Covenants: The Programmability of Bitcoin

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

Covenants: The Programmability of Bitcoin

What Exactly Are Bitcoin's "Limiting Conditions"?

Author: Jeffrey HU, Head of Investment Research at HashKey Capital, and Harper LI, Investment Manager at HashKey Capital

Recently, a wave of discussion has emerged within the Bitcoin community regarding the re-enabling of opcodes such as OP_CAT. Taproot Wizard has attracted significant attention by launching Quantum Cats NFTs and claiming to have secured BIP-420 designation. Supporters argue that enabling OP_CAT could unlock “covenants” on Bitcoin, thereby introducing smart contract-like functionality or programmability.

If you notice the term "covenants" and do a quick search, you’ll quickly find yourself down a deep rabbit hole. Developers have been discussing this for years—beyond OP_CAT, there are various proposed mechanisms like OP_CTV, APO, OP_VAULT, and others aimed at achieving covenants.

So what exactly are Bitcoin covenants? Why have they drawn so much sustained interest from developers over the years? What new programmable capabilities could they enable on Bitcoin, and how do they work under the hood? This article aims to provide a broad overview and discussion.

What Are Covenants?

Covenants—translated into Chinese as “限制条款” (restriction clauses), sometimes also called “contracts”—are mechanisms that allow conditions to be imposed on future Bitcoin transactions.

Bitcoin’s current scripting system already includes some restrictions—for example, requiring valid signatures or matching redemption scripts when spending. However, once unlocked, users can spend the UTXO to any destination of their choosing.

Covenants go further: in addition to unlocking conditions, they impose additional constraints—such as restricting how a UTXO may be spent in the future (enabling “earmarked funds”), or placing conditions on other inputs within the same transaction.

More precisely, Bitcoin scripts today already support limited forms of covenants. For instance, time-locks using opcodes introspect fields like nLockTime or nSequence to restrict when a transaction can be spent—but these are largely confined to temporal limitations.

Why then do researchers and developers want to build more sophisticated covenant checks? Because covenants aren’t about restriction for its own sake—they establish rules for transaction execution. This ensures users can only act according to predefined logic, enabling complex application workflows.

Paradoxically, imposing constraints actually unlocks more use cases.

Use Cases

Enforcing Staking Penalties

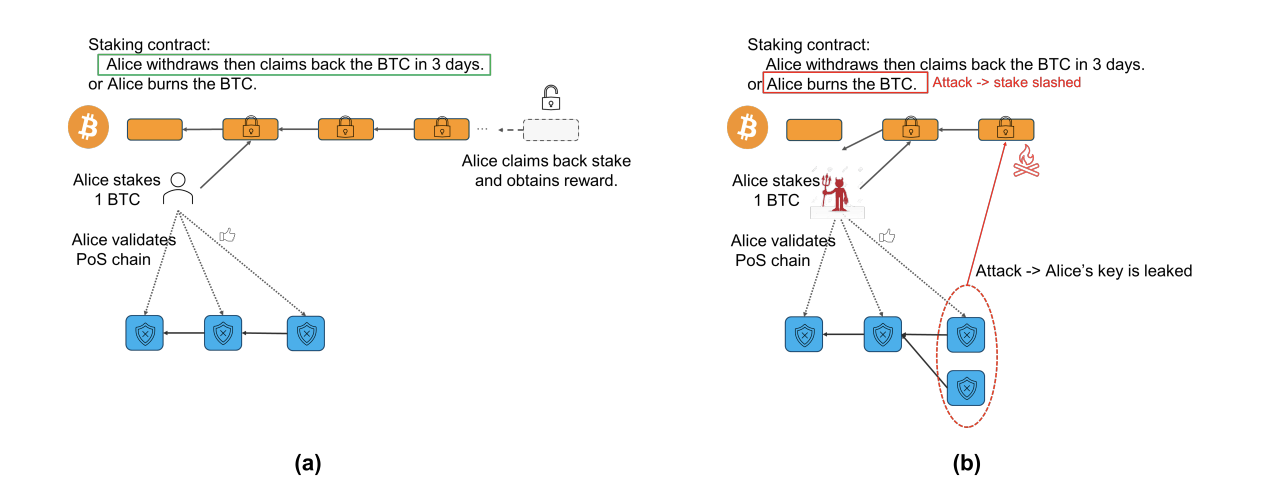

One intuitive example of covenants is Babylon’s slashing mechanism in Bitcoin staking.

In Babylon’s Bitcoin staking process, users send their BTC to a special script on-chain with two spending paths:

-

Happy ending: After a certain period, the user can reclaim their funds with a standard signature—this completes the unstake process

-

Bad ending: If the user commits malicious acts (e.g., double-signing) on a PoS chain secured via Babylon, an Extractable One-Time Signature (EOTS) allows network actors to unlock those funds and forcibly send part of them to a burn address (i.e., slash)

Source: Bitcoin Staking: Unlocking 21M Bitcoins to Secure the Proof-of-Stake Economy

Note the word “forcibly.” Even if the malicious party knows the private key, they cannot redirect the funds elsewhere—the assets must be burned. This prevents attackers from front-running the slashing by moving funds before punishment occurs.

With OP_CTV or similar covenants enabled, this forced transfer could be directly enforced through opcode logic in the staking script’s bad-ending branch.

Before OP_CTV activation, Babylon must rely onworkarounds, simulating covenant enforcement via joint execution between users and a committee.

