Flashbots, MEV, and Incentive Reengineering: The Quest to Build Decentralized Financial Systems

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

Flashbots, MEV, and Incentive Reengineering: The Quest to Build Decentralized Financial Systems

Maintaining the health of decentralized systems always requires continuous, strenuous effort—constantly playing a game of whack-a-mole. Trust propagation in decentralized systems demands the distribution of responsibility and vigilance, especially given the vast economic incentives at stake: for better or worse, MEV is here to stay.

Author: 0xFishylosopher

Translation: TechFlow

*Note: This article originally comes from the Stanford Blockchain Review. TechFlow is an official partner of the Stanford Blockchain Review and has been exclusively authorized to translate and republish this content.

Introduction

MEV, or Maximum Extractable Value, is a byproduct of blockchain design and a unique phenomenon in DeFi.

At its core, MEV is simply an instance of profit-maximizing behavior—blockchain validators seeking to maximize profits from their transaction validation duties. While one might argue that MEV can be beneficial by improving capital efficiency, it significantly impacts user experience in decentralized applications, including higher gas fees, slippage, and risks such as validator collusion and centralization.

In this article, 0xFishylosopher will first explore MEV as a theoretical concept and the systemic risks it poses to the ecosystem. Following that, using Flashbots as a case study, we will examine how the DeFi community has attempted to mitigate these negative externalities of MEV.

The "Flash Boys" Club

MEV is a feature of blockchain technology, not a bug. In any given blockchain network, validators (or miners in the traditional Proof-of-Work model) decide which data gets included on-chain. Specifically, they control the order of transactions on-chain. It turns out that certain transaction sequences offer validators significant profits. Therefore, as rational economic agents, validators will arrange transactions in ways that maximize their revenue.

The concept of MEV was first detailed by smart contract researcher Phil Daian in a seminal paper titled "Flash Boys 2.0," where researchers highlighted the existence of numerous bots and arbitrage agents attempting to "predict and exploit" ordinary users' DEX trades—similar to how high-frequency traders in traditional finance aggressively optimize for latency. To illustrate the scale of this phenomenon, within just the past 24 hours at the time of writing, MEV operations have generated 2,578 ETH—approximately $4.9 million at current prices.

Although MEV is a broad term encompassing many different arbitrage methods and scenarios, several key characteristics underpin much of the MEV opportunities in DeFi. First, much MEV is achieved through a process known as "Priority Gas Auctions" (PGA), where users pay higher transaction (gas) fees to get their transactions executed earlier. Since many arbitrage bots rely on front-running trades to generate profits, these bots engage in bidding wars, continuously increasing gas prices to ensure their transactions are prioritized by validators—leading to severe network congestion and making it difficult for regular users to execute transactions unless they also pay exorbitant fees.

