Gavin Wood: What lessons have we learned in moving from Polkadot 1.0 to JAM?

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

Gavin Wood: What lessons have we learned in moving from Polkadot 1.0 to JAM?

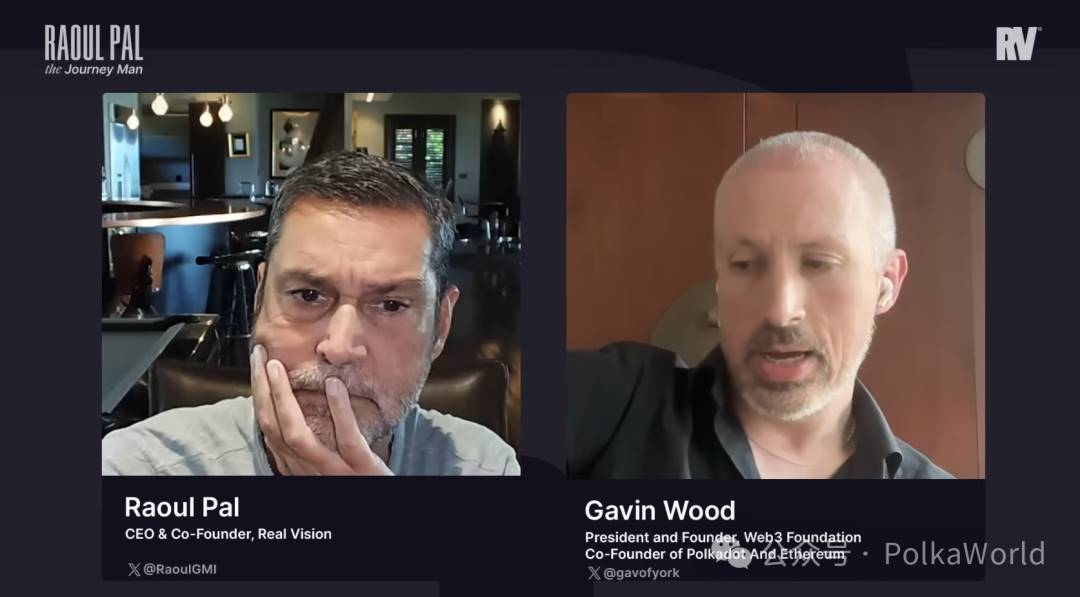

Gavin shared some interesting stories from before he started Ethereum, as well as reflections and lessons learned during the journey from Polkadot 1.0 to JAM.

Compiled by: PolkaWorld

A few months ago, Gavin was interviewed by Raoul Pal. While not the latest video, some of the insights Gavin shared are still worth understanding! As usual, we'll split it into two parts. This is the first half of that video! Gavin primarily shares some interesting stories from before he started Ethereum, along with reflections and lessons learned during the journey from Polkadot 1.0 to JAM.

Let’s start with some key quotes!

-

Ethereum wasn’t just a simple copy of Bitcoin; it was genuinely trying to push boundaries. At the time, no one had started building it yet, and I knew I could build something entirely new from scratch.

-

In a way, Polkadot represents my attempt at making a further technical contribution to the Web3 space. The idea originated from thinking about what Ethereum 2.0 might look like.

-

If you can't scale a system by increasing individual node performance, then you need to go for "horizontal scaling".

-

I firmly believe that having a single security umbrella is the most rational approach. I think decentralized security models are meaningless.

-

The biggest change in my thinking on Polkadot relates to what I call "persistent state fragmentation". We shouldn't make persistent fragmentation a fixed pattern—we should adopt more flexible, temporary forms of fragmentation.

-

The definition of “parachains” can now be greatly relaxed—any chain that fits into this universal JAM model of the “world computer” can be considered a parachain.

-

The core issue we’re discussing is scalability—not just increasing data throughput, but also improving how efficiently data is processed within the system. Only by boosting these capabilities by several orders of magnitude can we truly support meaningful real-world use cases and migrate existing Web2 applications to Web3.