Congestion Control

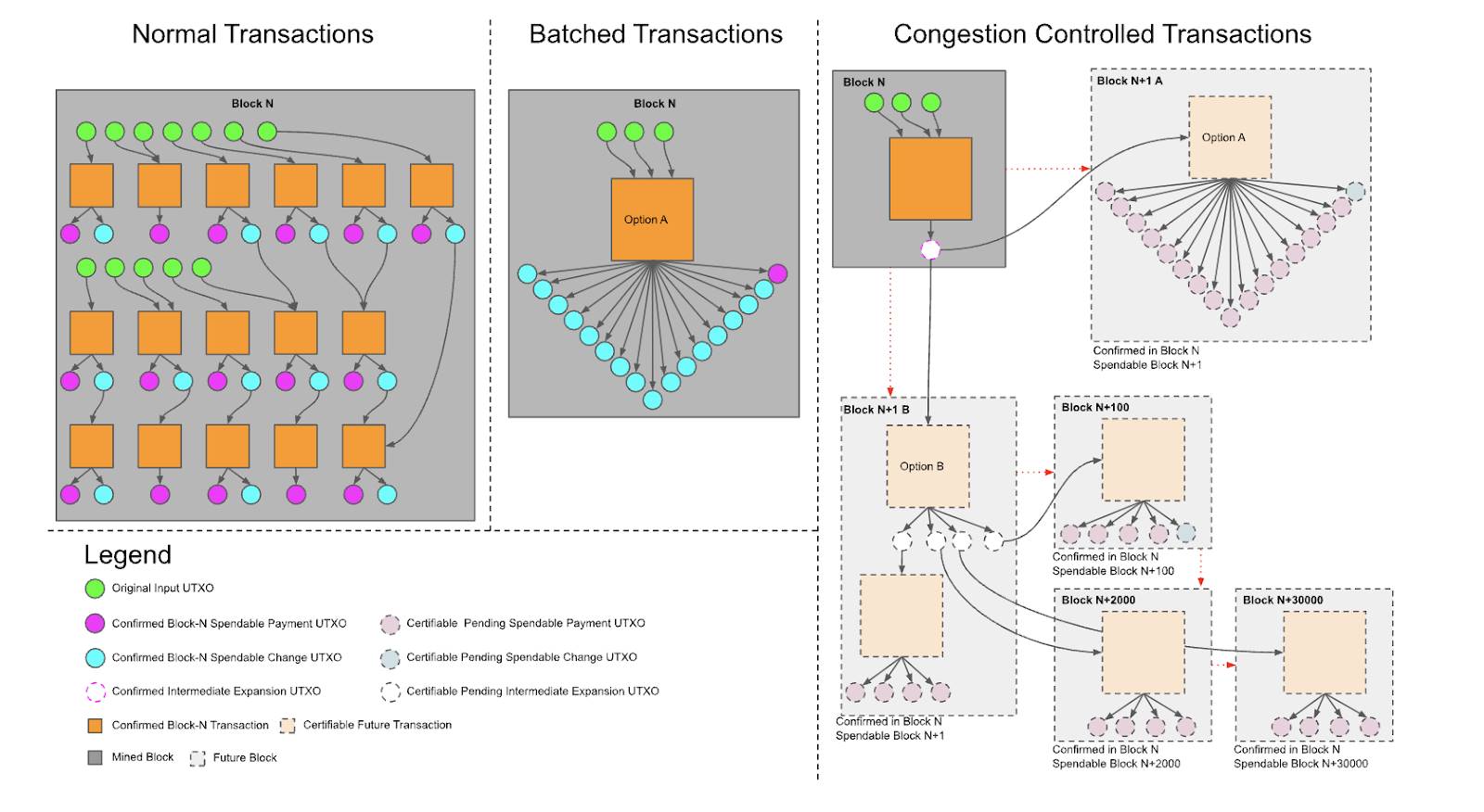

Typically, congestion refers to high fee rates on the Bitcoin network, where many transactions queue in the mempool. To get fast confirmations, users must pay higher fees.

When a user needs to send multiple payments during peak times, costs rise significantly—and their actions further push up overall network fees.

With covenants, one solution is for the sender to commit to a batched transaction upfront. Recipients can trust that final settlement will occur and simply wait until fees drop before claiming their portion.

As shown below, when demand for block space is high, transactions become expensive. Using OP_CHECKTEMPLATEVERIFY (OP_CTV), large payment processors can aggregate all payments into a single O(1) transaction for confirmation. Later, when block space demand decreases, individual payouts can be expanded from that UTXO.

Source: https://utxos.org/uses/scaling/

This is one of the most well-known applications motivating OP_CTV. Many more examples—including Soft Fork Bets, Decentralized Options, Drivechains, Batch Channels, Non-Interactive Channels, Trustless Coordination-Free Mining Pools, Vaults, and Safer HTLCs—can be found at https://utxos.org/uses/.

Vaults

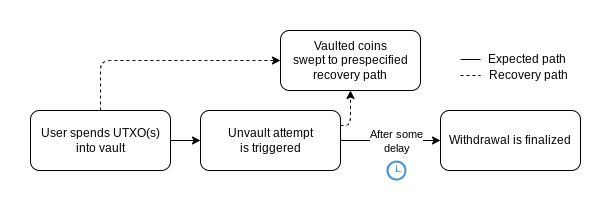

Vaults are widely discussed in Bitcoin circles, especially in the context of covenants. Since everyday usage requires balancing security and accessibility, people desire vault-like applications that protect funds—even if private keys are compromised.

With covenant-enabling technologies, building such vaults becomes far easier.

Take the OP_VAULT proposal: to withdraw from a vault, a user first broadcasts a “trigger” transaction indicating intent to spend, which sets up the following rules:

-

If everything is normal, a second withdrawal transaction can be broadcast after N blocks, allowing full control over the funds

-

If the trigger was issued under coercion (e.g., physical threat) or theft, the owner can intervene within N blocks and redirect funds to a secure backup address

OP_VAULT workflow, Source: BIP-345

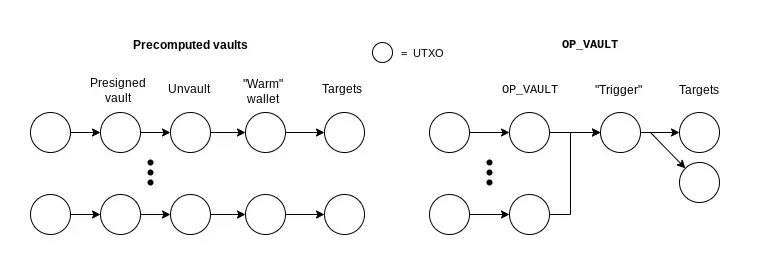

Note that vaults can be built without covenants—for example, by pre-signing future transactions and destroying the private key. But this approach has major drawbacks: it requires trusted setup (ensuring the key is truly destroyed), fixed amounts and fees (due to pre-signing), and lacks flexibility.

Comparison between OP_VAULT and pre-signed vaults, Source: BIP-345

More Robust and Flexible State Channels

State channels—including Lightning Network—are generally considered to offer near-on-chain security, assuming participants monitor the latest state and can timely publish updates. With covenants, however, new designs can make these systems even more robust or flexible. Notable examples include Eltoo and Ark.

Eltoo (also known as LN-Symmetry) is a prime example. Named phonetically after “L2,” it proposes a layer-2 execution model where newer channel states automatically override older ones—eliminating the need for penalty mechanisms and removing the requirement to store past states to prevent cheating. Eltoo relies on a signature scheme called SIGHASH_NOINPUT, formalized as APO (BIP-118).

