Interpreting Starknet's Smart Contract Model and Native AA: A Maverick Technical Mastermind

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

Interpreting Starknet's Smart Contract Model and Native AA: A Maverick Technical Mastermind

This article will briefly outline Starknet's technical approach and mechanism design, starting from its smart contract model and native AA.

Authors: Shew & Faust, Geeker Web3

Advisor: CryptoNerdCn, core developer of the Starknet ecosystem, founder of WASM Cairo — a browser-based Cairo development platform

Abstract

Starknet’s key technical features include the Cairo language optimized for ZK proof generation, native-level account abstraction (AA), and a smart contract model that separates business logic from state storage.

Cairo is a general-purpose ZK language capable of implementing smart contracts on Starknet as well as developing more traditional applications. Its compilation process introduces Sierra as an intermediate language, enabling frequent iteration of Cairo without changing the underlying bytecode—changes are simply propagated to the intermediate layer. Additionally, Cairo’s standard library includes many fundamental data structures required for account abstraction.

Starknet smart contracts separate business logic from state data. Unlike EVM chains, Cairo contract deployment consists of three stages: "compile, declare, deploy." Business logic is declared in a Contract class, while contract instances containing state data can be associated with this class and invoke its code.

This smart contract architecture supports code reuse, state reuse, storage layering, garbage contract detection, and lays the groundwork for future implementation of storage leasing and transaction parallelization. While the latter two features are not yet live, the design of Cairo contracts creates the necessary conditions for them.

Starknet only has smart contract accounts—there are no externally owned accounts (EOAs). It supports native-level account abstraction from day one. Its AA approach draws partial inspiration from ERC-4337, allowing users to choose highly customizable transaction processing workflows. To prevent potential attack vectors, Starknet has implemented numerous countermeasures, making significant contributions to the evolution of the AA ecosystem.

Main Text

Following the launch of Starknet’s token, STRK has gradually become an essential element in the eyes of Ethereum observers. This Ethereum Layer 2 project, long known for being “eccentric” and “indifferent to user experience,” has quietly cultivated its own niche within the predominantly EVM-compatible Layer 2 landscape—like a reclusive hermit indifferent to worldly affairs.

Its disregard for usability was so extreme that it even opened an “electronic beggar” channel on Discord, drawing criticism from bounty hunters. Amid accusations of being “out of touch,” Starknet’s deep technical expertise suddenly seemed “worthless,” as if only UX and wealth creation mattered. The line from *The Temple of the Golden Pavilion*—“Not being understood became my only pride”—perfectly encapsulates Starknet’s self-image.

Yet setting aside these controversies and viewing things purely from the perspective of code-savvy developers’ “technical taste,” Starknet and StarkEx—pioneers among ZK Rollups—are treasures in the eyes of Cairo enthusiasts. For some full-chain game developers, Starknet and Cairo represent nothing less than the entirety of web3, far surpassing Solidity or Move. The biggest gap today between “tech geeks” and “users” stems largely from insufficient understanding of Starknet.

Driven by curiosity about blockchain technology and a desire to uncover Starknet’s value, this article aims to clarify its technical architecture and mechanism design by focusing on Starknet’s smart contract model and native account abstraction, showcasing the traits of this “misunderstood lone wolf” to a broader audience.

A Brief Introduction to the Cairo Language

In the following sections, we will focus on Starknet’s smart contract model and native account abstraction, explaining how native AA is achieved. After reading this, you’ll also understand why mnemonic phrases from different wallets cannot be used interchangeably in Starknet.

Before diving into native account abstraction, let’s first get familiar with Cairo, the language uniquely developed for Starknet. In its evolution, Cairo went through an early version called Cairo0, followed by a modern version. The modern syntax resembles Rust and is in fact a general-purpose ZK language. Beyond writing smart contracts on Starknet, it can also be used to develop general-purpose applications.

For example, you could use Cairo to build a ZK identity verification system—a program that runs on your own server without relying on the Starknet network. Any application requiring verifiable computation can potentially be implemented in Cairo. And Cairo may currently be the most efficient programming language for generating ZK proofs.

