Solana Co-Founder's New Article: Solana's Concurrency Leadership Mechanism, Solving MEV and Building a Global Price Discovery Engine

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

Solana Co-Founder's New Article: Solana's Concurrency Leadership Mechanism, Solving MEV and Building a Global Price Discovery Engine

Solana's broader vision is to build a global, permissionless price discovery engine capable of competing with the best performance of any centralized exchange (CEX).

Author: Anatoly Yakovenko

Translation: TechFlow

Overview

MEV is a fundamental issue in permissionless blockchains. Like most permissionless blockchains, Solana aims to minimize MEV extracted by chain operators from users.

Solana’s approach is to reduce MEV by maximizing competition among leaders (i.e., block producers). This means shortening slot times, reducing the number of consecutive slots assigned to a single leader, and increasing the number of concurrent leaders per slot.

In general, more leaders per second mean users have more options after waiting T seconds to pick the best quote from upcoming leaders. More leaders also mean better leaders can offer blockspace at lower cost, making it easier for users to transact only with good leaders and exclude bad ones. The market should decide what is good and what is bad.

Solana’s broader vision is to build a global, permissionless price discovery engine capable of competing with the best performance of any centralized exchange (CEX).

If a market-moving event occurs in Singapore, the message still needs to travel via fiber at light speed to a CEX in New York. Before that message reaches New York, leaders in the Solana network should already have broadcast it in a block. Unless there is a simultaneous physical internet partition, by the time the message arrives in New York, Solana’s state will already reflect it. Therefore, there should be no arbitrage opportunity between the New York CEX and Solana.

To fully achieve this goal, Solana needs many concurrent leaders and highly optimistic confirmation guarantees.

Configuring Multiple Leaders

Similar to the current leader schedule, the system will configure each slot with 2 leaders instead of 1. To distinguish the two leaders, one channel is labeled A and one B. A and B can rotate independently. Implementing this plan requires answering the following questions:

-

What happens if block A and B arrive at different times or fail?

-

How do we merge transaction ordering from blocks A and B?

-

How is block capacity allocated between A and B?