Ark aims to reduce inbound liquidity and channel management burdens in Lightning. It operates as a joinpool protocol where multiple users interact off-chain via virtual UTXOs (vUTXOs) with a service provider, sharing a single on-chain UTXO to cut costs. While Ark can be implemented today, covenants would allow it to reduce interactivity and enable trust-minimized unilateral exits using transaction templates.

Overview of Covenant Technologies

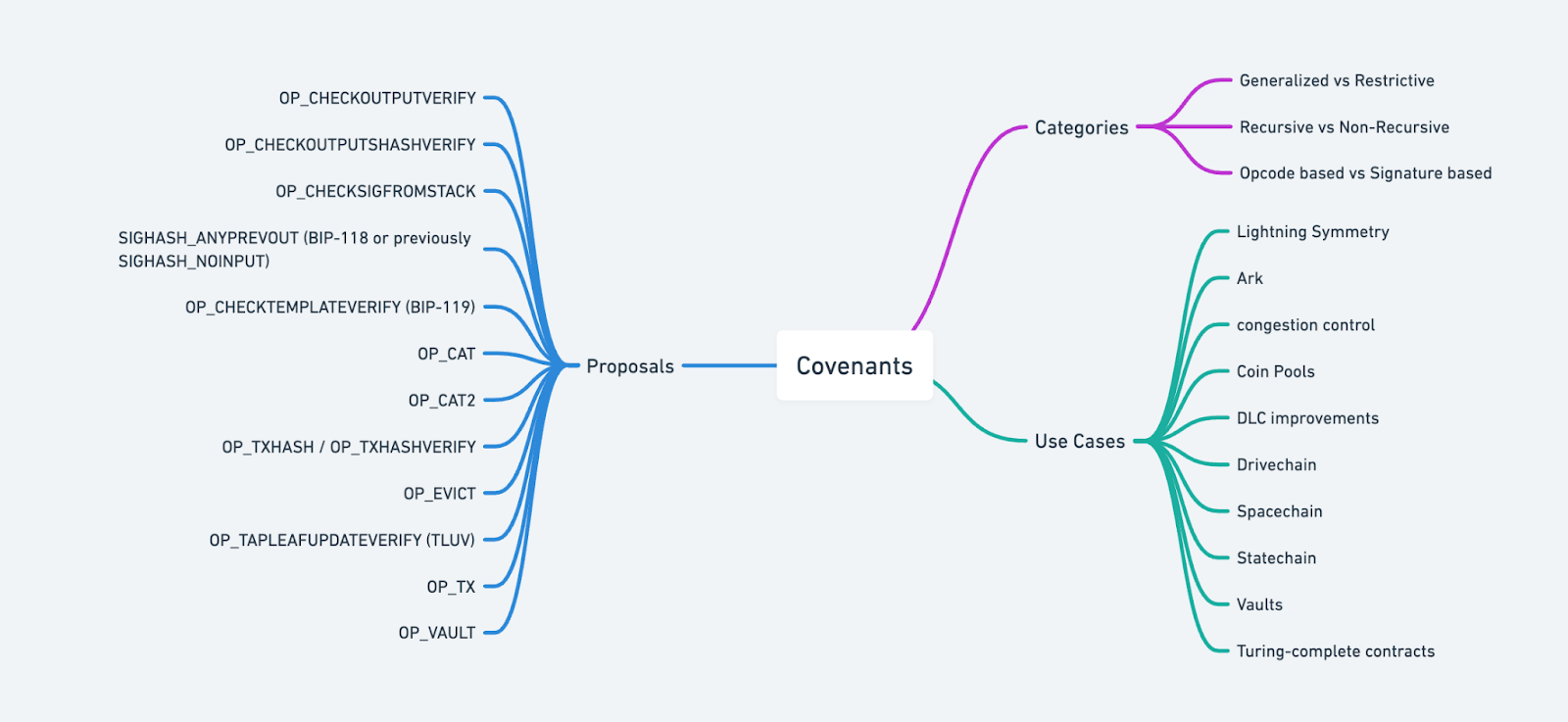

From the above use cases, it’s clear that covenants describe a capability rather than a specific technology—there are multiple ways to achieve them. They can be categorized along several dimensions:

-

Type: General-purpose vs. Special-purpose

-

Implementation: Opcode-based vs. Signature-based

-

Recursion: Recursive vs. Non-recursive

Recursion refers to whether a covenant can constrain not just the next spend, but subsequent spends beyond that—allowing restrictions to propagate across multiple transaction layers.