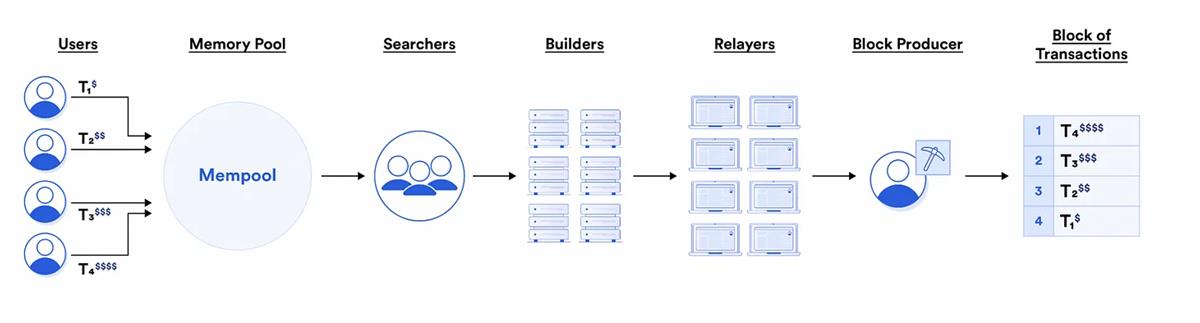

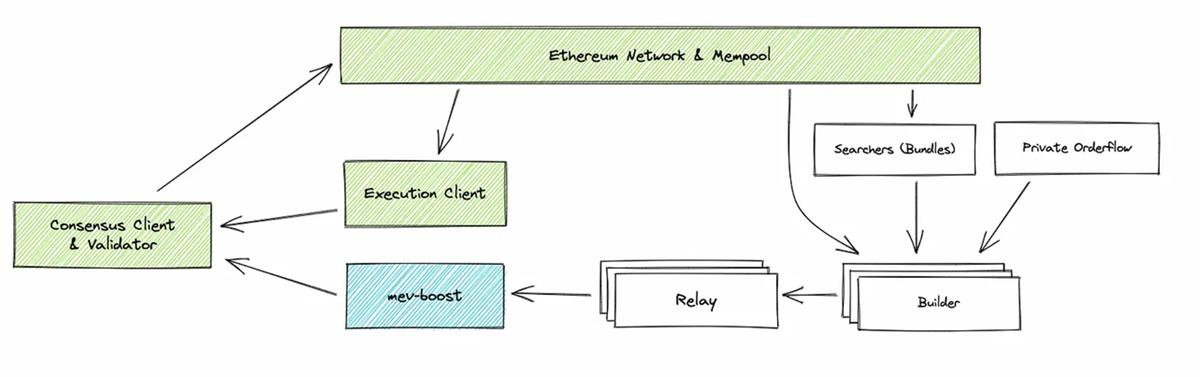

On the other hand, validators are among the primary beneficiaries in this scenario. Indeed, the greater the power, the greater the profit: because validators (at least theoretically) hold the authority to decide which transactions are processed, they can earn “ordering premium” fees by selecting transactions that yield them the most revenue. However, in practice, completing the entire MEV process—including searching, bundling, and execution—is too cumbersome for validators. As a result, most of this "ordering optimization" is outsourced to specialized intermediaries: searchers, builders, and relays. These entities act like "secretaries" to validators, streamlining the MEV process in exchange for a share of the profits. Specifically, searchers identify MEV opportunities, builders bundle these into complete "blocks," and relays transmit these full blocks to validators or actual block proposers. Thus, the overall structure of today’s MEV ecosystem looks like this:

As previously mentioned, while MEV-enabled arbitrage can bring some benefits—such as improved capital efficiency and ensuring price consistency across exchanges—it may impose significant negative externalities on end users, including higher transaction costs, slower execution speeds, and increased slippage (e.g., sandwich attacks). However, this is not the greatest risk MEV poses to blockchains—especially if validators collude, MEV could actually undermine the security guarantees of the blockchain consensus layer.

This security issue stems from misaligned incentives—in light of all these lucrative MEV opportunities, miners can earn more by optimizing transaction fees rather than adhering strictly to fixed block rewards. As Daian wrote:

Miners can therefore fork a high-fee block and retain some fees to attract others to build on that fork. In extreme cases, deviations from protocol incentives may lead to strategic confusion among economically rational miners, thereby reducing the security provided by block confirmations.

This is known as an "undercutting attack"—one of several ways MEV could compromise the fundamental security of blockchains. Other known attacks include "time-bandit attacks," where validators collude not to steal profitable transactions from the current block but instead rewrite past blocks to capture MEV opportunities. Moreover, MEV extraction does not even need to occur on-chain; it can be fully conducted off-chain via backdoor deals—for example, between large traders and validators.

Thus, we can see that MEV practices pose serious risks within the blockchain ecosystem.

Flashbots and the War Against MEV

Given the potentially severe consequences of unrestricted MEV, several projects and teams have emerged to mitigate these negative externalities. One of the most prominent teams in this space is Flashbots—a project dedicated to realigning MEV incentives in a way that sufficiently rewards validators for honestly building chains while minimizing the worst impacts on ordinary users.