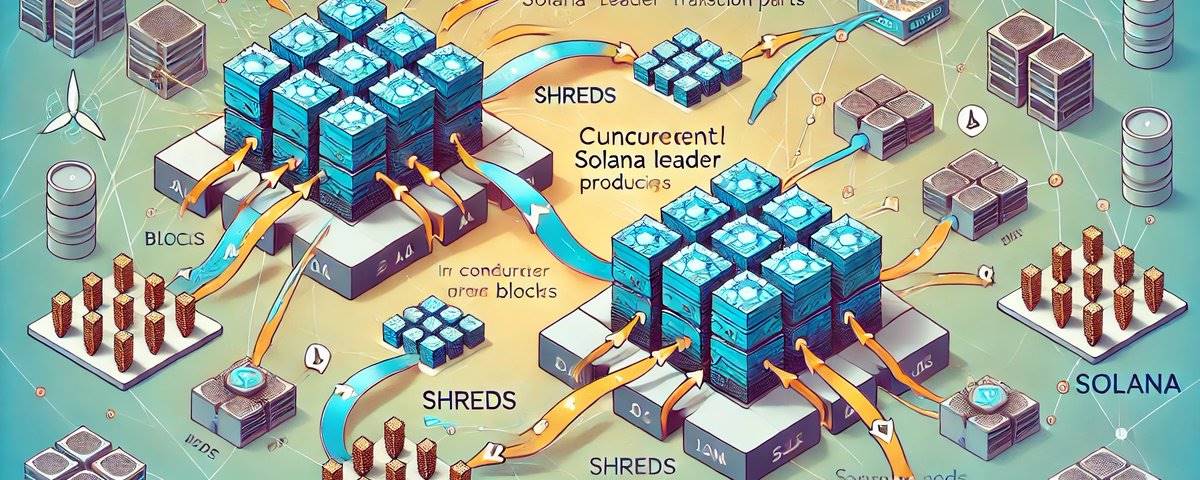

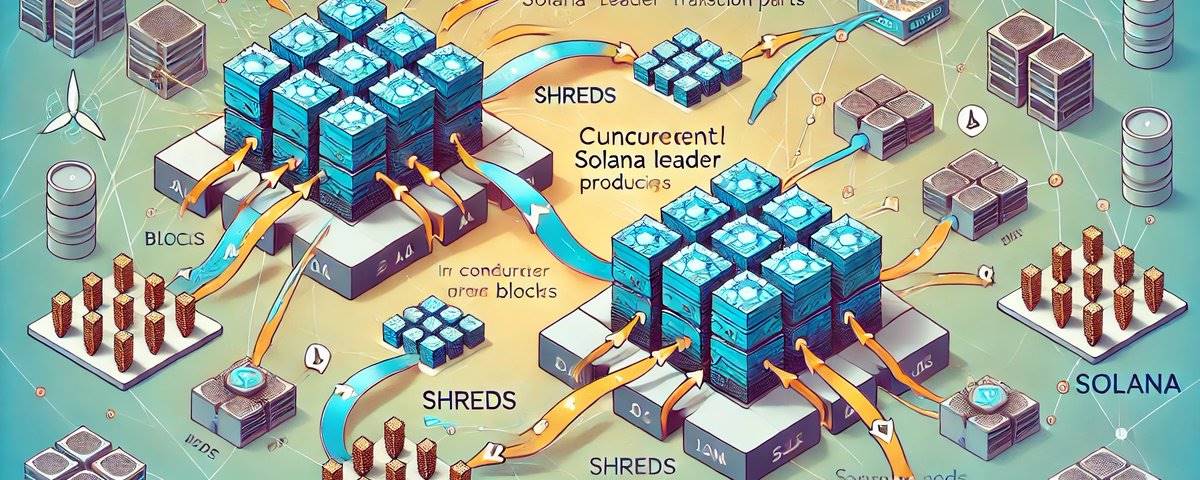

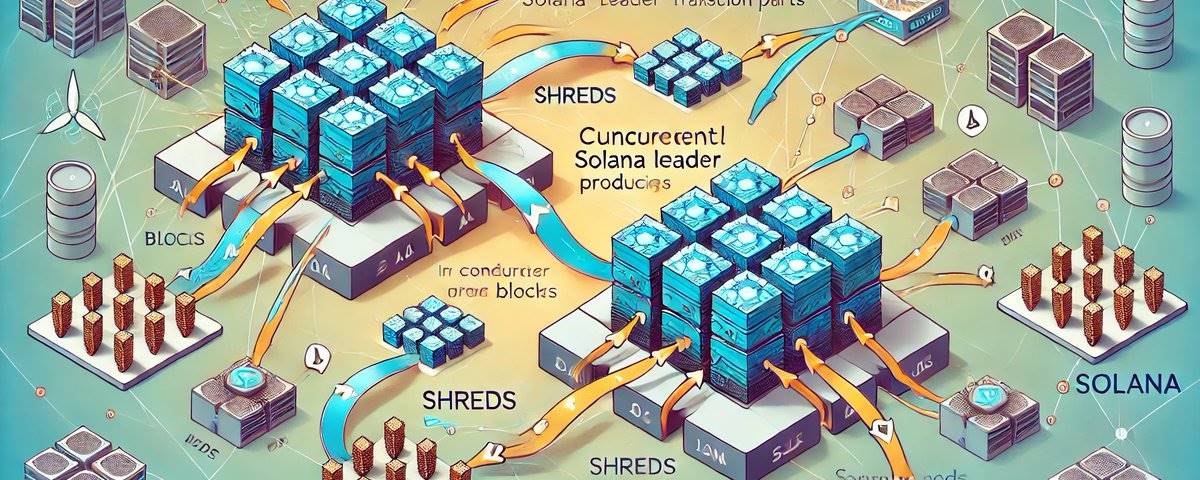

Transmitting Concurrent Blocks

To understand the process, we need a quick overview of Turbine.

When a leader builds a block, it splits it into shards. A batch of 32 shards becomes a 32-of-64 erasure-coded set. A batch of 64 shards is merklized and signed at the root, and these are linked to the previous batch.

Each shard is sent along an independent, deterministic random path. Retransmitters for each final batch sign the root.

From the receiver's perspective, each node needs to receive 32 shards from verified retransmitters. Any missing shards are randomly repaired.

This number can be increased or decreased with minimal impact on latency.

Assuming shard path sampling among retransmitters is sufficiently random and stake-weighted, the stake required to co-partition the network would far exceed ε stake, both in terms of arrival time and data. If a receiver detects that 32/64 (configurable) shards per batch arrive within time T, it is likely true for every node. This is because 32 random nodes are large enough that it’s unlikely they’d all randomly fall into the same partition.

If a partition does occur, consensus must resolve it. This doesn’t affect security but is relatively slow.

Multi-Block Production

For single-block transmission, each receiver (including the next leader) observes shard batches arriving for each block. If a block is incomplete within T milliseconds, the current leader skips it and builds a fork without it. If the leader is wrong, all other nodes vote for the block, causing the leader’s block to be skipped. Non-faulty leaders immediately switch to the heaviest fork indicated by votes.