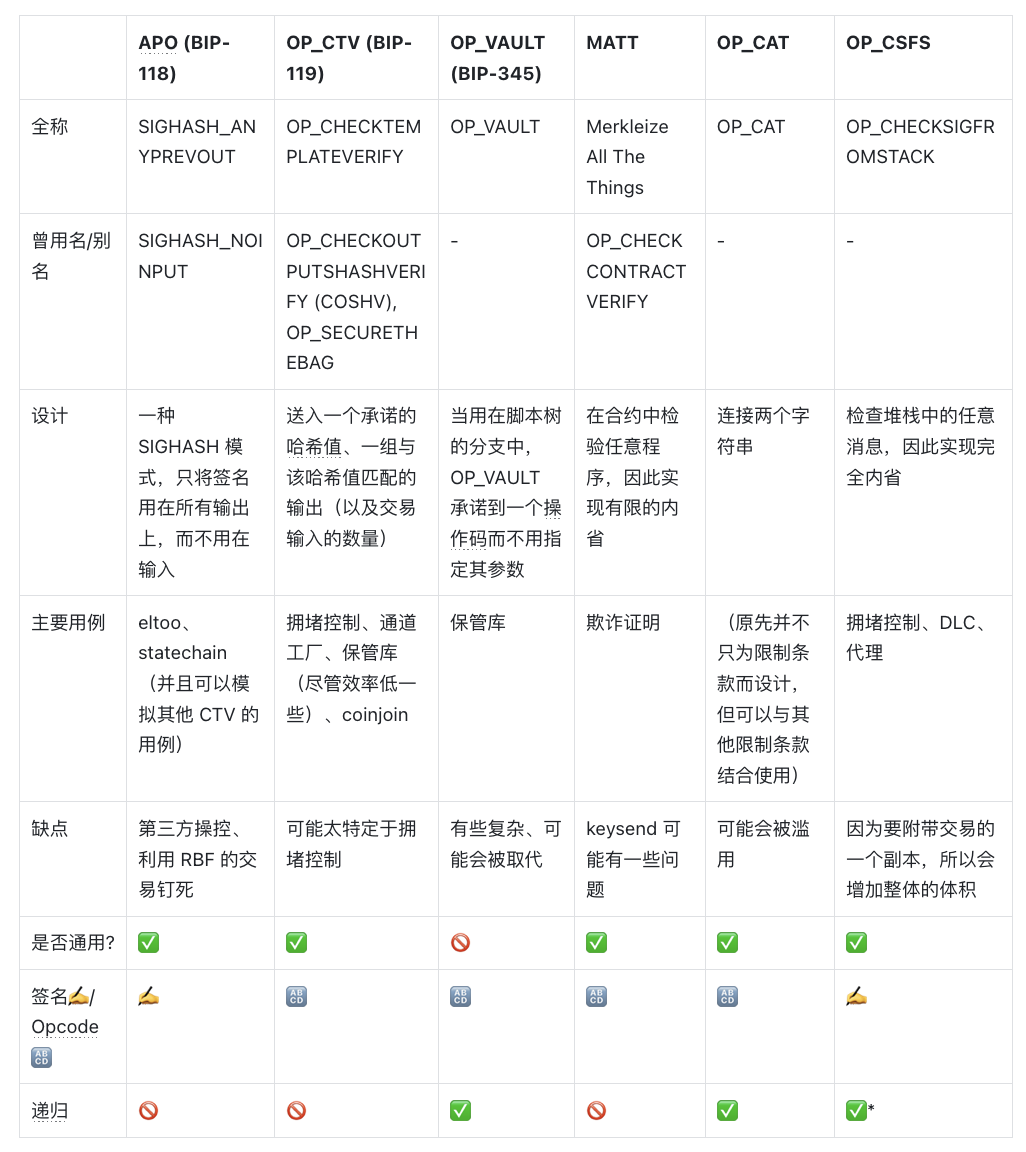

Some prominent covenant proposals include:

*Recursive: when combined with OP_CAT

Design Principles Behind Covenants

As introduced earlier, Bitcoin scripts today mainly restrict unlocking conditions but say nothing about how a UTXO may be spent afterward. To implement covenants, we must ask: why can’t current Bitcoin scripts enforce such restrictions?

The core issue is that Bitcoin scripts currently cannot read the content of the transaction itself—this lack of introspection limits expressiveness.

If scripts could introspect transaction data—including outputs—we could enforce arbitrary spending rules, thus achieving covenants.

Accordingly, most covenant designs focus on enabling introspection.

Opcode-Based vs. Signature-Based Approaches

The most direct approach is adding one or more opcodes that allow scripts to directly read transaction data. This is the opcode-based path.

An alternative is avoiding direct introspection altogether. Instead, leverage the hash of transaction contents: if a signature commits to this hash, modifying OP_CHECKSIG-like opcodes to verify such commitments indirectly enables introspection. This is the signature-based route, including APO and OP_CSFS.

APO

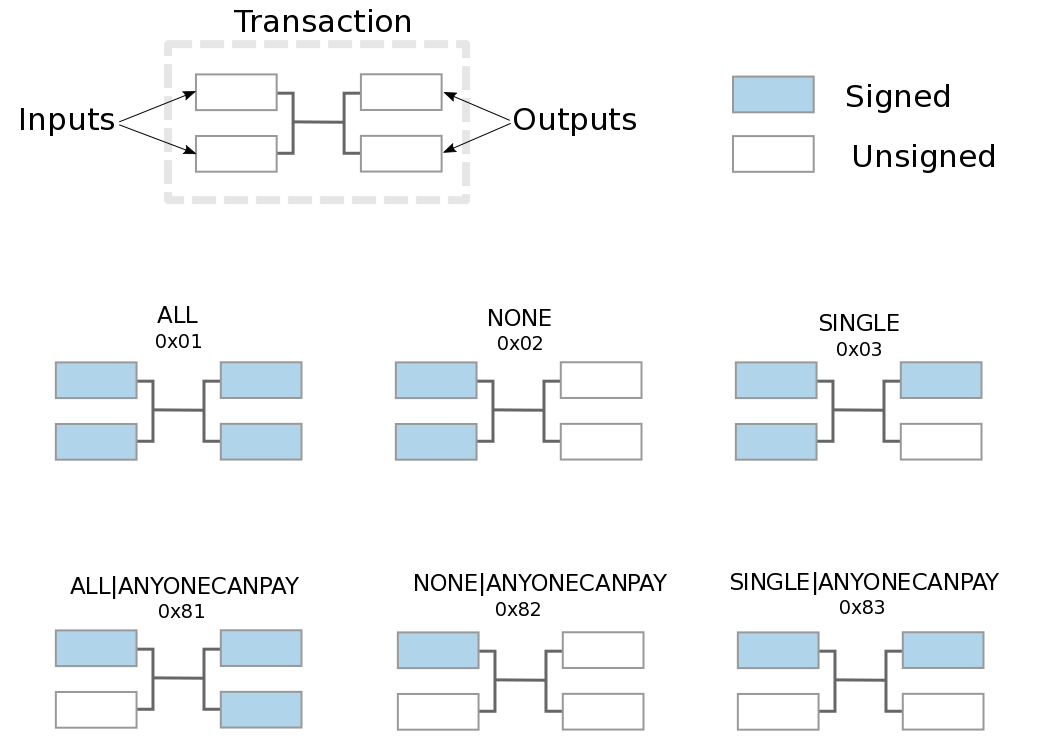

SIGHASH_ANYPREVOUT (APO) is a proposed Bitcoin signature scheme. The simplest way to sign a transaction is to commit to all inputs and outputs. But Bitcoin supports more flexible modes via SIGHASH flags, selectively committing to parts of a transaction.

Current SIGHASH modes and their scope (Source: Mastering Bitcoin, 2nd Edition)

As shown, ALL signs all inputs and outputs; NONE signs inputs only, leaving outputs unrestricted; SINGLE applies only to the output with the same index. These can be combined—for instance, ANYONECANPAY modifies behavior to apply only to one input.