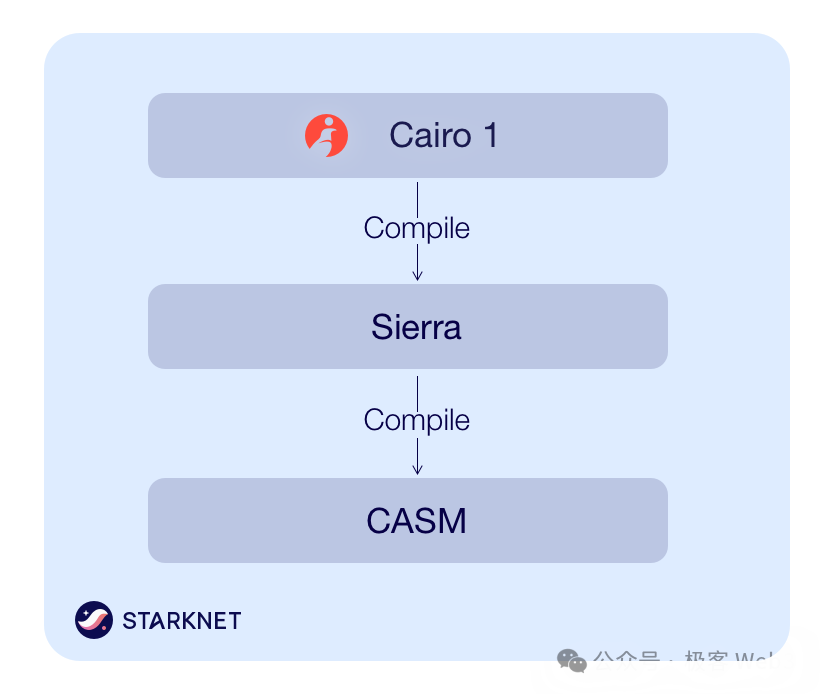

From a compilation standpoint, Cairo uses an intermediate representation (IR) approach. As shown in the diagram below, Sierra serves as an intermediate form during the compilation of Cairo code. Sierra is then compiled into lower-level binary code called CASM, which runs directly on Starknet nodes.

Introducing Sierra as an intermediate step allows new features to be added to Cairo easily—most changes can be confined to Sierra, without altering the underlying CASM code, sparing node operators from frequent client updates. Thus, Cairo can evolve rapidly without modifying Starknet’s base-layer logic. Moreover, Cairo’s standard library already includes many basic data structures needed for account abstraction.

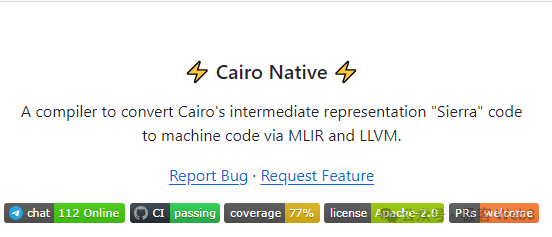

Other innovations in Cairo include a theoretical proposal known as Cairo Native, which aims to compile Cairo into hardware-specific machine code. This would allow Starknet nodes to execute smart contracts without relying on the CairoVM interpreter, dramatically improving execution speed [still theoretical, not yet implemented].

Starknet Smart Contract Model: Separation of Code Logic and State Storage

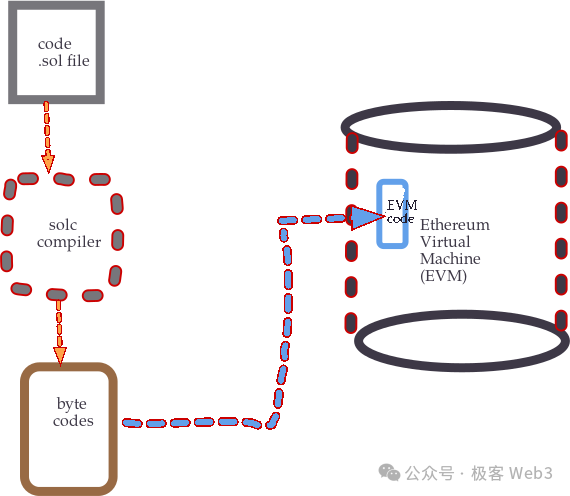

Unlike EVM-compatible chains, Starknet has made groundbreaking innovations in its smart contract design—many of which support native AA and prepare for future transaction parallelization. It's important to note that on traditional blockchains like Ethereum, smart contract deployment typically follows a “compile-then-deploy” pattern. For ETH smart contracts:

1. Developers write their smart contract locally and use an editor to compile Solidity code into EVM bytecode, which can be directly interpreted and executed by the EVM;

2. The developer initiates a contract deployment transaction, uploading the compiled EVM bytecode onto the Ethereum chain.

(Image source: not-satoshi.com)

While Starknet also follows the idea of “compile before deploy,” deploying contracts as CASM bytecode supported by CairoVM, it differs significantly from EVM chains in terms of contract invocation and state storage models.

To be precise, Ethereum smart contracts = business logic + state information. For instance, a USDT contract implements functions like Transfer and Approval, and also stores the balance states of all USDT holders. This tight coupling of code and state creates multiple issues—it hinders DApp contract upgrades and state migration, complicates transaction parallelization, and represents a heavy technical burden.