To achieve this, Flashbots aims to take three distinct steps: (1) reveal the "dark forest" of MEV, (2) democratize MEV extraction, and (3) redistribute value back to the ecosystem. To accomplish the first goal, Flashbots developed a product called MEV-inspect, designed to "shine a light" into MEV's "dark forest," quantify its negative externalities, and highlight the scale of the problem.

Meanwhile, the goals of democratizing MEV extraction and redistributing value are more complex, involving a suite of evolving products that adapt as the scope and focus of the problem shift. In some ways, Flashbots’ product development history over the past two years itself mirrors the timeline of Ethereum’s growth and evolution.

Flashbots’ first major product release was MEV-Geth, a modified version of the Ethereum Golang client capable of better preventing MEV manipulation by routing transactions through private mempools. On top of this new client, Flashbots built an MEV auction market using a “first-price sealed-bid” mechanism (also known as “blind bidding”), where each participant submits only one bid, and bidders do not know what others have bid. Through this design, Flashbots mitigated the prior “bidding wars” discussed earlier.

The guiding principle behind creating MEV-Geth and the MEV market was to decentralize the power and responsibility of validators building blocks through a process of incentive realignment known as “proposer-builder separation.” Validators using the MEV auction no longer need to perform the complex tasks of MEV search and transaction bundling—they simply look at the MEV market, find which transactions offer the highest MEV returns, and place a single bid reflecting their actual preference. Furthermore, to prevent validators from including their own transactions and profiting from frontrunning user trades, the actual transaction details (buy orders, sell orders, liquidations, etc.) are not revealed until after the block is constructed.

So why would validators adopt this algorithm and give up the highly profitable MEV opportunities mentioned earlier? Because the Flashbots algorithm makes it easier and cheaper—by simply selecting MEV transactions from the market. As more high-quality MEV transactions flow through this market rather than directly on-chain, validators who stick with Flashbots earn higher returns. The results were impressive: shortly after MEV-Geth launched, over 90% of Ethereum validators began using this scheme, demonstrating the importance and effectiveness of incentive realignment in addressing underlying issues. However, as the Ethereum ecosystem evolved—transitioning from Proof-of-Work (PoW) to Proof-of-Stake (PoS) starting in September 2022—a shift in this “proposer-builder separation” model became necessary.

One reason PoS is more efficient than PoW is that under PoW, every node must independently build and propose blocks from scratch, whereas under PoS, only a few designated validators act as primary block proposers adding data to the blockchain. While this improves environmental and computational efficiency, the lure of MEV profits introduces additional centralization risks—especially if validators (“proposers”) collude with key market-side “builders.” Even Flashbots’ own private transaction pool could be vulnerable to collusion, and of course, placing trust in a single entity (like Flashbots) contradicts the ethos of decentralization.

The launch of MEV-boost decentralized the “supply side” of this MEV market. Unlike the previous setup where Flashbots’ private pool effectively held a monopoly, MEV-boost allows any builder running the software to submit blocks to all participating validators. For validators, having more builders competing to construct blocks increases their revenue and balances access to transactions, fostering a stronger and more secure ecosystem. Like MEV-Geth, this novel design realigned incentives across multiple parties to avoid centralization risks—and succeeded dramatically: over 85% of the network adopted this design, with Flashbots relaying only 34% of transactions.

Flashbots SUAVE

Even so, the task of eliminating all centralization risks and shielding decentralized finance from the most harmful effects of MEV remains unfinished. While Flashbots’ implementation of proposer-builder separation has already decentralized or redirected key validator powers and responsibilities to “builders,” introducing builders as separate entities from proposers, there remain important economies of scale in the builder role that could lead to its own centralization risks.