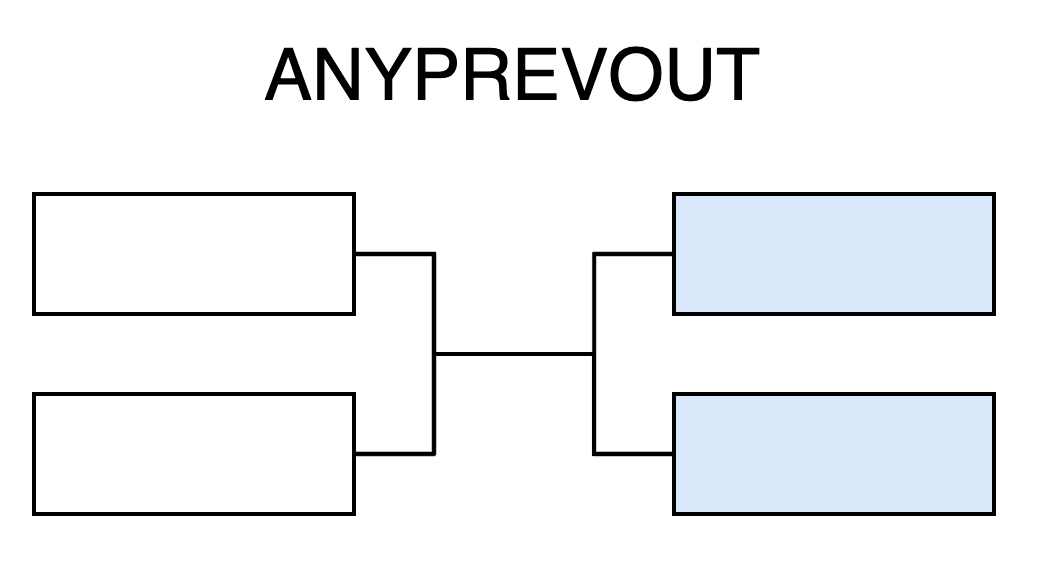

APO introduces a mode that signs only the outputs, not the inputs. This means a transaction signed with APO can later be attached to any qualifying UTXO as input.

This flexibility forms the theoretical foundation of APO-based covenants:

-

Pre-create one or more spending transactions

-

Derive a public key from these transactions’ data that yields exactly one valid signature

-

Any funds sent to this address can only be spent via the pre-defined transactions

Crucially, since no private key corresponds to this public key, funds are locked into the predetermined spending paths. Thus, by defining the outputs in advance, we enforce covenant-like behavior.

We can draw a parallel to Ethereum smart contracts: both restrict withdrawals to predefined conditions rather than arbitrary EOA-controlled spending. In this sense, Bitcoin can achieve contract-like behavior purely through signature enhancements.

However, a challenge arises due to circular dependencies: pre-signing requires knowing input details, which are unknown until the transaction is created.

APO and SIGHASH_NOINPUT solve this by decoupling input commitment—only the outputs need to be known at signing time.

OP_CTV

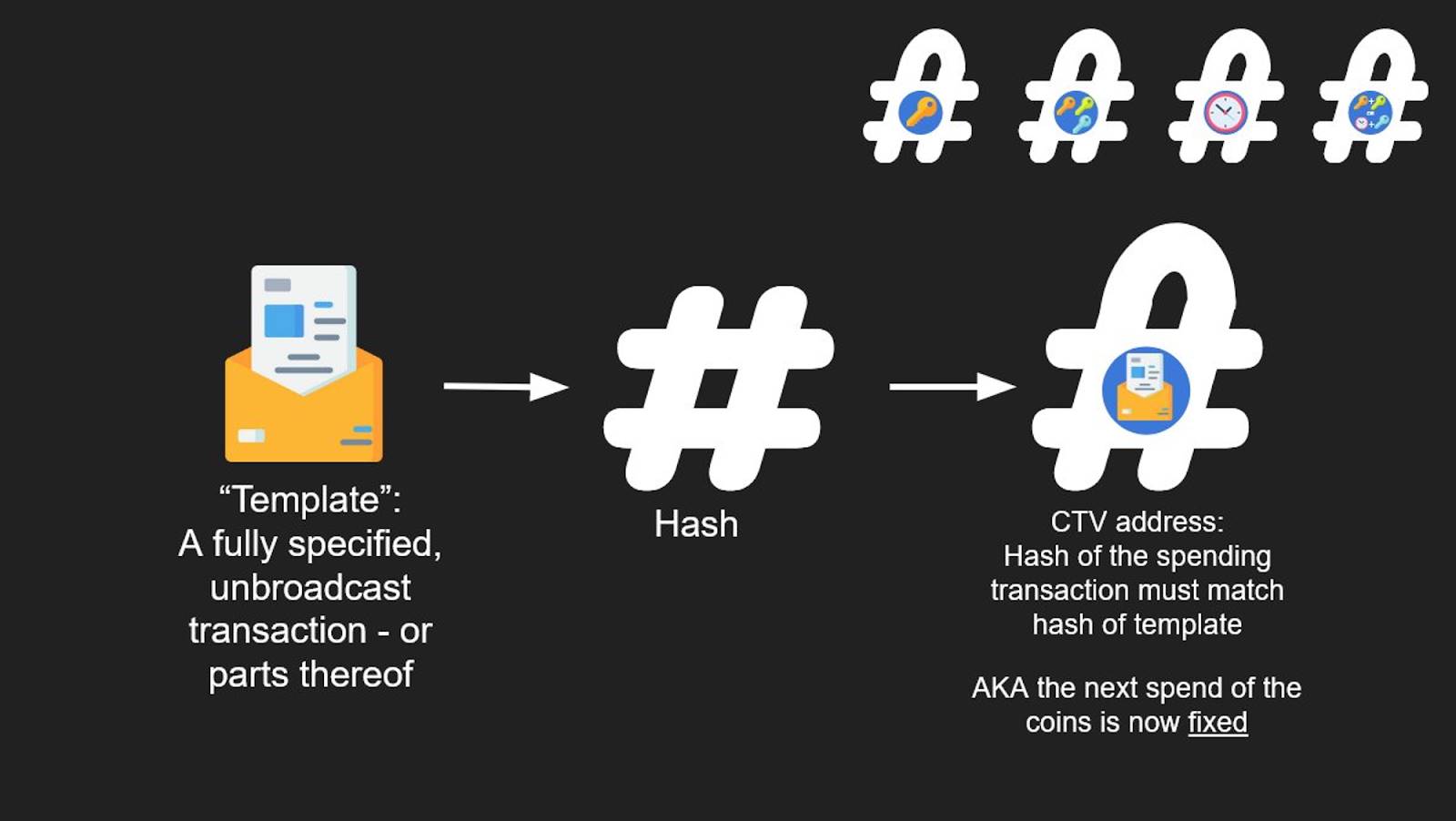

OP_CHECKTEMPLATEVERIFY (CTV), or BIP-119, takes an opcode-based approach. It accepts a commitment hash as a parameter and requires that any transaction executing the opcode contain outputs matching that commitment. CTV allows Bitcoin users to constrain how their bitcoins are spent.