To address this, Starknet improved its state storage method. In its implementation, DApp business logic and asset state are completely decoupled and stored separately. The benefits are clear: the system can quickly identify redundant or duplicated code deployments. Here's why:

Ethereum smart contracts = business logic + state data. If several contracts have identical logic but different state data, their hashes differ. As a result, the system cannot easily detect redundancy or identify “garbage contracts.”

In contrast, Starknet separates code and state data, allowing the system to determine code duplication based solely on the hash of the logic portion, since identical code produces identical hashes. This helps prevent redundant deployments and conserves node storage space.

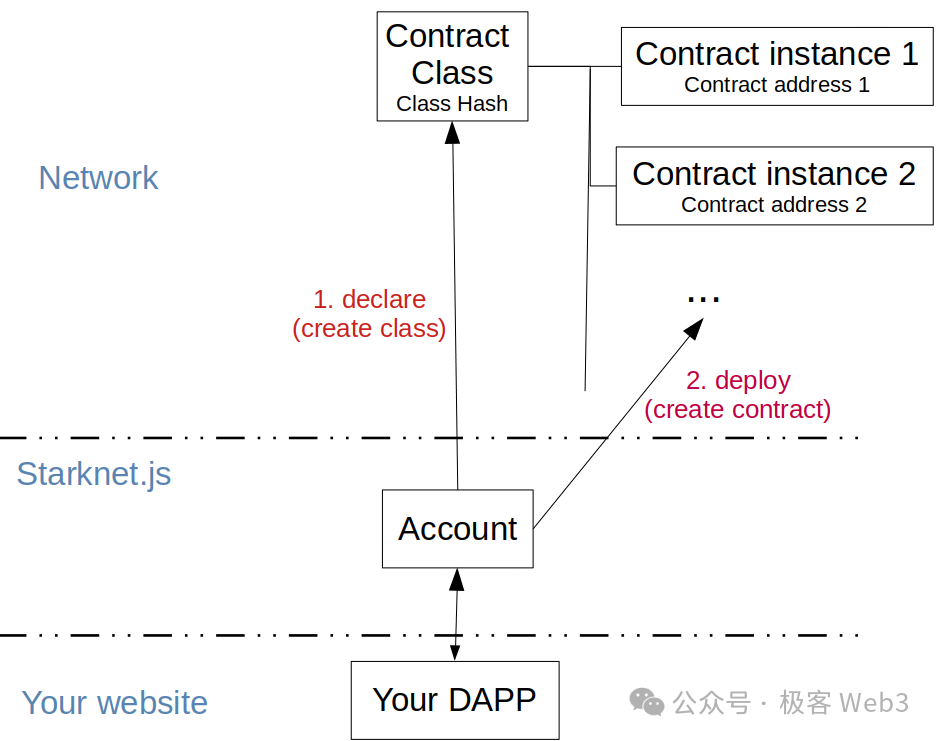

In Starknet’s smart contract system, deployment and usage involve three distinct phases: "compile, declare, deploy." When an asset issuer wants to deploy a Cairo contract, the first step is compiling the written Cairo code into Sierra and low-level CASM bytecode locally.

Next, the deployer submits a “declare” transaction, publishing the CASM bytecode and Sierra intermediate code on-chain as a Contract Class.

(Image source: Starknet official website)

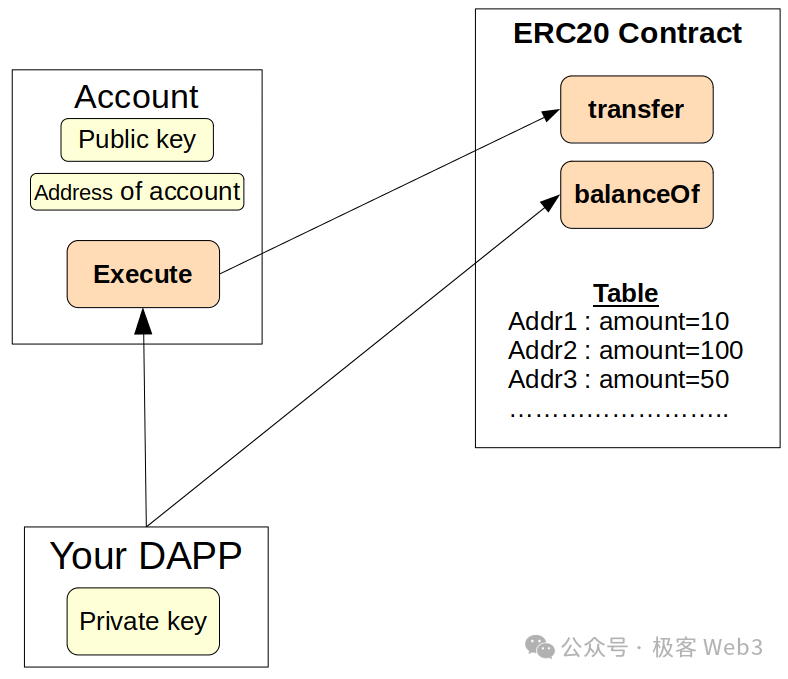

Then, if you want to use the functions defined in this asset contract, you can initiate a “deploy” transaction via a DApp frontend to create a Contract instance linked to the Contract Class. This instance holds the actual state data. Users can later call functions from the Contract Class to modify the state of the instance.