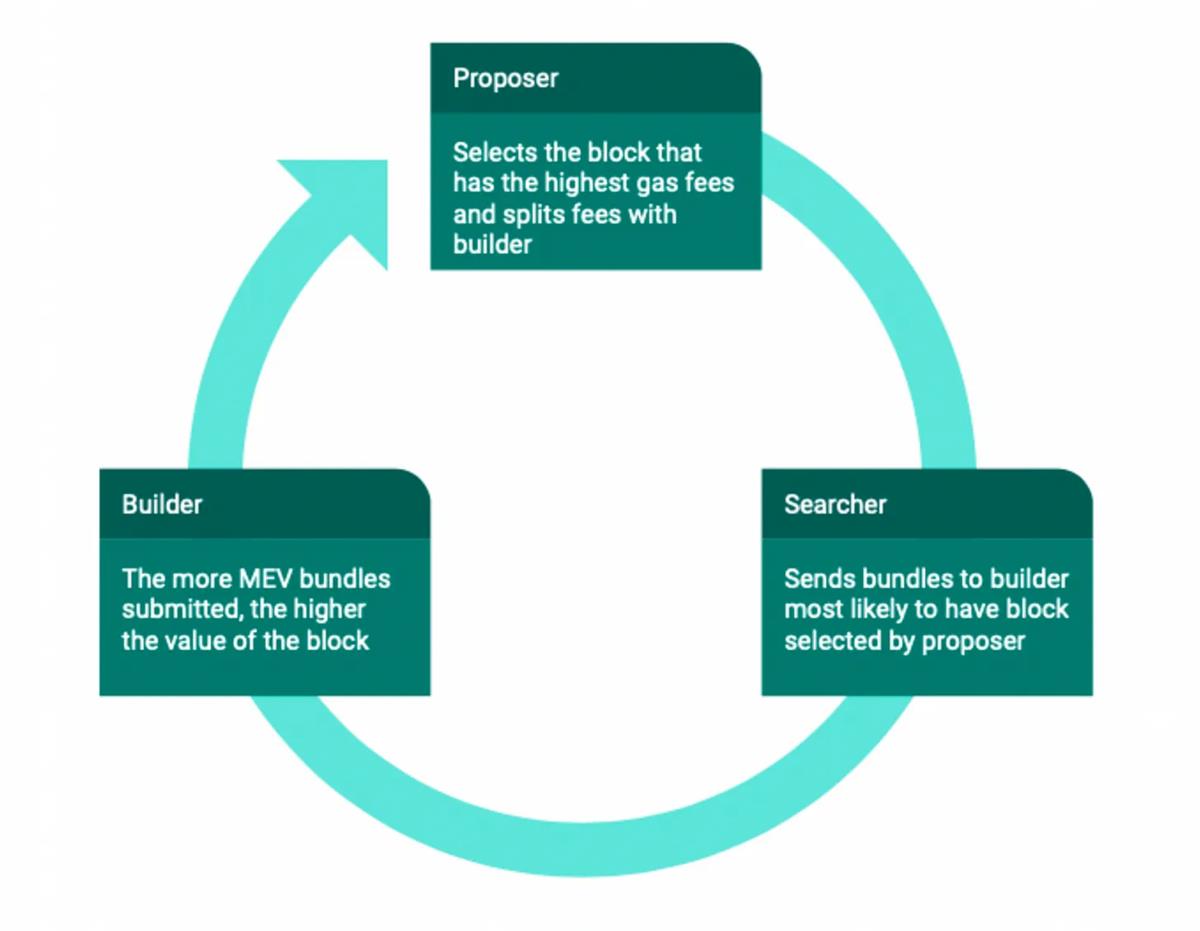

What do economies of scale in the builder role look like? Recall that searchers, builders, and relays play distinct roles: searchers identify MEV opportunities and send them to builders, who then package full blocks and pass them to relays. This means searchers must choose whom to send their findings to. To maximize returns, they will favor the highest-quality builders—those whose blocks are most frequently selected by validators. As more high-quality transactions flow to top-tier builders, a centralizing effect emerges: leading builders consistently receive the best MEV trades from searchers, reinforcing their dominance.

