Decoding Bitcoin MEV: Another World Beyond Ethereum's Dark Forest

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

Decoding Bitcoin MEV: Another World Beyond Ethereum's Dark Forest

This report will analyze the increasing complexity of MEV on Bitcoin and assess its impact on the broader ecosystem.

Author: Jeffrey Hu

Translation: TechFlow

This article is co-authored by Jeffrey HU from HashKey Capital, Jinming NEO, and George ZHANG from Flashbots.

Introduction

The concept of Bitcoin MEV (Miner Extractable Value) first emerged as early as 2013. Although still relatively nascent compared to Ethereum's MEV, the thriving Bitcoin ecosystem—fueled by meta-protocols such as BRC-20, Ordinals, and Runes—promises greater programmability, expressiveness, and MEV opportunities in the future.

This report analyzes the increasing complexity of MEV on Bitcoin and assesses its impact on the broader ecosystem.

Why Is Bitcoin MEV Gaining More Attention?

Prior to the introduction of Ordinals, MEV on Bitcoin was neither widely recognized nor significant. Focus remained largely on Lightning Network and sidechain mining attacks. However, the Taproot upgrade enhanced Bitcoin’s expressiveness and programmability, enabling the emergence of meta-protocols like Ordinals and Runes, which brought MEV into prominence. Bitcoin’s 10-minute block time further exacerbates this issue, making inexperienced users more vulnerable to various MEV attacks—such as fee sniping during inscription auctions. As block rewards decline, miners’ profitability is impacted, incentivizing them to maximize transaction fees, potentially explaining the rise in MEV activity.

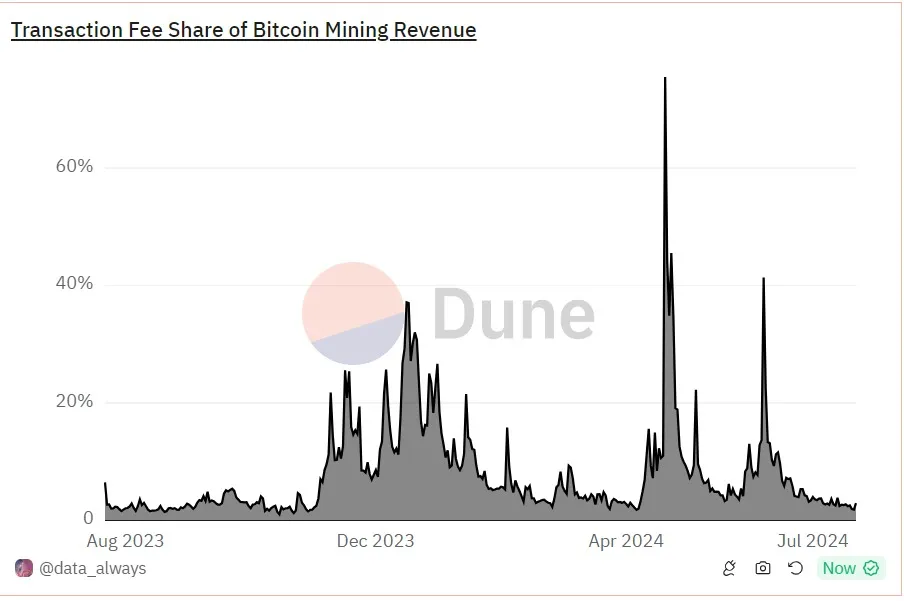

The chart below illustrates how transaction fees surged relative to block rewards around the highly anticipated launches of Ordinals and Runes, at one point accounting for over 60% of total Bitcoin mining revenue.

Source: Dune analytics (@data_always), ratio of transaction fees to mining rewards, as of July 22, 2024.

To date, we have seen growing BTCFi application development, transforming Bitcoin from being perceived solely as digital gold or a payment network into a rapidly expanding ecosystem with broadening utility. This evolution may unlock additional MEV opportunities on Bitcoin.

How Bitcoin MEV Differs from Ethereum MEV

Discussions around Bitcoin MEV remain limited, largely due to fundamental architectural differences between Bitcoin and Ethereum.

Architectural Design

Ethereum operates via the Ethereum Virtual Machine (EVM), executing smart contracts and maintaining a global state machine to enable programmability.

Ethereum uses an account-based model, processing transactions sequentially using nonces. This means transaction order affects outcomes, allowing searchers to easily identify MEV opportunities and insert their own transactions before or after user transactions. For example, if both Alice and Bob submit transactions to Uniswap to swap 1 ETH for USDT, the one executed first in the block will receive more USDT.