Anyone familiar with object-oriented programming should easily grasp the distinction between Class and Instance in Starknet. The Contract Class declared by developers contains only business logic—a callable set of functions—but no actual state data. It has a “soul” but no “body.”

Only when a user deploys a specific Contract instance does the asset become “embodied.” To change the state of this “entity”—for example, transferring tokens to someone else—you can directly invoke the pre-written functions in the Contract Class. This process resembles “instantiation” in traditional object-oriented languages (though not exactly the same).

By separating smart contracts into Classes and Instances, decoupling logic from state brings Starknet several advantages:

1. Facilitates storage layering and "storage leasing"

Storage layering allows developers to store data in custom locations, such as off-chain. Starknet plans to integrate with DA layers like Celestia, enabling DApp developers to store data off-chain. For example, a game might keep critical asset data on Starknet mainnet while storing other data on Celestia. This customizable choice of DA layer based on security needs is named “Volition” by Starknet.

Storage leasing means users must continuously pay rent for the storage space they occupy. Theoretically, the more chain space you use, the more ongoing fees you should pay.

In the Ethereum smart contract model, ownership is ambiguous—making it unclear whether the contract deployer or token holders should pay “rent,” which is why storage leasing hasn’t been implemented. Instead, only a one-time fee is charged at deployment—a flawed economic model.

In contrast, Starknet—as well as Sui, CKB, and Solana—has clearer ownership definitions in its contract model, facilitating future storage fee collection [Starknet hasn’t launched storage leasing yet, but plans to implement it].

2. Enables true code reuse and reduces garbage contract deployment

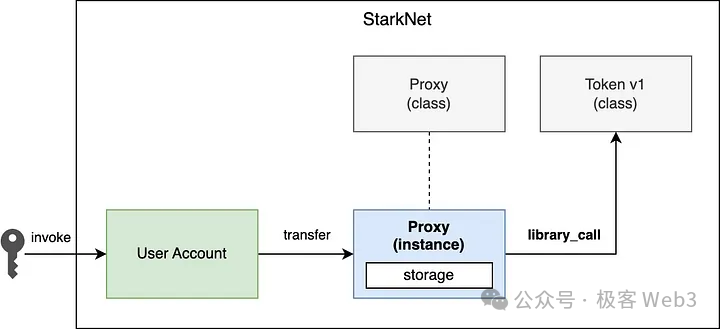

We can declare a generic token contract as a class on-chain, allowing everyone to reuse its functions to deploy their own token instances. Contracts can also directly invoke code from the class, achieving effects similar to Solidity’s Library feature.

Additionally, Starknet’s contract model aids in identifying “garbage contracts,” as previously explained. With better code reuse and garbage detection, Starknet can significantly reduce on-chain data volume and alleviate node storage pressure.

3. True contract “state” reuse

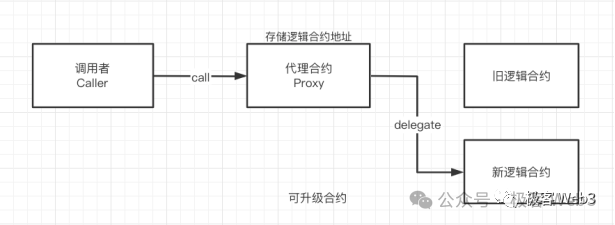

Smart contract upgrades primarily involve updating business logic. In Starknet’s case, logic and state are naturally separated. A contract instance can upgrade its logic simply by switching to a new Contract class—no need to migrate state data. This form of upgrade is more thorough and native compared to Ethereum’s approach.

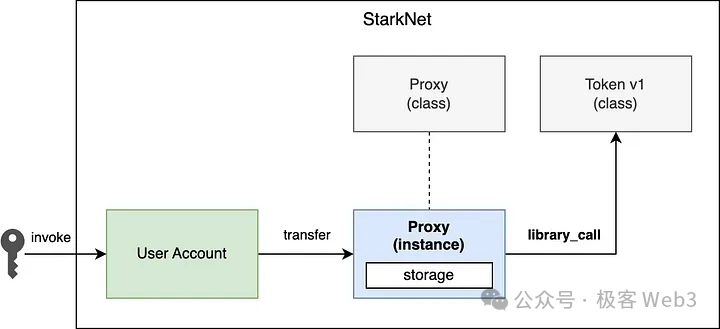

On Ethereum, changing business logic usually requires delegating it to a proxy contract. Updating the proxy changes the main contract’s behavior, but this method is neither clean nor truly native.