This builder centralization effect has proven real. In the past 24 hours at the time of writing, the top five builders produced approximately 90% of all MEV-boosted blocks. As this concentration grows, these oligopolists may begin leveraging their dominance to manipulate transactions—including collusion and censorship—potentially endangering the underlying blockchain’s security once again. This is precisely the motivation behind Flashbots’ latest initiative: Single Unified Auction for Value Expression (SUAVE)—a project aiming to decouple the block-building process from any individual blockchain and outsource it to a separate network, thereby decentralizing the builder role.

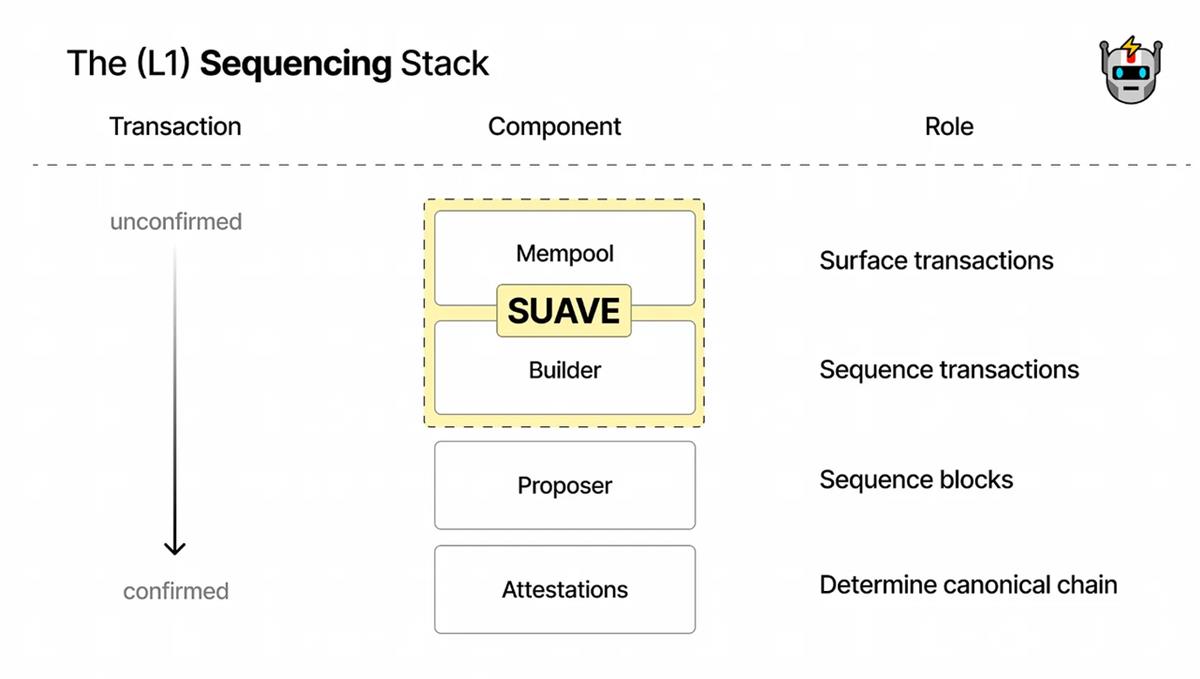

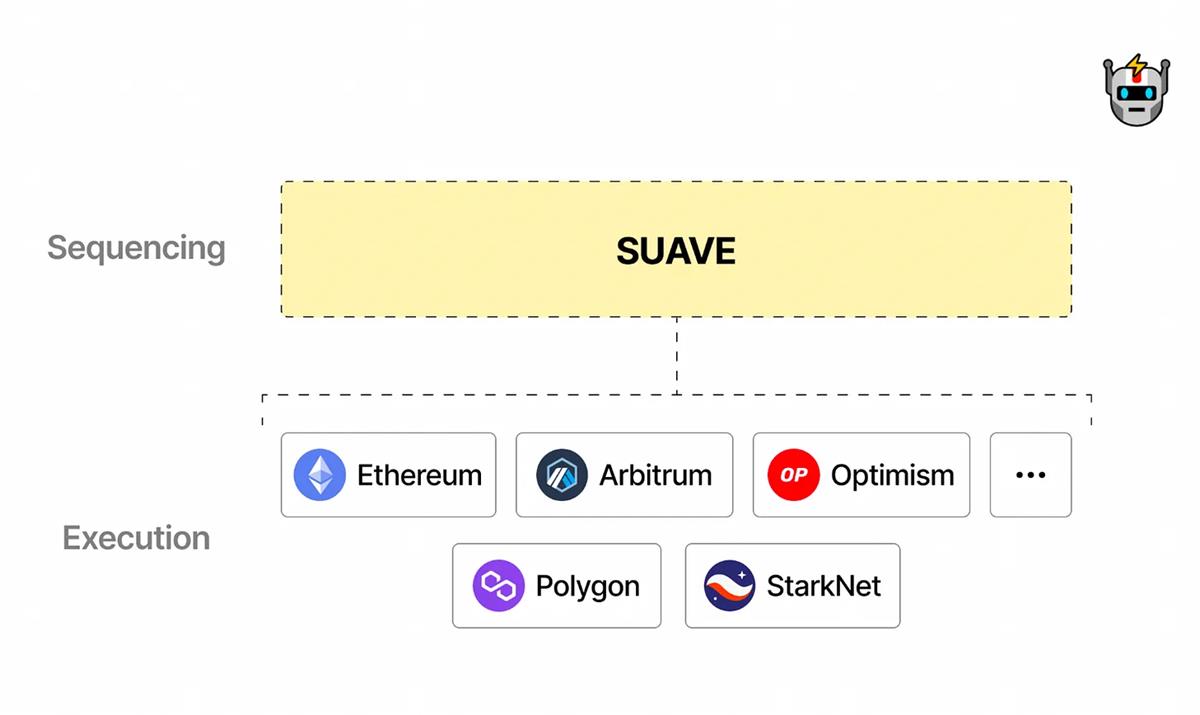

SUAVE is essentially an independent, dedicated block-ordering chain responsible for managing transaction mempools and the builder role, while native-chain validators (e.g., Ethereum) retain responsibility for proposing and attesting. As we can see, SUAVE represents a natural extension of the “proposer-builder separation” principle—placing proposers and builders on entirely separate chains so both can remain sufficiently decentralized and isolated. Moreover, SUAVE envisions serving as a universal ordering layer for many different chains. Whether you’re an Ethereum, Arbitrum, Polygon, or any other EVM-chain validator, you could use SUAVE to discover optimal MEV opportunities—not only within your native chain but also cross-domain MEV from cross-chain transactions, which cannot be captured by observing a single chain’s mempool alone.