In contrast, Bitcoin’s scripting language lacks statefulness like Ethereum’s and instead uses the UTXO model. In standard Bitcoin transfers, only the designated recipient can spend bitcoins with a valid signature, eliminating competition among users for those funds. However, Bitcoin also allows UTXOs that can be unlocked by multiple parties through scripts or SIGHASH flags. The first confirmed transaction gets to spend the UTXO. Nevertheless, since each UTXO’s unlocking conditions depend only on itself and not other UTXOs, competition is confined to that specific UTXO.

Altcoins on Bitcoin

Beyond these foundational design differences, the introduction of non-BTC valuable assets introduces incentives for Miner Extractable Value (MEV). The MEV generated in these scenarios stems from protocol designers attempting to define asset ownership and validity of on-chain actions using scripts and UTXOs—Bitcoin’s native data structures. Since events are defined by sequence, there is inherent incentive to compete for ordering, thus creating MEV.

If only standard BTC transfers were considered, rational miners would simply include valid transactions based on fees, charging according to transaction size. However, when Bitcoin transactions go beyond simple transfers—such as minting new valuable assets like Runes—miners may adopt alternative strategies beyond fee maximization: 1) censoring transactions and replacing them with their own mints; 2) demanding higher fees (on-chain, off-chain, or via sidechains); 3) pitting users against each other in bidding wars, triggering fee spikes.

Minting

A direct example is the minting process for assets like Runes or BRC20, which often impose hard caps. The first confirmed mint transaction succeeds, while others become invalid. Hence, transaction ordering becomes critical, opening up MEV opportunities through sequencing.

Moreover, the concept of rare satoshis introduced by Ordinals has even raised concerns about miners potentially causing block reorganizations during halvings to capture high-value rare sats.

Staking

Beyond minting, staking protocols like Babylon also set upper limits per staking epoch. Even if users exceed the cap, they can still construct and send BTC into the staking lock script, but such deposits won’t count as successful stakes and won’t qualify for future rewards. In other words, the order of staking transactions is equally crucial.

For instance, shortly after Babylon’s mainnet launch, the initial staking cap was set at 1,000 BTC, resulting in approximately 300 BTC overflowing and requiring unbonding.

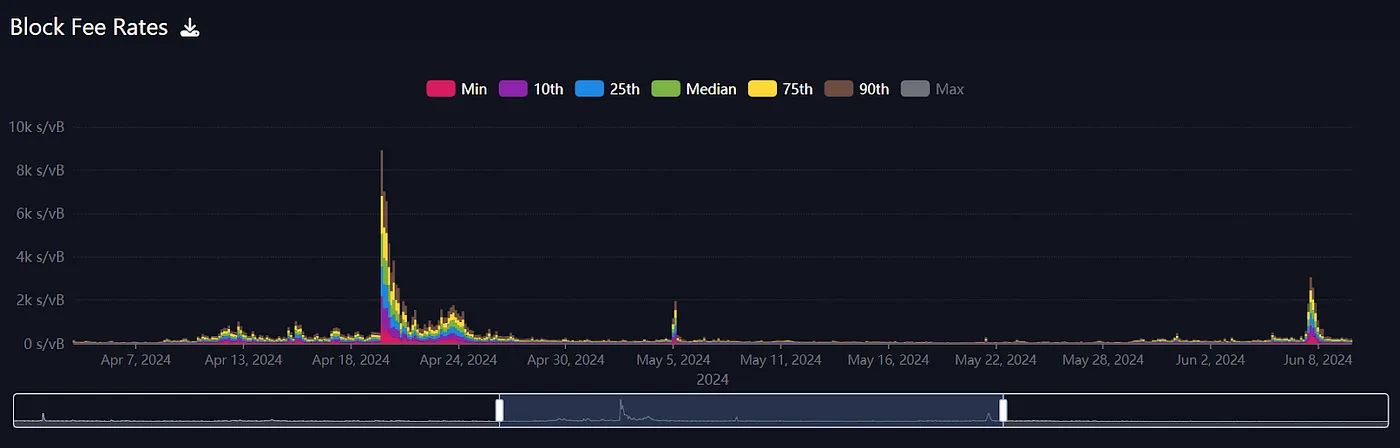

Fee rate spiked to 1,000 sats/vBytes at Babylon mainnet launch. Source: Mempool.space

Beyond on-chain minting/inscribing and staking, certain activities on sidechains or rollups are also susceptible to MEV. We provide further examples in the “MEV Events on Bitcoin” section.