-

The goal of JAM is to let you run nearly ordinary computer code directly—not smart contracts—without complex gas optimizations, enabling code upload and execution at minimal cost, thus attracting users.

-

Once Web3 becomes a legitimate alternative to Web2, sufficient markets will open up—even if blockspace costs approach zero, there will still be enough value to pay validators maintaining the network.

-

If blockspace is cheap enough—nearly free—the question shifts from access barriers and use cases to whether they're truly useful, and whether there are users and markets.

Keep reading for more!

Gavin's Story Before Ethereum

Raoul Pal: Your personal journey is truly remarkable. If you don’t mind, could you take us back—share your story? Starting before Ethereum, how did you first get involved in this field?

Gavin: I’ve always been deeply interested in economics and game theory. I studied computer science at university, but my first encounter with Bitcoin was around February or March 2013, when I read an article about Amir Taaki, a Bitcoin developer who identified as a cypherpunk and crypto-anarchist. He seemed like a fascinating figure, so I thought it would be interesting to meet him and hear his worldview. I was already interested in contributing to Bitcoin projects, so I emailed him. He replied, and we met in a derelict building in London—my first time visiting such a place. He introduced me to several people in the Bitcoin community, starting with Mihai Alisie and his girlfriend Roxana. She was sitting on a mattress—the room looked like an office, and the abandoned building was actually an old office block. I was surprised our first meeting happened in such an environment.

Later, Mihai became my co-founder on Ethereum, so although it was a strange first encounter, it turned out to be significant. He also introduced me to others in the London Bitcoin scene who were running Bitcoin cash exchange points. Through them, I stayed connected and eventually met Vitalik. I read Vitalik’s Ethereum whitepaper at the end of 2013 and began writing code.

Raoul Pal: When you first saw the Ethereum whitepaper and spoke with Vitalik, what made you feel this was a breakthrough moment? What made Ethereum more appealing than Bitcoin? After all, you could have stayed within the Bitcoin ecosystem, but you chose Ethereum.

Gavin: I certainly could have stayed in the Bitcoin ecosystem. Ultimately, when building something, you look for where you can create the most impact. Bitcoin already had a team, a client, and a community—it was already mature. Ethereum, however, didn’t seem like a mere clone of Bitcoin; it was genuinely trying to push boundaries. No one had started building it yet, and I knew I could build something entirely new from the ground up. At that point, I realized my expertise and value would be greater in helping build something completely new, and my skills would be better utilized in such a project.

Were You Surprised by Ethereum's Success?

Raoul Pal: Were you surprised by its success, or did you always believe this would be the next big breakthrough? After all, many other blockchains were emerging at the time—were you surprised by Ethereum’s success?

Gavin: If I were truly surprised, I probably wouldn’t have committed so strongly. You can never fully predict outcomes—success depends not just on whether a project is slightly or significantly better, but also on whether it adds specific functionalities and other factors. But yes, I did have a strong sense at the time. The real reason came when I traveled to Miami in January 2014 and met several co-founders, experiencing the Bitcoin community atmosphere firsthand. It was a major Bitcoin conference in Miami, Florida, filled with energy and parties. Vitalik invited me to a hackathon there, saying we’d finish coding. I flew to Miami expecting to work with the dev team for a week, only to find it was more like a party house—with me being the only one writing code. Still, I felt the excitement and enthusiasm.

There were other projects too—if you remember, Mastercoin was popular then, promoting itself as “Bitcoin, but with financial tools.” Counterparty was similar, targeting different applications. NXT was a proof-of-stake (PoS) version of Bitcoin. To me, it was clear Ethereum offered far more potential than these nascent blockchain projects.

Combined with that excitement, and seeing the other co-founders as key driving forces, I believed Ethereum had a real chance to become very big.

Why Did You Create Polkadot?