Despite SUAVE’s ambitious vision—one that ultimately benefits all stakeholders and further decentralizes the Ethereum ecosystem—several critical design challenges remain unresolved six months after its November 2022 announcement. For example, a core question is whether SUAVE should be built as a standalone L1 chain (similar to Chainlink), implemented via rollup solutions, or leverage re-staking services from Ethereum validators such as Eigenlayer. Each approach involves unique trade-offs in terms of ease of implementation, validator retention, security, and flexibility, which we won’t delve into here.

Another key issue is whether SUAVE will launch its own token. Although the SUAVE forum currently denies any immediate plans to issue a token and states ETH will remain the native currency, questions remain about whether Flashbots will uphold this stance—particularly since launching a SUAVE token appears to be the most economically rational long-term move for Flashbots as a private company. Additionally, it’s reasonable to believe that Flashbots’ ability to raise a unicorn valuation of $1 billion during a bear market hinges implicitly on the expectation of a future SUAVE token launch.

So what’s stopping Flashbots from announcing a SUAVE token? It turns out that launching a token brings several thorny design decisions. Would the token serve a functional purpose, or would it merely be “another governance-only token”? If the token had utility, what form would that take? How could Flashbots incentivize its various stakeholders (different chains, end users, builders on Flashbots, etc.) to adopt and trust this new token over more established ones like ETH or even L2 tokens such as ARB? In any case, a complex incentive-alignment process would need to be solved—giving Flashbots ample reason to temporarily sidestep the issue.