Originally proposed as OP_CHECKOUTPUTSHASHVERIFY (COSHV), early criticism focused on its narrow focus on congestion control, lacking generality.

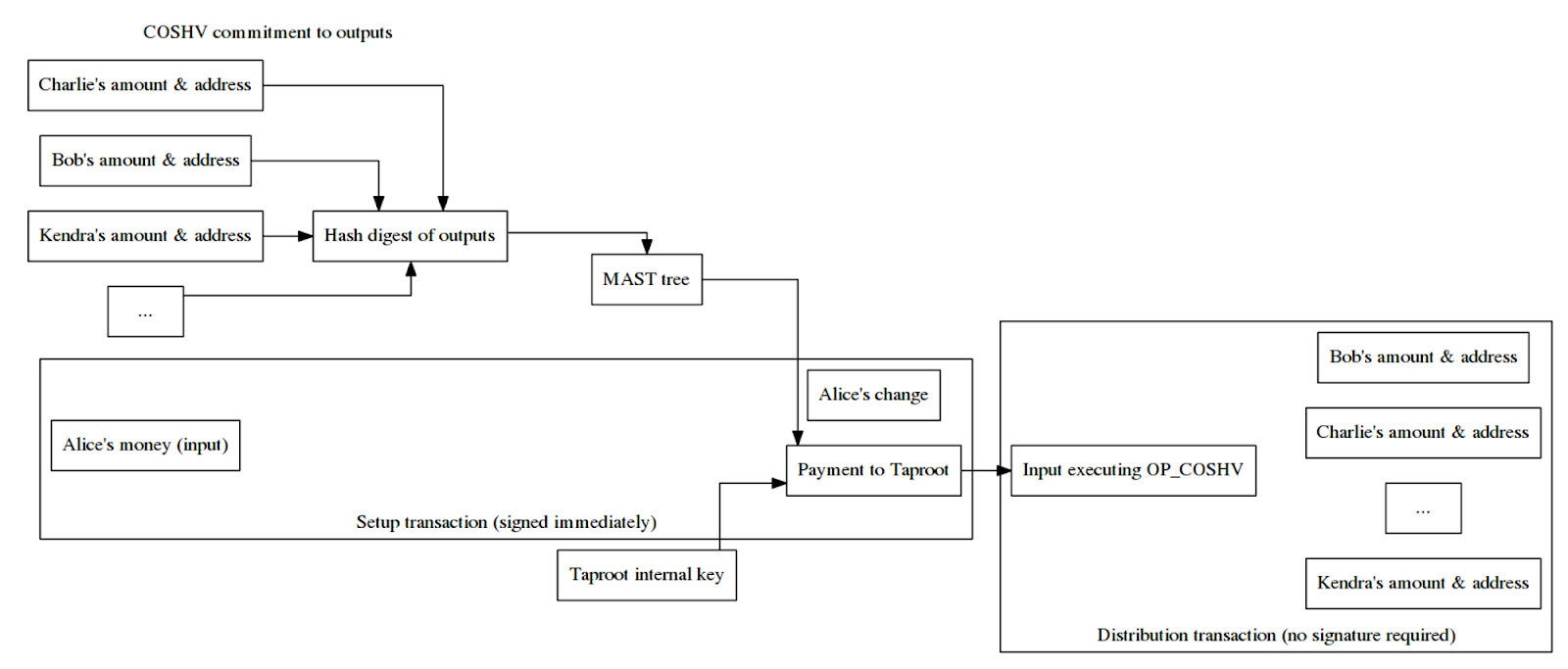

In the congestion control example, Alice creates 10 outputs, hashes them, and uses the digest to construct a tapleaf script containing COSHV. She also uses participants’ public keys to form the internal key of a Taproot address, enabling cooperative spending without revealing script paths.

Alice then distributes copies of the 10 outputs to each recipient via asynchronous channels (e.g., email or cloud storage), so they can independently verify her setup transaction. Later, any participant can create a spending transaction containing the committed outputs.

Critically, recipients don’t need to be online or interact during setup.

Source:

https://bitcoinops.org/en/newsletters/2019/05/29/#proposed-transaction-output-commitments