(Image source: wtf Academy)

In certain cases, if an old Ethereum contract is abandoned entirely, its state cannot be directly migrated—creating major headaches. Cairo contracts avoid this issue entirely by reusing existing state seamlessly.

4. Enables transaction parallelization

To maximize transaction parallelism, it’s crucial to store individual users’ states separately—a principle evident in Bitcoin, CKB, and Sui. Achieving this requires decoupling business logic from state data. Although Starknet hasn't deeply implemented transaction parallelization yet, it remains a major future goal.

Starknet’s Native AA and Account Contract Deployment

Actually, the concepts of account abstraction and AA were invented by the Ethereum community. Many newer blockchains don’t distinguish between EOAs and smart contract accounts—they avoided Ethereum’s account model pitfalls from the start. Under Ethereum’s rules, an EOA controller must hold ETH on-chain to send transactions, lacks flexible authentication methods, and struggles to implement customized payment logic. Some even argue Ethereum’s account design is fundamentally anti-user.

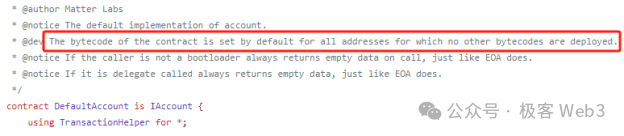

Observing chains like Starknet or zkSync Era that emphasize “native AA”, we see clear differences: they unify account types—only smart contract accounts exist on-chain, with no concept of EOAs from the beginning. (zkSync Era automatically deploys a default contract on new accounts to mimic EOA behavior, easing Metamask compatibility.)

Starknet doesn’t prioritize direct compatibility with tools like Metamask. When users first use a Starknet wallet, a dedicated contract account is automatically deployed—essentially instantiating the contract discussed earlier. This instance links to a pre-deployed contract class provided by the wallet provider and can invoke functions defined in that class.

Now let’s discuss an interesting point: during the STRK airdrop, many noticed Argent and Braavos wallets weren’t compatible—importing Argent’s mnemonic into Braavos failed to recover the corresponding account. This happens because Argent and Braavos use different algorithms to generate accounts, leading to different addresses from the same mnemonic.

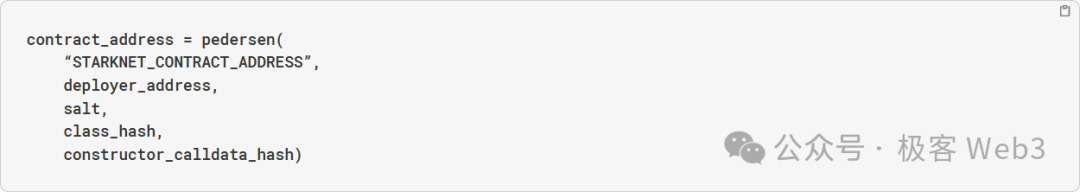

Specifically, in Starknet, new contract addresses are deterministically computed using the following formula:

Here, pedersen() is a hash function suitable for ZK systems. Generating an account involves feeding specific parameters into the pedersen function to produce a hash—the resulting account address.

The image above shows the parameters used in computing a new contract address on Starknet. deployer_address refers to the “contract deployer’s” address and can be empty—even without an existing Starknet account, you can still deploy a new contract.

salt is a random number used as input to prevent address collisions. Using this formula, users can calculate their contract address before deployment. Starknet allows contract deployment even without an existing account. The process works as follows:

1. Determine which Contract class your instance will link to. Use its hash as one initialization parameter, compute the salt, and derive your target contract address;

2. Once you know where the contract will be deployed, send a small amount of ETH to that address to cover deployment costs. Typically, this ETH is bridged from L1 to Starknet;

3. Initiate the contract deployment transaction.

In reality, all Starknet accounts are deployed this way, but most wallets hide these details—users aren’t aware of the process, giving the impression that the account is instantly created upon receiving ETH.

This approach causes compatibility issues—different wallets generate different addresses. Wallets can only be interoperable if they meet all of the following conditions:

-

Use the same private key derivation, public key generation, and signature algorithms;

-

Have identical salt calculation procedures;

-

Implement no fundamental differences in the smart contract class logic;

In the earlier example, both Argent and Braavos use ECDSA signatures, but their salt computation methods differ—leading to different account addresses from the same mnemonic.