What Constitutes Bitcoin MEV?

So, what counts as MEV on Bitcoin? After all, the definition of MEV varies across contexts.

Generally speaking, Bitcoin MEV refers to how miners extract maximum profit by manipulating the block production process. We can broadly categorize it as follows:

-

Users paying extra fees: Users seeking faster confirmations often use off-chain transaction acceleration services, typically at a premium cost, paying higher fees to prioritize their transactions. Traders can also pay miners higher fees via mechanisms like RBF (Replace-by-Fee) and CPFP (Child-Pays-for-Parent) to expedite confirmation. Low-fee transactions usually face longer confirmation times, as profit-driven miners prioritize more lucrative ones.

-

User-miner collusion: Users collude with miners to censor or include certain strategically important transactions. For example, malicious actors might collude with miners to exclude penalty transactions on the Lightning Network, thereby illicitly claiming channel funds. Other emerging systems like BitVM and their associated penalty transactions face similar risks.

-

Bitcoin miners mining on sidechains/L2s: This includes various early merged mining schemes where miners leverage Bitcoin’s hash power to secure another network. Merged mining could lead to miner centralization, as large miners may use their dominant hash power on the mainchain to influence block production and ordering on L2s, capturing disproportionate L2 mining rewards and potentially compromising L2 network security.

Market-based fee bidding methods like RBF play a relatively positive role in the overall economic system by promoting free-market dynamics. However, when users make out-of-band payments to mining pools, this undoubtedly threatens the network’s decentralization and censorship resistance, commonly referred to as “MEVil.”

Examples of Bitcoin MEV

Based on the above classifications, several MEV cases emerge.

Non-Standard Transactions

Bitcoin Core software only allows nodes to relay standard transactions, capped at 100 kvB. However, mining pools still include high-fee non-standard transactions in blocks, often excluding lower-fee ones.

Notable examples include:

-

Block 776,884: Mined by Terra Pool, contained an inscription transaction of 849.93 kvB—a 1-minute MP4 video of a frog holding a drink—earning the miner 0.5 BTC in fees.

-

Block 777,945: Included a 975.44 kvB WEBP image of 4000 x 5999 pixels, generating 0.75 BTC in fees for the miner.

-

Block 786,501: Earned approximately 0.5 BTC in fees for inscribing a JPEG image of Julian Assange on the cover of Bitcoin Magazine, sized 992.44 kvB.

By default, Bitcoin Core nodes only forward standard transactions. Thus, non-standard transactions must be sent directly to mining pools via private mempools. Private mempools allow pools to accept and prioritize such transactions. While this speeds up processing, increased reliance on private mempools could lead to greater pool centralization and censorship risks. Clearly, some pools are already capitalizing on the profitability of private mempools.

For instance, Marathon Digital launched “Slipstream,” a direct transaction submission service allowing clients to submit complex and non-standard transactions.

MEV Events on Sidechains / L2s

The Stacks sidechain uses a unique consensus mechanism—Proof of Transfer (PoX)—enabling Bitcoin miners to mine Stacks blocks and settle transactions on the Bitcoin blockchain while earning STX rewards.

In the past, Stacks used a simple miner election mechanism where Bitcoin miners with higher hash power had a greater chance of mining Stacks blocks, censoring commitments from other miners, and monopolizing all rewards. If more miners adopt this strategy, future Stackers could see reduced yields.

Impacts on the ecosystem:

-

Excluding honest miners’ commitments reduces final rewards passed on to Stackers.

-

If large miners continue abusing their computational advantage to exclude honest participants, centralization risk increases, allowing a few miners to monopolize all Stacks rewards.

However, this issue will be addressed by Stacks’ upcoming Nakamoto upgrade, which aims to render such strategies unprofitable. The upgrade shifts from simple miner elections to a lottery algorithm combined with Assumed Total Commitment with Carryforward (ATC-C) technology, reducing profitability of MEV mining. Miners must now consistently participate in at least 5 out of the last 10 blocks to qualify for the lottery. A miner’s probability of winning a Stacks block equals their BTC expenditure divided by the median total BTC commitment over the past 10 blocks. This diminishes the ability of miners to gain disproportionate benefits by censoring others' commitments.