In multi-block transmission, each node must wait up to T milliseconds before voting on the observed block partition. With two concurrent leaders, possible outcomes are: A, B, or both A and B. Additional delay is only incurred when blocks are delayed. Under normal operation, all blocks should arrive simultaneously, allowing validators to vote immediately once both arrive. Thus, T may practically be close to zero.

A key attack to defend against is whether a leader with minimal stake can slightly delay transmission of a block near the slot boundary, reliably causing network splits and forcing the network to spend significant time resolving via consensus. Part of the network would vote for A, part for B, and part for both. All three split scenarios require consensus resolution.

Specifically, the goal for zero neighborhood should be ensuring nodes recover blocks simultaneously. If an attacker has a coordinated node in the zero neighborhood, they could transmit 31/64 shards normally and selectively delay the last shard to attempt creating a partition. Honest nodes can detect which retransmitters are delaying and immediately push missing shards to them once any single honest node recovers the block. Retransmitters can continue as soon as they receive or recover the shard from anywhere. Therefore, the block should be recovered by all nodes shortly after any one honest node recovers it. Testing is needed to determine the optimal wait time—whether absolute, weighted by shard arrival time, or using stake-based node reputation.

The probability of coordinated leaders and retransmitters per block is approximately P_leader_stake × (64 × P_retransmitter_stake). With 1% stake, an attacker could attempt such attacks in half the shard batches scheduled under their leadership. Thus, detection and mitigation must be robust.

This attack has minimal impact on the next leader because asynchronous execution allows unused capacity to roll over. If the current leader forces the next leader to skip a slot and that leader has four consecutive slots, the unused capacity from the skipped slot can carry over, allowing transactions from the skipped slot to be re-included.

Merging Concurrent Blocks

If users send the same transaction to both leader A and B to increase inclusion chances or rank first in the block, it causes resource waste. In such cases, increasing the number of concurrent leaders yields limited performance gains, as they merely process double the spam transactions.

To avoid duplicate transactions, the top N bits of the fee payer will determine which leader channel the transaction is valid in. In this example, the highest bit selects A or B. The fee payer must be assigned to an exclusive channel so leaders can verify its validity and ensure lamports (the smallest currency unit on Solana) aren’t exhausted across other leaders.

This forces spammers to pay fees at least twice for logically identical transactions. However, to increase the chance of being first, spammers might still send duplicates.

To deter this, users can optionally include an additional 100% burn order fee on top of the leader’s priority fee. Transactions with the highest order fee execute first. Otherwise, FIFO (first-in, first-out) ordering applies. In ties, a deterministic random permutation resolves order. For spammers, paying a higher order fee to execute first becomes more cost-effective than paying twice for inclusion.

To handle bundles and reordered transaction sequences, the system must support bundled transactions with an order fee covering the entire sequence’s sorting cost. Fee payers are only valid in their designated channel, so bundles can only manipulate sequencing within their own channel.

Alternatively, order fees may not be necessary. If FIFO ordering is used and spammers are consistently charged priority fees across all channels, perhaps simply allowing the market to determine the cost of paying N leaders for higher inclusion probability versus paying the most recent likely leader for fastest inclusion is sufficient.

Managing Block Resources

In a blockchain network with two concurrent leaders, each system-wide block capacity limit must be evenly shared. Specifically, not just total capacity, but each individual limit—for instance, write-lock limits—must be halved. No account can exceed 6 million compute units (CUs), and each leader can schedule at most 24 million CUs. This ensures that even in worst-case scenarios, the merged block won’t exceed total system capacity.

This mechanism may cause fee volatility and underutilization of resources, since scheduling priority fees will be determined by each leader’s capacity, while each leader has limited visibility into the scheduling status of other concurrent leaders.

To mitigate underutilization and resulting fee spikes, any unused block capacity should roll over to future blocks. That is, if the current merged block uses X less than capacity in terms of write locks, total bytes, or total compute units (CUs), then K×X should be added to the next block, where 0 < K < 1, up to some maximum. Asynchronous execution can lag behind the chain tip by up to one epoch, so capacity rollover can be quite aggressive.

Based on recent block data, most blocks are typically filled to about 80%, while write-lock usage is well below 50%. Generally, future blocks should always have some spare capacity. Since blocks may temporarily exceed capacity limits, execution must be asynchronous from consensus. For details on the asynchronous execution proposal, see the APE article.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News