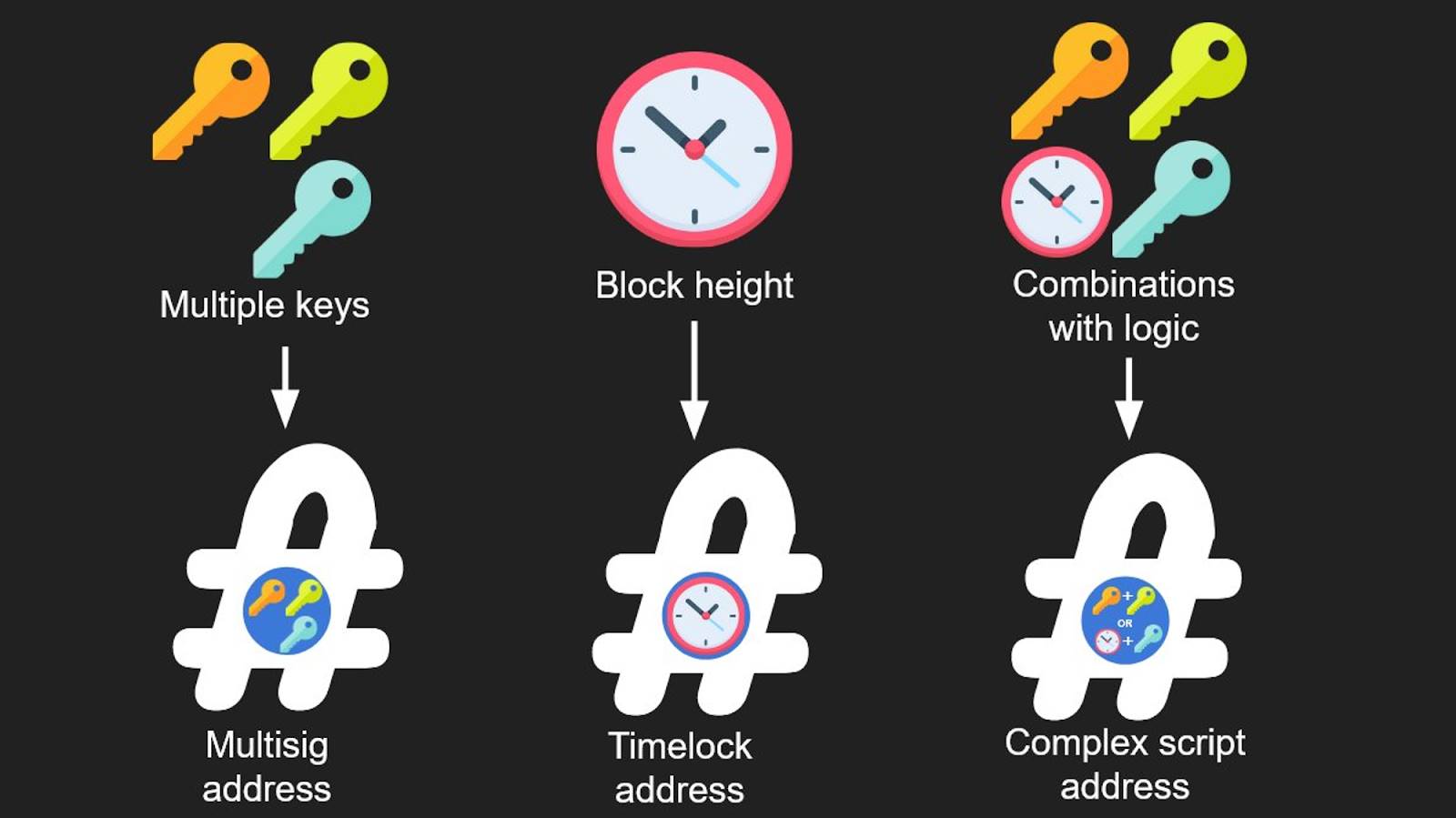

Like APO, addresses can be constructed based on spending conditions, supporting various locking patterns: multi-key setups, timelocks, logical combinations.

Source:

https://twitter.com/OwenKemeys/status/1741575353716326835

CTV essentially verifies whether a spending transaction’s hash matches the expected template—using transaction data as the “key” to unlock funds.