Bidding Wars for Alternative Asset Transactions

MEV related to alternative assets such as Ordinals and Runes falls into two previously mentioned categories:

-

Pools extracting extra value: Mining pools can capture additional value by including Bitcoin Ordinals or rare satoshis in blocks and transactions.

-

Fee-sniping transactions: Traders may bid competitively to get transactions tied to these alternative assets included in blocks.

For mining pools, the initial success of Runes has created a new revenue stream. For example, heightened anticipation around the Runes launch coincided with the halving event, driving network transaction volume and fees to record highs, as many users rushed to include their transactions in the historic halving block. Post-halving, transaction fees surged beyond 1,500 sats/vByte (up from under 100 pre-halving). ViaBTC capitalized on this spike by mining the halving block concurrent with the Runes launch, earning 40.75 BTC in profit—37.6 BTC of which came from Runes-related transaction fees. With block rewards now halved, Runes-related fees have become a vital income source for miners.

Source: Mempool.space

Source: Mempool.space

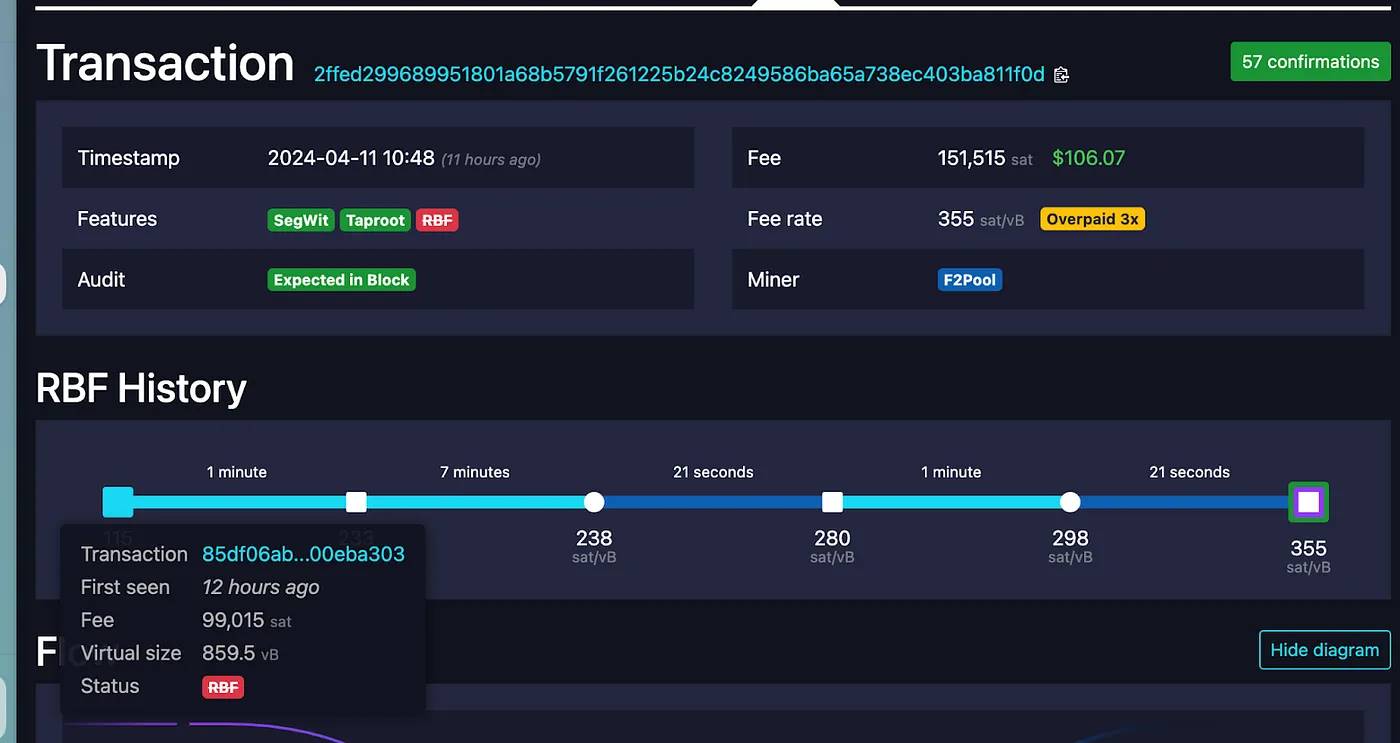

For traders, Bitcoin transactions involving Runes and Ordinals use SIGHASH_SINGLE|SIGHASH_ANYONECANPAY within Partially Signed Bitcoin Transactions (PSBTs), allowing one input signature to correspond to one output. Combined with mempool transparency, this enables many buyers to detect potentially profitable trades. Consequently, traders frequently employ RBF and CPFP, leading to competitive fee wars from which miners extract MEV. For example, when a seller lists an asset, buyers can bid competitively and use RBF to increase their transaction fees upon detecting rivals, hoping their transaction gets confirmed first.