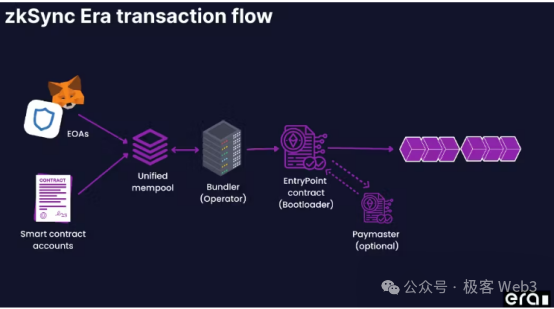

Returning to account abstraction: Starknet and zkSync Era move core transaction processing steps—such as identity verification (signature checking) and gas fee payment—outside the “base layer” of the chain. Users can customize how these logics are implemented within their own accounts.

For example, you can deploy a custom digital signature verification function in your Starknet smart contract account. When a Starknet node receives your transaction, it invokes the custom transaction handling logic defined in your on-chain account—offering far greater flexibility.

In Ethereum’s design, however, identity verification and similar logic are hardcoded into node clients and cannot natively support custom account functionality.

(Diagram by a Starknet architect illustrating native AA: transaction validation and gas eligibility checks are moved to on-chain contracts. The base VM can invoke user-defined or specified functions.)

According to officials from zkSync Era and Starknet, this modular account design takes inspiration from EIP-4337. However, unlike Ethereum, zkSync and Starknet merged account types from the start, unified transaction formats, and adopted a single entry point for all transactions. Ethereum, burdened by legacy constraints and aiming to avoid hard forks, adopted EIP-4337 as a “roundabout solution.” But this results in separate processing flows for EOAs and 4337 accounts—awkward and bloated compared to native AA.

(Image source: ArgentWallet)

Currently, Starknet’s native account abstraction isn’t fully mature. In practice, Starknet AA supports custom signature verification algorithms. However, for gas payment customization, Starknet currently only accepts ETH and STRK as gas tokens and does not yet support third-party gas sponsorship. Therefore, Starknet’s progress on native AA can be described as “theoretical framework largely complete, practical implementation still underway.”

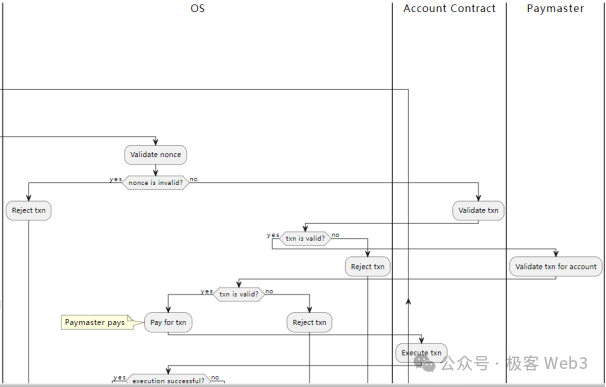

Since Starknet only has smart contract accounts, every stage of transaction processing considers the impact of account contracts. When a transaction enters a Starknet node’s mempool, it undergoes validation including:

-

Checking the correctness of the transaction’s digital signature, invoking the custom verification function defined in the sender’s account contract;

-

Verifying whether the sender’s account balance can cover gas fees.

Note: using a custom signature verification function in an account contract opens up potential attack vectors. Because the mempool performs signature validation without charging gas (charging gas here would create worse attack scenarios), malicious users could define extremely complex verification functions in their contracts and flood the network with transactions—all triggering expensive validations—effectively exhausting node computational resources.

To prevent this, Starknet imposes the following restrictions:

-

A single user has a cap on the number of transactions allowed per unit time;

-

Custom signature verification functions in Starknet account contracts are subject to complexity limits. Overly complex functions won’t execute. Starknet sets a gas consumption ceiling for verification functions—transactions exceeding this threshold are rejected. Additionally, verification functions cannot call other contracts.

The Starknet transaction flowchart is as follows:

Notably, to further accelerate transaction validation, Starknet node clients have directly built-in support for Braavos and Argent wallet signature verification algorithms. When nodes detect transactions from these two major Starknet wallets, they use the native verification logic embedded in the client—similar to caching—to reduce validation time.

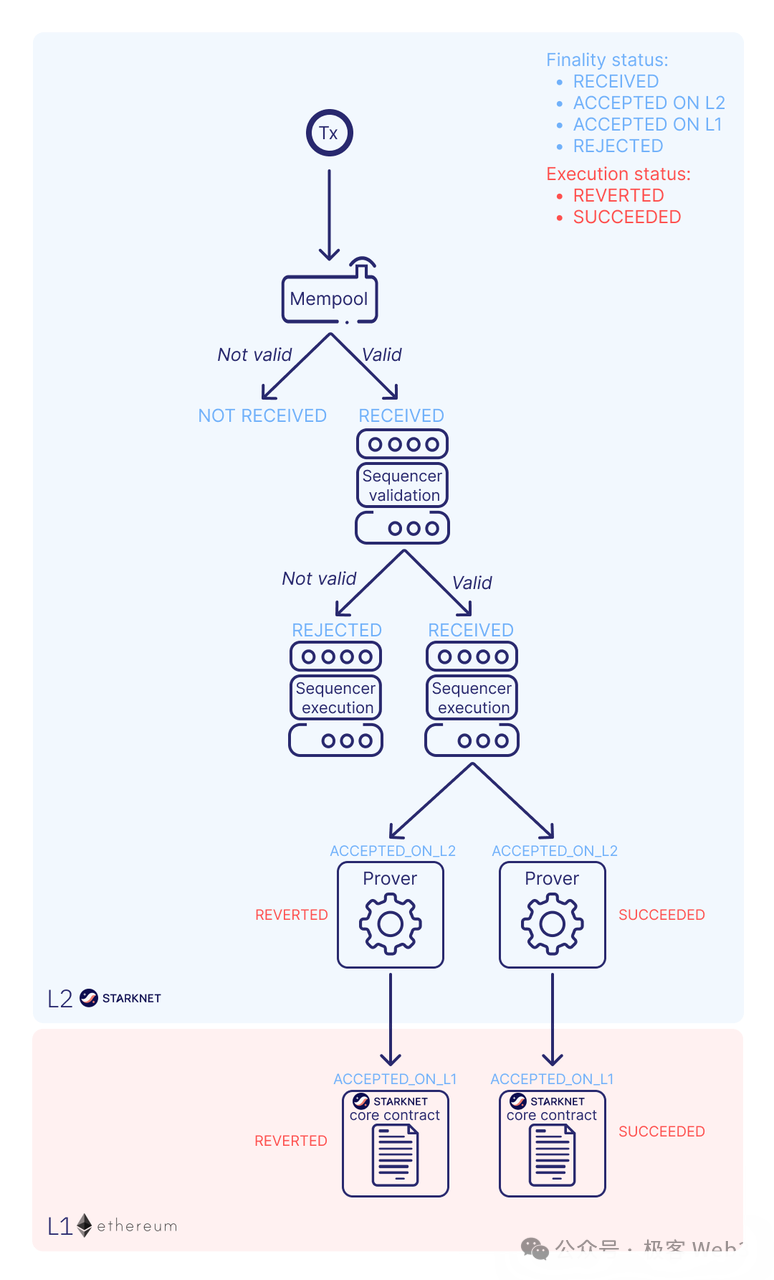

After passing mempool validation, transactions undergo deeper verification by the sequencer, which then batches and forwards valid transactions to the ZK proof generator. At this stage, even failed transactions incur gas fees.

However, those familiar with Starknet’s history may recall that early versions did not charge gas for failed transactions. The most common failure scenario was users attempting to transfer more ETH (e.g., 10 ETH) than they held (e.g., 1 ETH). Such transactions obviously fail due to logical errors, though the outcome isn’t known until execution.

Previously, Starknet didn’t charge gas for such failures. These costless erroneous transactions wasted node computation and enabled DDoS-style attacks. Charging gas for failed transactions seems straightforward, but implementation is actually quite complex. The release of the new Cairo1 language was largely driven by the need to solve this gas charging problem.

We know ZK proofs are validity proofs—failed transactions produce invalid outcomes and leave no on-chain output. Attempting to use a validity proof to prove that a transaction failed and produced no output sounds paradoxical—and indeed, it’s unworkable. Previously, Starknet simply excluded failed transactions from proof generation since they couldn’t produce outputs.

The Starknet team later devised a smarter solution: developing a new contract language, Cairo1, ensuring “every transaction instruction produces an on-chain output.” At first glance, this implies no transaction ever fails. But in reality, most failures stem from bugs causing execution interruption.

Achieving uninterrupted execution that always returns output is difficult, but there’s a simple workaround: even when a transaction fails due to a logic error, make it return an output—specifically, a False value indicating the operation didn’t succeed.

Crucially, returning False still counts as producing an output. In Cairo1, regardless of logic errors or interruptions, every instruction generates an on-chain output—either a correct result or a False error indicator.