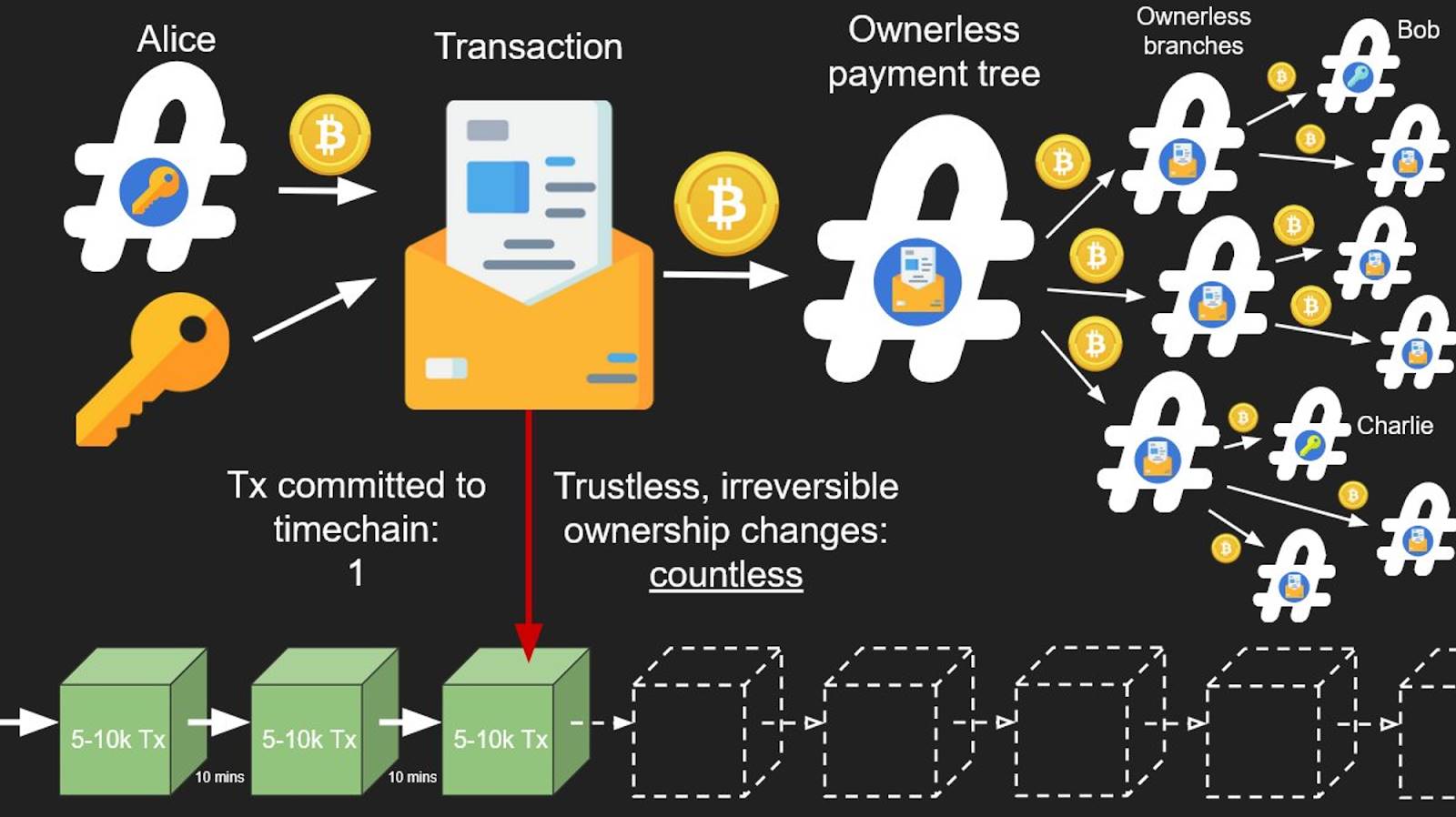

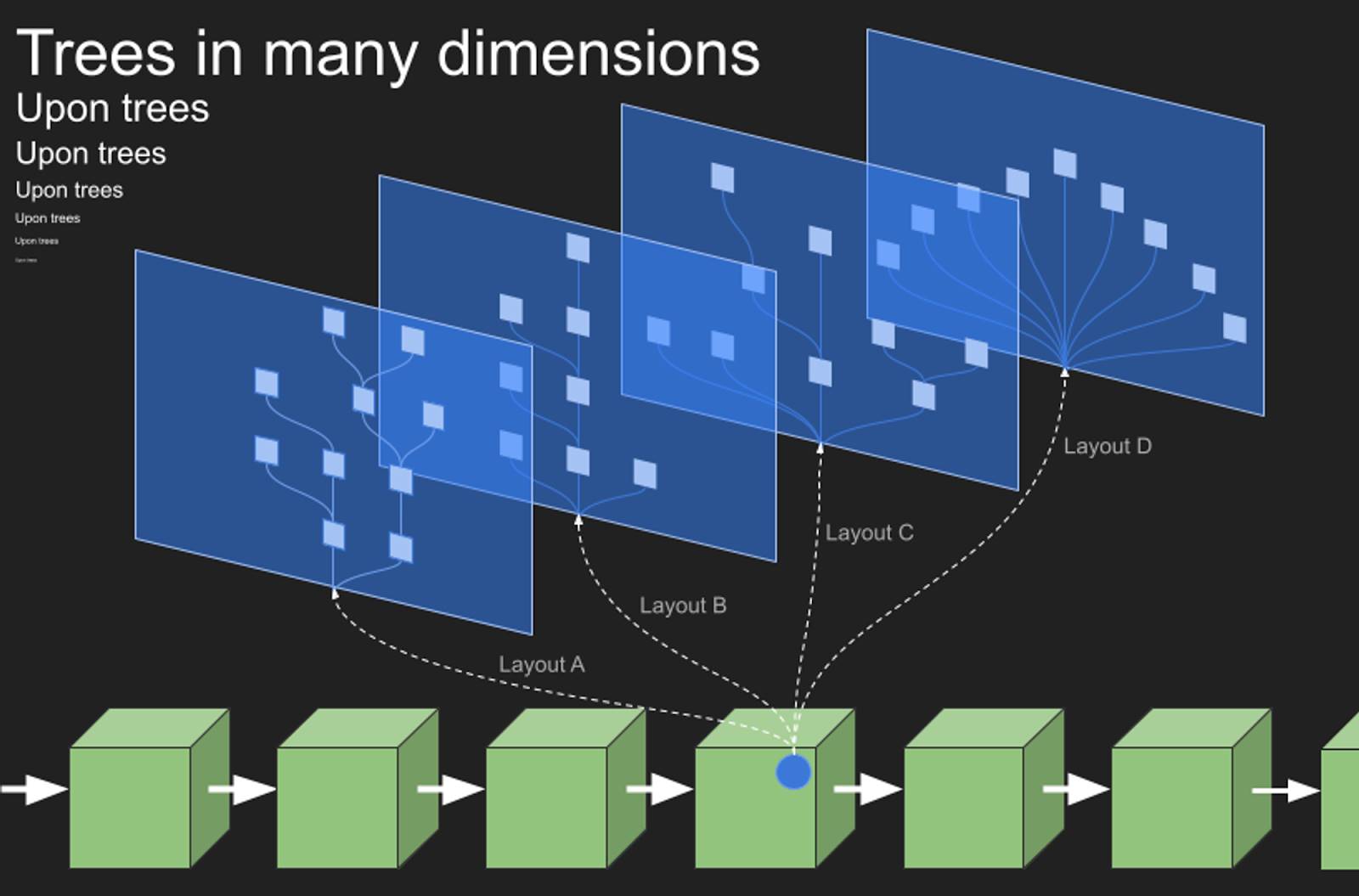

Extending the earlier example: recipients can forward their rights via pre-signed, un-broadcast transactions to new parties, forming a tree structure. With just one UTXO on-chain, Alice can orchestrate balance changes across many users.

Source:

https://twitter.com/OwenKemeys/status/1741575353716326835

What if some leaves represent Lightning channels, cold storage, or alternative payment routes? The tree evolves from a simple spending hierarchy into a multidimensional, multilayered framework—unlocking richer, more flexible applications.

Source:

https://twitter.com/OwenKemeys/status/1744181234417140076

Since its proposal, CTV has evolved—from COSHV in 2019, assigned BIP-119 in 2020, inspired Sapio (a language for CTV contracts), and sparked extensive community debate in 2022–2023 over activation strategies. It remains one of the most actively discussed soft fork upgrade proposals.

OP_CAT

As introduced at the beginning, OP_CAT is another highly watched upgrade proposal—it concatenates two stack elements. Though seemingly simple, OP_CAT enables powerful scripting capabilities.

A direct application is Merkle tree operations. A Merkle node combines two elements, then hashes them. Since Bitcoin scripts already have OP_SHA256, enabling OP_CAT would allow full Merkle proofs in-script—granting lightweight clients better verification abilities.

Another foundational use is enhancing Schnorr signatures: by committing to both a public key and a public nonce via concatenation, attempting to reuse the nonce in another transaction would leak the private key. Thus, OP_CAT enables nonce commitment, securing signed transactions.

Other applications of OP_CAT include: Bistream, Tree Signatures, Quantum-resistant Lamport Signatures, and vaults.

OP_CAT isn’t new—it existed in Bitcoin’s earliest versions but was disabled in 2010 due to potential exploit risks. For example, repeated use of OP_DUP and OP_CAT could cause stack overflow attacks on full nodes—see this demo.

Would re-enabling OP_CAT reintroduce stack explosion risks? No—current proposals limit OP_CAT to Tapscript, which caps stack element size at 520 bytes, preventing prior vulnerabilities. Some argue Satoshi’s removal was overly cautious. Yet due to OP_CAT’s flexibility, undiscovered attack vectors may still exist.

Given its utility and manageable risk profile, OP_CAT has recently gained strong momentum, undergoing PR review, and stands among the hottest upgrade proposals today.

Conclusion

“Discipline equals freedom.” As shown, covenants allow Bitcoin scripts to restrict how UTXOs are spent in the future, enabling smart contract-like transaction logic. Compared to off-chain approaches like BitVM, this programming model is more native to Bitcoin, verifiable directly on-chain, and enhances both on-chain applications (e.g., congestion control), off-chain systems (e.g., state channels), and new directions (e.g., staking penalties).

Combining covenant techniques with low-level upgrades could further unlock programmability. For example, the recently reviewed 64-bit arithmetic operator proposal could integrate with OP_TLUV or other covenants to enable value-aware scripting based on satoshi amounts in outputs.

However, covenants may also introduce unintended abuses or vulnerabilities, so the community remains cautious. Moreover, covenant upgrades require consensus-level soft forks. Given the complexity seen during Taproot’s rollout, covenant adoption will likely take time.

Special Thanks

Thanks to Ajian, Fisher, and Ben for reviewing and providing feedback on this article!

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News