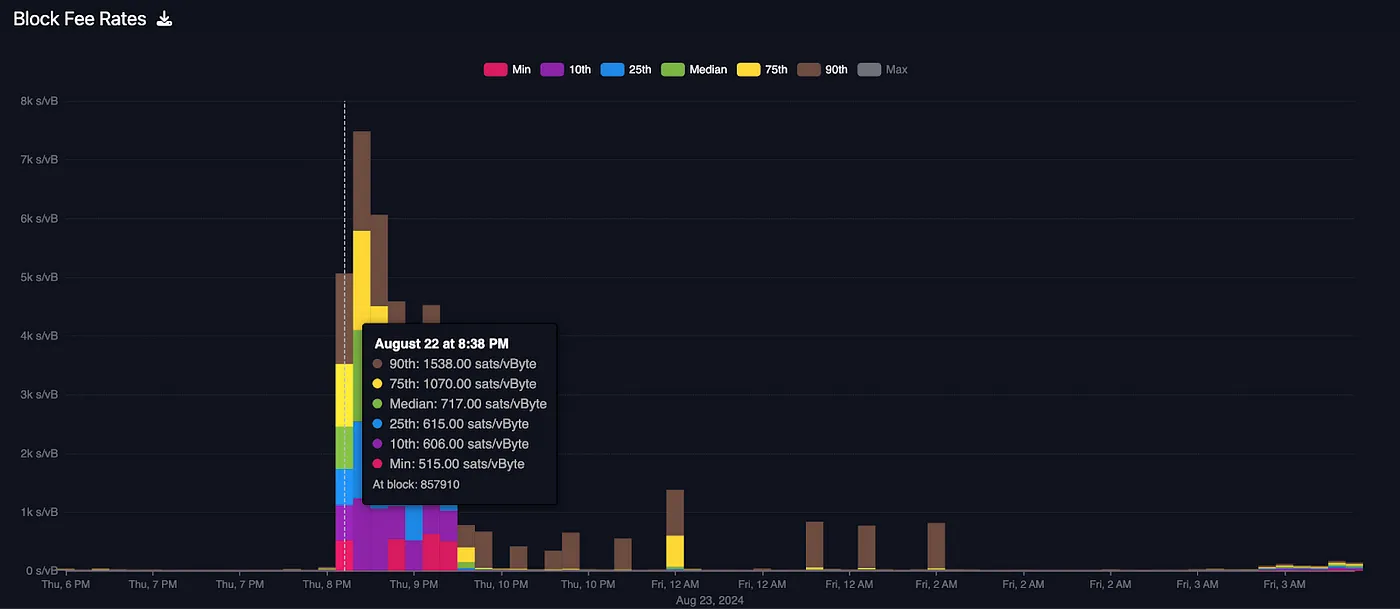

A classic case of trader competition is transaction ID 2ffed299689951801a68b5791f261225b24c8249586ba65a738ec403ba811f0d. After the seller listed the asset, this transaction was replaced multiple times via RBF with fee rates of 238, 280, 298, and finally 355 sat/vB.

Source: Mempool.space

Another example involves the OrdiBots minting process on Magic Eden. Multiple users fell victim to frontrunning attacks. The OrdiBots inscription on Magic Eden used PSBTs. The existence of PSBTs combined with Bitcoin’s 10-minute block interval allows potential buyers to compete for the same transaction by introducing different addresses and signatures, simply by paying higher fees. This caused some whitelisted users to fail in minting due to interference from frontrunning bots. (The team later apologized and promised affected users custom OrdiBots as compensation.)

However, not all MEV-related techniques or events harm users. In some cases, MEV tools can actually protect user assets. For example, without RBF, erroneous transactions couldn't be recovered, leaving unconfirmed transactions stuck indefinitely, incurring opportunity costs. Moreover, RBF usage contributes to Bitcoin network security. As block subsidies decrease relative to transaction fees in the future, transaction fees will play a crucial role in incentivizing miners to maintain network participation. Bitcoin developer Peter Todd actively advocates for the benefits of RBF and recommends miners implement full RBF.