Raoul Pal: So what prompted you to launch your own blockchain? I recall someone mentioning Polkadot to me around 2012 or 2013—at a roundtable I hosted, before your official launch. They said it was important, but I didn’t understand “interoperability” at all. I thought it sounded good, but had no clue what they meant. Could you walk me through the story of creating Polkadot? How did the idea form in your mind? Let’s discuss this journey—where you were right, where you were wrong, and where things are headed.

Gavin: In a way, Polkadot was my attempt to make a further technical contribution to the space. The idea emerged from thinking about what Ethereum 2.0 might look like, or how a successor system to Ethereum should function. I always believed it would likely be a multi-chain architecture with many different chains. But before Polkadot took shape, I imagined all those chains would perform the same function—like Ethereum, all EVM chains operating similarly to Ethereum 1.0.

I envisioned a top-level chain—similar to Ethereum’s Beacon Chain, which we later called the Relay Chain in Polkadot—to ensure all sub-chains operated correctly. But then I realized maybe these chains didn’t need to do the same thing—perhaps it would even be simpler if they didn’t. These chains could differ, focusing on specialized domains—what we now commonly call app-specific chains.

Even though functionally different, they’d share the same security, enabling easy interaction and interoperability. Interoperability has multiple meanings, sometimes causing confusion. But in this context, I mean secure interactions under a shared security framework, allowing direct, causally linked communication between chains.

Of course, we've learned many lessons along the way. Ultimately, it’s been an experiment. We weren’t sure how valuable this level of interoperability would be compared to Ethereum’s synchronous composability—where contracts can call each other and respond instantly. But tracing back Polkadot’s origin, the core idea was placing diverse chains under one security umbrella, each focused on its own domain.

Raoul Pal: You foresaw the multi-chain world long before others realized it. That idea faced heavy skepticism because many believed in a single EVM world or a single Bitcoin world, but you anticipated a future with multiple coexisting chains.

Gavin: For me, it wasn’t ideological—it stemmed from the necessity of scalability. Everyone was asking how to scale, because while Ethereum was great, it couldn’t scale. So the question became: How do we scale the system? The answer: parallelization. You can scale vertically, like Solana attempts—using faster validators with tighter connections. But you eventually hit a bottleneck, especially if you want to preserve Web3’s accessibility. Validator hardware demands grow, raising entry barriers.

If you can’t scale by boosting individual node performance, you must go for horizontal scaling. This is classic Silicon Valley thinking—scaling comes from distributing workload across multiple nodes. Break tasks into smaller pieces and assign them to different nodes. That’s Polkadot’s core principle.

Initially, I didn’t think each workload segment needed to become a permanent, independently state-maintained chain. Tasks could be allocated flexibly and temporarily. However, the fundamental idea of splitting and distributing workloads to scale the network is unavoidable.

What Was Gavin Thinking From Polkadot 1.0 to JAM?

Raoul Pal: How have your assumptions changed? What drove you to take new actions? Because you're continuously building a new world with Polkadot—what makes you believe you can break boundaries again?

Gavin: The biggest shift involves what I call "persistent state fragmentation". I firmly believe a single security umbrella is the most rational setup. Decentralized security models make no sense to me. Cosmos’ original model—and still largely today—is based on decentralized security, though they’re now exploring shared security without fully achieving it. I don’t see that as wise. I believe in the Ethereum and Polkadot model: a unified security umbrella enabling parallelization within that framework.

The change lies in how we approach parallelization structurally. The main difference between my view of Polkadot 1.0 and JAM (as outlined in the recent grey paper) is that Polkadot 1.0 assumes "persistent fragmentation"—multiple blockchains, each with their own state, operating in isolation. Though secured uniformly, they run independently, with separate collator sets and state transition rules. They can send messages via XCM, but it’s coarse-grained compared to fine-grained contract interactions on Ethereum. I realized this severely limits composability and viable blockspace usage models. Therefore, we shouldn’t treat persistent fragmentation as a default. