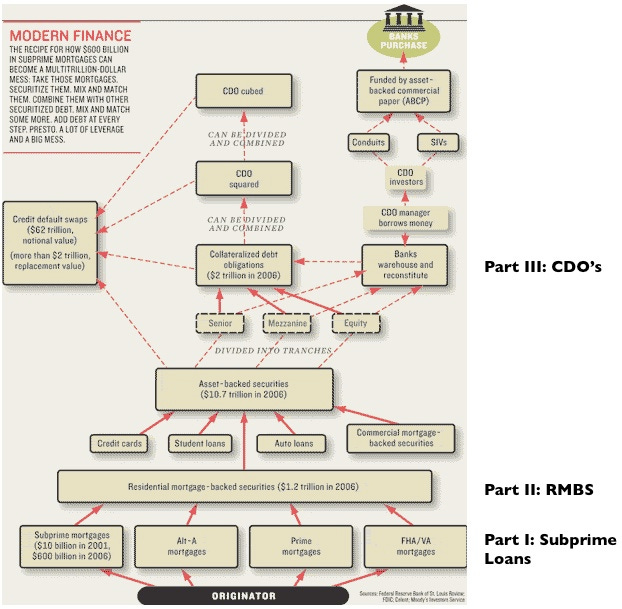

The current state of LRTs bears some resemblance to conditions preceding the 2008 financial crisis. In 2003, the federal funds rate fell to 1%, the lowest level in 50 years. To chase higher dollar returns, investors poured capital into the U.S. housing market. Since individual mortgages lacked liquidity, financial engineers bundled them into mortgage-backed securities (MBSs). At the core of the 2008 collapse were excessive leverage and the illiquidity of MBSs—securities that, like LRTs, contained complex and poorly understood idiosyncratic risks. When widespread mortgage defaults triggered cascading liquidations, panic, and a liquidity crunch, it led to a severe global economic recession.

Given these parallels, we should pause and ask: What lessons can we learn from history?

A Brief History of 2008

(Note: Much more could be said, but I focus only on elements most relevant to our narrative.)

A simplified story behind the 2008 recession:

Incentives for Loan Originators and Securitizers

Increased demand for mortgage-backed securities (MBSs) naturally incentivized greater supply of underlying mortgages. Thus, the “originate-and-distribute” model became increasingly popular. This allowed mortgage lenders (originators) to quickly offload default risk to securitizers, who then passed it on to traders seeking higher yields (distribution). By transferring risk, loan origination became more scalable—lenders could rapidly originate and sell mortgage debt without maintaining large balance sheets or robust risk management.

This introduces our first principal-agent problem: since originators did not bear the risk of the loans they issued, they had both the means and motivation to issue more mortgages with minimal personal risk. These misaligned incentives led to the emergence of notoriously bad loan products—some even described as “designed to default.”

Ratings Agencies’ Incentives

Beyond mortgage originators and securitizers, credit rating agencies played a crucial role in legitimizing these seemingly stable yield sources. Rating agencies assigned grades to each tranche of mortgage-backed securities (MBS), determining which were high quality (AAA) and which were risky (rated B or below). Their involvement accelerated the crisis in two key ways:

-

Ratings agencies were paid by the very institutions packaging and selling the MBSs. This conflict of interest led agencies to compete for business by lowering standards. For example, Fitch lost nearly all its MBS rating business because it was reluctant to award AAA ratings.

-

The risk models at the time were deeply flawed, particularly in assuming that mortgage defaults were independent events. As a result, securitizers could layer risk across tranches (e.g., the riskiest tranche absorbs the first X% of losses) to create collateralized debt obligations (CDOs). The safest tranches were often rated AAA, while the riskiest could be repackaged, re-tranched, and re-rated—sometimes with the top tier again receiving AAA ratings, despite the fact that default correlations were far from independent.

Excessive Leverage

In 1988, the Basel I Capital Accord was adopted, establishing capital requirements for internationally active banks. These requirements dictated how much capital a bank must hold per dollar of "risk-weighted" assets. Effectively, this capped banks' maximum leverage at 12.5:1. If you're familiar with crypto lending protocols, think of risk-weighted capital requirements as similar to Loan-to-Value (LTV) ratios for different assets. But “risk weighting” wasn’t always about reducing risk—it was sometimes used to encourage other goals. To promote housing finance, residential mortgage securities were assigned half the risk weight of commercial loans (50%), allowing banks to use double the leverage (25:1). By 2007, Basel II further reduced the risk weight for AAA-rated MBSs, enabling banks to leverage up to 62.5:1 (lower-rated MBSs had lower limits) (Government Accountability Office report on mortgage-related assets).

Despite capital rules, banks achieved “rating and regulatory arbitrage” through Structured Investment Vehicles (SIVs), bypassing additional leverage constraints. SIVs were legally independent entities “sponsored” by banks but maintained separate balance sheets. Though SIVs had little credit history, they could borrow at low rates due to market expectations that sponsoring banks would bail them out if losses occurred. In practice, banks and their off-balance-sheet SIVs operated as a single entity.

For years, banks faced no capital requirements for SIV debt. Only after Enron collapsed by hiding debt in complex off-balance-sheet vehicles did regulators take notice—but even then, substantive reform was lacking. SIVs were still required to meet only 10% of their sponsor bank’s capital requirements. In leverage terms, this meant banks could effectively apply 625:1 leverage on AAA-rated MBSs via SIVs. (Note: This doesn’t mean banks necessarily maximized leverage or held only MBSs—just that they had the capacity to do so.)

As a result, SIVs quickly became one of the primary funding channels for mortgages in the global financial system (Tooze 60).

Opacity Through Complexity

We also learn a critical lesson about complexity. Finance isn't simple—it relies on certain participants being better than others at assessing and bearing risk. Evaluating a government bond is relatively straightforward. A single mortgage is more complex but still manageable. But what about a pool of mortgages based on intricate assumptions? Or layered tranches built on further assumptions? Or multiple rounds of re-packaging and re-tranching? It becomes overwhelming.

In such complex structures, many participants outsourced risk assessment to “the market,” skipping detailed due diligence on derivatives.

There was strong profit incentive behind increasing complexity in derivatives markets—a complexity that favored sophisticated players over less experienced ones. When Fabrice “fabulous Fab” Tourre, a Goldman Sachs engineer, was asked who would buy their synthetic CDOs, he replied: “The widows and orphans of Belgium” (Blinder 78).

But the narrative of “Wall Street greed!” oversimplifies things. In fact, AAA-rated bonds issued between 2004 and 2007—the peak of market frenzy—performed quite well, suffering only 17 basis points in cumulative losses by 2011. Yet, the global market still collapsed. This suggests that excessive leverage and poor collateral may not have been the sole causes.

In “The Panic of 2007”, Gorton and Ordonez argue that when evaluating collateral quality is costly, even normal market fluctuations can trigger a recession. Their model shows that as markets go long periods without major shocks, lenders reduce spending on information acquisition. Over time, borrowers with low-quality, high-evaluation-cost collateral enter the market (e.g., subprime MBSs held in SIVs). Lower ratings reduce borrowing costs, boosting market activity as borrowers access cheaper financing. But when risky collateral values dip slightly, creditors may resume paying for evaluations. Suddenly, lenders avoid high-evaluation-cost collateral—even if quality is good. This credit contraction can severely depress market activity (Gorton and Ordonez).

Parallels Between MBS and LRT

Demand in the crypto market (especially Ethereum) for secure ETH yield mirrors traditional finance's pursuit of safe dollar returns. Just as U.S. Treasury yields declined in 2003, ETH staking yields have compressed as ~30% of ETH supply is now staked, pushing yields down to ~3%.

Similar to how declining MBS yields in 2008 pushed investors into riskier assets for higher returns, falling ETH staking yields are driving capital into riskier opportunities. This analogy isn’t new. In Alex Evans and Tarun Chitra’s article, “What PoS and DeFi Can Learn From Mortgage-Backed Securities,” they compare Liquid Staking Tokens (LSTs) to MBSs. The article explains how LSTs allow stakers to earn both staking rewards and DeFi yields without trade-offs. Since then, LST holders have primarily increased exposure via leverage—using their tokens as collateral for borrowing.

However, the relationship between MBS and Liquid Restaking Tokens (LRTs) appears even more complex.

While LSTs like stETH aggregate validators with relatively homogeneous risk (securing a stable protocol), restaking markets are fundamentally different. Restaking protocols enable simultaneous staking across diverse Active Validation Services (AVSs). These AVSs pay fees to stakers and operators to incentivize deposits. Unlike standard ETH staking, the number of restaking opportunities is virtually unlimited—but so are the potential unique risks (e.g., custom slashing conditions).

Attracted by higher yields, risk-seeking crypto investors have flocked to deposit capital. At the time of writing, total value locked (TVL) stands at ~$14 billion. Within this growth, Liquid Restaking Tokens (LRTs)—which represent shares in pooled restaking positions—account for a significant share (~$10 billion).

On one hand, standard ETH staking yields feel akin to “government-issued and backed” returns. Most stakers might assume that in the event of a catastrophic consensus failure causing mass slashing, Ethereum would hard fork to reverse losses.

On the other hand, restaking yields can come from any source. They cannot rely on ETH issuance to maintain security incentives. If flaws exist in custom slashing implementations, a hard fork to reverse losses would be far more contentious. If the situation is dire enough, we might see whether a hard fork following a restaking-related incident creates moral hazard—similar to bank bailouts deemed “too big to fail” to prevent systemic collapse.

The incentives for LRT issuers and ETH restakers mirror those of mortgage securitizers and banks chasing higher yields. As a result, we may not only see “loans designed to default” emerge in crypto—they may become widespread. One infamous type is the NINJA loan (No Income, No Job, No Assets). In restaking, this manifests as low-quality AVSs attracting massive LRT collateral to capture short-term inflationary token rewards. As we’ll discuss later, if this occurs at scale, it poses serious risks.

Real Risks

The most significant financial risk is a slashing event that causes LRT value to fall below liquidation thresholds across various lending protocols. Such an event would trigger cascading liquidations of LRTs, potentially impacting broader asset prices as restaked assets are unlocked and sold for stable assets. If the initial liquidation wave is large enough, it could spark chain reactions across other assets.

I can envision two plausible scenarios where this might occur:

-

Vulnerabilities in newly implemented slashing conditions. New protocols introduce new slashing rules, creating potential for novel exploits affecting many operators. If “designed-to-default” AVSs become widespread, such outcomes become highly likely. The scale of the slashing event matters too. Currently, AAVE (with ~$2.2 billion in LRT collateral at the time of writing) sets a 95% liquidation threshold for ETH borrowed against weETH (the most popular LRT). This means a slashing event impacting more than 5% of collateral would trigger the first wave of liquidations.

-

Social engineering attacks. An attacker—whether a protocol or operator—could convince various LRT platforms to allocate capital to their AVS. Then, they could establish a large short position (possibly including ETH and other derivatives). Since the capital isn’t theirs, their risk is limited to reputation. If the builder or operator doesn’t care about social standing (perhaps operating under pseudonymity) and the profits from the short position plus attack rewards are substantial, they stand to gain significantly.

Of course, all of this only becomes possible once slashing mechanisms are activated—which isn’t always the case. But until slashing is enabled, restaking provides minimal economic security benefits to protocols. Therefore, we must prepare for slashing risks.

Avoiding Past Mistakes

So the biggest question remains… What can we learn from the past?

Incentives Matter

Currently, competition among liquidity providers and LRT issuers centers on offering the highest ETH-denominated yields. Analogous to rising demand for high-risk mortgages, we will likely see growing demand for high-risk Active Validation Services (AVSs)—and this is where most slashing and liquidation risk lies. High-risk assets alone aren’t concerning; problems arise when they’re used in excessively leveraged positions with insufficient liquidity.

To limit excessive leverage, lending protocols set supply caps—maximum amounts of a given asset they accept as collateral. These caps heavily depend on available liquidity. With thin liquidity, liquidators struggle to convert seized collateral into stablecoins.

Just as banks took on excessive leverage to inflate portfolio valuations, lending protocols face strong incentives to violate best practices and enable more leverage. While we hope markets self-correct, history—like 2008—shows that when profit promises are high and information is costly, people tend to delegate or ignore due diligence.

Learning from past failures—such as rating agency incentives—suggests that creating an unbiased third party to assess and coordinate risks across collateral types and lending protocols would be highly beneficial, especially for Liquid Restaking Tokens (LRTs) and the protocols they secure. Such an entity could propose safe, industry-wide liquidation thresholds and supply cap guidelines. Deviations from these recommendations should be publicly disclosed for monitoring. Ideally, this organization should not be funded by parties benefiting from risky parameters, but by those seeking informed decisions. Perhaps it could be a crowdfunded initiative, an Ethereum Foundation grant, or a for-profit “come for the tool, stay for the network” project serving individual lenders and borrowers.

With support from the Ethereum Foundation, L2Beat has done excellent work managing a similar initiative for Layer 2s. So I’m hopeful something similar could succeed in restaking—indeed, Gauntlet (funded by the EigenLayer Foundation) seems to have started, though leverage data is currently missing. Even if such projects launch, eliminating risk entirely is unlikely—but they can at least reduce information acquisition costs for market participants.

This leads to a second related point.

Inadequate Modeling and Liquidity Shortages

We previously discussed how rating agencies and securitizers vastly overestimated the independence of mortgage defaults. The lesson? A housing downturn in one U.S. region could drastically affect prices elsewhere—not just nationally, but globally.

Why?

Because a small number of large institutions provided most of the world’s liquidity—and they also held MBSs. When poor lending practices caused MBS prices to fall, these institutions’ ability to provide market liquidity weakened. As assets had to be sold in illiquid markets to repay loans, prices everywhere—regardless of mortgage exposure—declined.

A similar overestimation of “shared” liquidity may unintentionally occur in lending protocol parameter design. Supply caps aim to ensure collateral can be liquidated without insolvency. But liquidity is a shared resource across protocols, essential for solvency during liquidations. If one protocol sets its cap based on current liquidity, and others follow independently, prior assumptions about available liquidity become inaccurate. Therefore, lending protocols should avoid making isolated decisions (unless they lack priority access to liquidity).

Unfortunately, if liquidity is permissionless for everyone at all times, protocols struggle to set safe parameters. However, granting priority access under certain conditions offers a solution. For instance, spot markets for collateral assets could implement hooks that, upon any trade, query lending protocols to check for ongoing liquidations. If a liquidation is in progress, the market would only allow asset sales triggered via message calls from the lending protocol itself. This feature would allow lending protocols to set supply caps with greater confidence through cooperation with exchanges.

Case Study:

We may already have a real-world case study to observe LRT market dynamics.

AAVE holds over $2.2 billion in weETH collateral, yet according to Gauntlet’s dashboard, on-chain liquidity for exiting to wstETH, wETH, or rETH is only $37 million (not accounting for slippage or USDC exits, making actual liquidity worse).

As other lending protocols begin accepting weETH (e.g., Spark, with over $150 million in weETH TVL), competition for this limited liquidity will intensify.

The liquidation threshold for ETH borrowed against weETH is 95%, meaning a slashing event affecting more than 5% of LRT collateral could trigger the first wave of liquidations. Billions in sell pressure would flood the market. This would almost certainly drive down wstETH and ETH prices as liquidators convert assets to USDC, risking follow-on liquidations across ETH and related assets. But as previously noted, as long as no liquidation occurs, risk remains low. Thus, deposits in AAVE and other lending protocols remain safe—for now.

Key Differences

It would be incomplete to write about similarities between LRTs and MBSs—or draw parallels between today’s crypto and pre-2008 finance—without discussing key differences. While this article highlights important parallels, clear distinctions exist.

One of the most important differences lies in the nature of leverage: on-chain leverage is open, overcollateralized, algorithmically enforced, and transparent, versus the opaque, undercollateralized, and discretionary leverage of banks and shadow banks. Overcollateralization, though capital inefficient, brings key advantages. For instance, if a borrower defaults (and sufficient liquidity exists), lenders should always expect full repayment—unlike undercollateralized loans. The open, algorithmic nature enables immediate liquidation and allows anyone to participate. Thus, untrusted custodians or malicious counterparties cannot engage in harmful actions like delaying liquidations, executing fire sales below fair value, or rehypothecating collateral without consent.

Transparency is a major advantage. On-chain data about protocol balances and collateral quality is verifiable by anyone. In the context of Gorton and Ordonez’s research, we can say DeFi operates in an environment where assessing collateral quality is less costly. Therefore, revealing collateral quality information should be cheaper, enabling markets to adjust more frequently and at lower cost. In practice, this gives lenders and users richer information for decision-making on key parameters. That said, for restaking, some subjective off-chain factors—like code quality and team background—remain expensive to evaluate.

An anecdotal sign: since the collapses of BlockFi, Celsius, and others, on-chain lending activity appears to have increased. Notably, we’ve seen significant growth in deposits on AAVE and Morpho, with little evidence of off-chain lending operations reaching previous cycle levels. However, obtaining precise data on the current size of off-chain lending is difficult—meaning there may be significant but underreported growth. Unless a direct lending protocol hack occurs, all else equal, on-chain leverage should be more resilient due to the reasons above.

As the slashing risk for LRTs increases, we may soon witness a real test of the strengths and weaknesses of transparent, overcollateralized, open, and algorithm-driven lending. Finally, perhaps the greatest difference is this: if disaster strikes, there will be no government to bail us out. No state backing for lenders, no Keynesian tokenomics. Only code, its state, and how that state changes. Therefore, we must strive to avoid unnecessary mistakes.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News