Key Technical Components Enabling Bitcoin MEV

What key technical components or methods on Bitcoin enable these MEV opportunities? Commonly involved areas include mempools, RBF (Replace-by-Fee), CPFP (Child-Pays-for-Parent), mining pool acceleration services, and mining pool protocols.

Mempools

Like Ethereum and other typical blockchain networks, Bitcoin features a transaction pool structure storing transactions received by P2P nodes but not yet included in blocks. The transparent and decentralized nature of the mempool fosters an environment conducive to MEV, enabling all transactions to propagate to miners.

However, unlike Ethereum’s gas mechanism, Bitcoin fees depend solely on transaction size. Therefore, Bitcoin’s mempool functions more like a direct block space auction market, where it’s visible who is bidding for inclusion in the next block and at what price.

Since different nodes receive varying transactions via P2P propagation, each node maintains a distinct mempool. Additionally, each node can customize its forwarding policy (mempool policy), defining which transactions it accepts and relays. Mining pools can similarly choose which transactions to include in blocks based on preferences (though economically, they tend to prioritize high-fee transactions). For example, Bitcoin Knots nodes filter out all Ordinals transactions, while Marathon Mining created a pixel-art logo visible on its block explorer.

Block 836361 (pixel colors indicate fee rate). Source: mempool.space

Hence, users might consider sending transactions directly to specific miners or pools to accelerate inclusion. However, this approach risks undermining two core values cherished by the Bitcoin community: privacy and censorship resistance.

Transactions propagated through P2P nodes—rather than sent directly (e.g., via RPC endpoints) to miners or pools—help obscure the origin, making it harder for miners or pools to censor transactions based on identifiable information.

Beyond transaction acceleration services, users can alternatively use RBF and CPFP to speed up their transactions.

RBF and CPFP

Replace-by-Fee (RBF) and Child-Pays-for-Parent (CPFP) are common methods users employ to boost transaction priority.

RBF (Replace-by-Fee) allows an unconfirmed transaction in the mempool to be replaced by a conflicting transaction (referencing at least one identical input) that pays a higher fee rate and total fee. Similar to earlier discussed mempool policies, RBF can be implemented in various ways. The most common form is opt-in RBF, designed under BIP125, where only specially marked transactions can be replaced. Another variant is full RBF, where any transaction can be replaced regardless of marking.

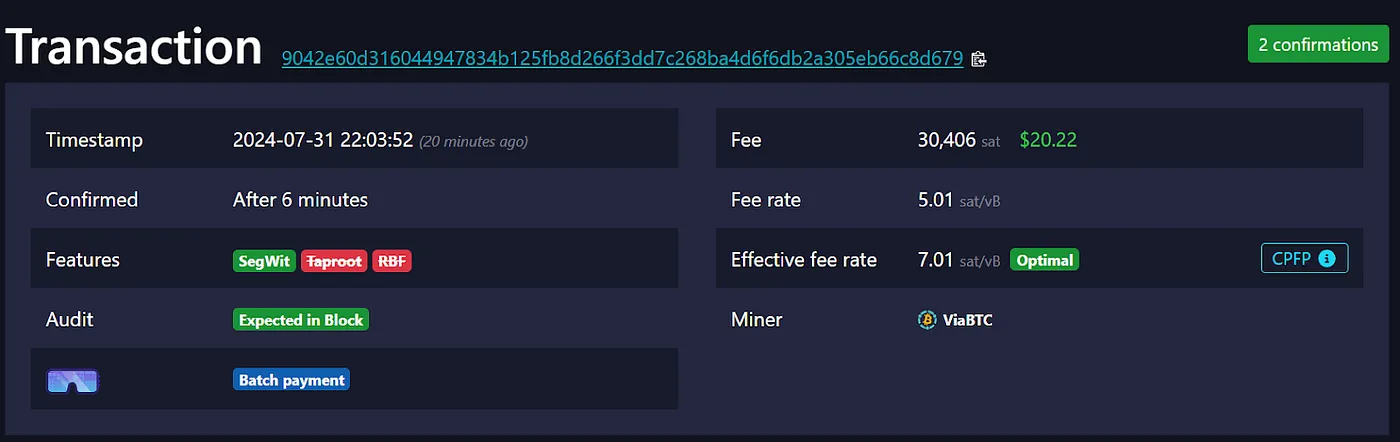

CPFP (Child-Pays-for-Parent) takes a different approach to accelerate confirmation. Instead of replacing a stuck transaction as in RBF, the recipient can accelerate a pending parent transaction by spending its UTXO in a child transaction with a higher fee rate. This incentivizes miners to bundle both transactions into the next block. Thus, you might occasionally see very low-fee transactions included in a block despite high prevailing fees—these likely benefited from CPFP (as the subsequent transaction paid the fee).