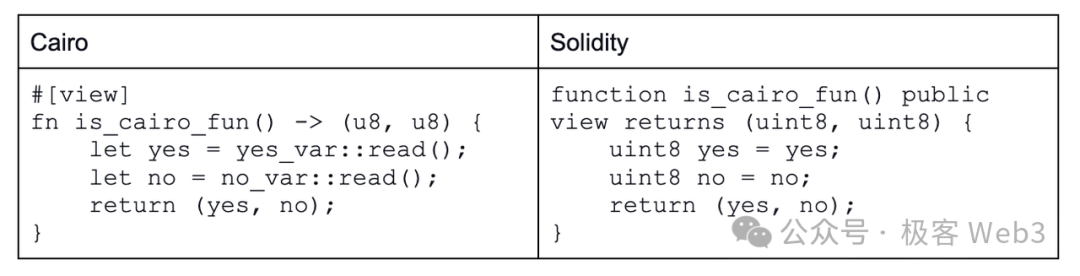

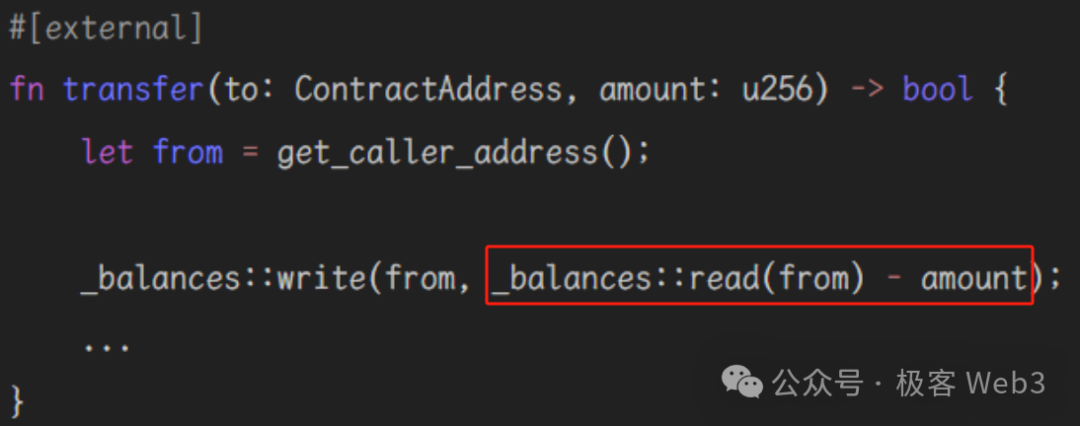

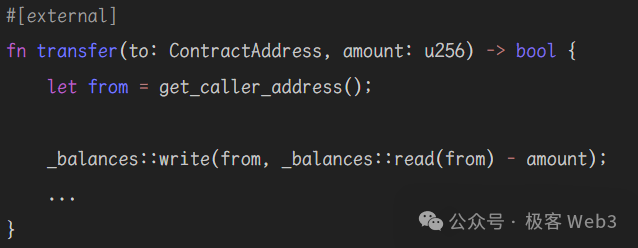

For example, consider the following code snippet:

Here, _balances::read(from) - amount may underflow and cause an error, halting execution without leaving any on-chain record. Rewriting it as shown below ensures an output is returned even upon failure, preserving it on-chain. Visually, it appears as if every transaction successfully leaves an output—making uniform gas charging perfectly reasonable.

Overview of Starknet AA Contracts

Considering some readers may have a programming background, we briefly present the interface of a Starknet account abstraction contract:

In the above interface, __validate_declare__ validates user-initiated declare transactions, __validate__ handles general transaction validation (primarily checking signature correctness), and __execute__ executes the transaction. Notably, Starknet contract accounts natively support multicall (batched calls). Multicall enables interesting use cases—for instance, bundling three DeFi actions:

-

Approve a token for use by a DeFi contract

-

Trigger logic in the DeFi contract

-

Revoke approval after execution

Of course, since multicalls are atomic, more advanced use cases exist—such as executing arbitrage trades.

Conclusion

Starknet’s primary technical features include the Cairo language optimized for ZK proof generation, native-level account abstraction (AA), and a smart contract model that separates business logic from state storage.

Cairo is a general-purpose ZK language usable for both Starknet smart contracts and traditional applications. Its compilation pipeline introduces Sierra as an intermediate language, enabling frequent Cairo iterations without modifying the lowest-level bytecode—changes are applied only to the intermediate layer. Cairo’s standard library also incorporates many foundational data structures required for account abstraction.

Starknet smart contracts separate business logic from state data. Unlike EVM chains, Cairo contract deployment involves three stages: “compile, declare, deploy.” Business logic resides in the Contract class, while state-holding Contract instances associate with the class and invoke its code.

This smart contract architecture promotes code reuse, state reuse, storage layering, and garbage contract detection. It also enables future implementation of storage leasing and transaction parallelization. While the latter two are not yet active, the Cairo contract architecture provides the necessary foundation.

Starknet only has smart contract accounts—no EOAs—supporting native-level account abstraction from inception. Its AA design partially adopts ideas from ERC-4337, allowing highly customizable transaction processing. To mitigate potential attack risks, Starknet has implemented various safeguards, contributing valuable insights to the development of the AA ecosystem.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News