Beyond Flashbots: The Big Picture of DeFi’s Future

While it’s still too early to determine what final form SUAVE will take—or whether this entirely new ordering chain will succeed in its original goal of truly mitigating MEV’s negative externalities through properly aligned incentives—I believe MEV and Flashbots exemplify the various trade-offs, challenges, and principles involved in designing genuinely decentralized financial systems.

First, as previously noted, MEV is a feature of blockchain technology, not a bug. These arbitrage opportunities and profit incentives for validators stem from the instant accessibility of blockchains and ensure capital efficiency in DeFi. The negative impacts of MEV—including network congestion, gas wars, and slippage for end users—are mere byproducts and negative externalities of this process.

By definition, negative externalities do not affect the agents engaging in the harmful behavior. In this case, network congestion and slippage imposed on end users do not harm the validators or arbitrage bots profiting from these activities. In traditional economics, purely market-driven systems struggle to address such externalities effectively. Historically, governments or regulators step in to correct market dynamics and minimize negative impacts (e.g., taxing tobacco and alcohol).

In contrast, DeFi is inherently trustless and opposes any form of human governmental enforcement. Its closest equivalent to an “enforcement body” lies in encoding rules and regulations directly into code (e.g., via smart contracts) to ensure determinism and transparency. Therefore, as the story of Flashbots illustrates, reducing the negative externalities of phenomena like MEV always depends on a complex process of incentive redesign and realignment. After all, much like Wall Street quant traders, DeFi arbitrage bots are not known for high moral standards or goodwill.

Using incentive redesign to reduce MEV’s negative externalities is not unique to the Flashbots team. Beyond Flashbots, many other teams are attempting to realign incentives and develop protocols to mitigate MEV’s impact. For example, Chainlink’s Fair Sequencing Service (FSS) leverages its decentralized oracle network to outsource the “transaction ordering” process from validators—achieving goals similar to those pursued by the SUAVE network. Another example is the “Coincidence of Wants” (CoW) mechanism on CoW Protocol (formerly Gnosis Chain), which automatically matches complementary trades (e.g., I want 1500 USDC for 1 ETH, and you want 1 ETH for 1500 USDC) and uses solver algorithms to ensure everyone trades at optimal prices.

However, conducting incentive redesign in a trustless, decentralized environment is extremely challenging because, fundamentally, you are trying to counteract economies of scale. For instance, in Flashbots’ case of builder centralization, builders who have already “proven their worth” are more likely to be “trusted” by searchers, who then send them higher-quality transactions—reinforcing their market leadership. Identifying, addressing, and implementing decentralized alternatives through incentive realignment is essentially a game of “whack-a-mole”—you never know what new centralized vulnerabilities or hidden economies of scale might emerge in a newly introduced incentive system, often only becoming apparent in hindsight.

Moreover, in a complex system with many different stakeholders and agents—such as a blockchain—it is nearly impossible to eliminate externalities altogether, as actions by one stakeholder will inevitably spill over and affect others. As Daian demonstrated in “Flash Boys v2.0,” many of these externalities can pose real threats that undermine the stability of the entire system. Therefore, any decentralized system—even those with well-designed game theory—will always carry inherent complexity, nuance, and fragility, where a single unexpected vulnerability could threaten its very existence.

Compared to centralized systems, decentralized systems lack obvious “single points of failure”—but ironically, this is precisely what sometimes makes them more dangerous than their centralized counterparts. If there is a flaw in the system design, every node could potentially become a “single point of failure.”

Finally, the story of MEV and Flashbots reminds us that maintaining the health of decentralized systems requires continuous, arduous effort—constant engagement in the “whack-a-mole” game. Trust in decentralized systems demands distributed responsibility and vigilance, especially given the immense economic incentives at stake: for better or worse, MEV is here to stay.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News