Transaction using CPFP to confirm a low-fee parent transaction (7.01 sat/VB). Source: mempool.space

The key difference between RBF and CPFP is that RBF allows the sender to replace a pending transaction with a higher-fee version, whereas CPFP enables the receiver to accelerate confirmation by attaching a higher-fee child transaction. CPFP is particularly useful for transactions exiting the Lightning Network (e.g., anchor outputs). In terms of cost, RBF is relatively more efficient as it doesn’t require additional block space.

Out-of-Band Fee Payments and Pool Acceleration Services

Beyond RBF (Replace-by-Fee) and CPFP (Child-Pays-for-Parent), users can also use out-of-band fee payments to accelerate their transactions. Many mining pools offer free and paid transaction acceleration services, allowing users to submit their txID for faster inclusion. Paid services require users to pay fees supporting the pool. Because such payments occur outside the Bitcoin network (e.g., via websites, credit cards), they are termed out-of-band fee payments.

While out-of-band payments offer remedies for transactions unable to use RBF or CPFP, widespread long-term adoption could undermine Bitcoin’s censorship resistance.

Mining Pool Protocols

Earlier discussions treated mining pools and miners as a single entity, but in reality, they require division of labor and coordination. Mining pools aggregate miners’ hash power, perform mining, and distribute rewards based on contribution. This cooperation requires specific protocols.

In common pool protocols like Stratum v1, the pool sends miners a block template (including header and coinbase info), and miners perform hashing accordingly. Tools like stratum.work can visualize Stratum messages from various pools.

Under this setup, miners cannot choose which transactions to include; the pool selects and constructs the template, assigning tasks to miners.

Thus, under Stratum v1, roles roughly map to the Ethereum ecosystem as follows:

-

Miners: Fulfill partial proposer duties (performing hashing).

-

Mining Pools: Act as both builders (using hash results from miners) and block proposers.

What Lies Ahead?

Promising solutions are being developed to mitigate the negative impacts of MEV on Bitcoin.

New Protocols

Newer mining pool protocols like Stratum v2 and BraidPool allow miners to autonomously select transactions to include. Stratum v2 has already been adopted by some pools (e.g., DEMAND) and mining firmware (e.g., Braiins), enabling individual miners to build their own block templates. This improves data transmission security, decentralization, and efficiency while reducing risks of transaction censorship and MEV on Bitcoin.

Accordingly, this trend suggests that the roles of pools and miners may evolve differently from Ethereum’s PBS (Proposer-Builder Separation) model.

Additionally, new transaction relay strategies under discussion in Bitcoin Core—such as the much-debated v3 transaction policy and enhanced cluster mempool—could bring change. However, their implications—for example, on implementing Lightning Network channel exits—are still under review and discussion.

Impact of Declining Mining Rewards

Reduced mining rewards pose a significant challenge. As block rewards continue to shrink in the future, this could impact the network in multiple ways.

Some issues were identified early by Bitcoin developers, such as fee sniping, where pools might deliberately re-mine prior blocks to capture fees. Bitcoin Core has implemented measures to counter fee sniping, though current approaches still need refinement.

Beyond native transaction fees, alternative assets may become sustainable revenue sources in the future. Accordingly, some projects are building infrastructure to more effectively identify valuable transactions involving alternative assets. For example, Rebar is developing an alternative public mempool to better detect transactions linked to valuable alt-assets.

Yet, as discussed in the “Out-of-Band Fee Payments” section, the impact of these off-chain economic incentives on Bitcoin’s self-regulating, incentive-compatible system remains to be seen.

In any case, MEV on Bitcoin shares similarities with Ethereum but differs due to architectural and philosophical distinctions. Increasing Bitcoin utility, declining block subsidies, and the evolving BTCFi ecosystem will bring MEV-related factors into sharper focus.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News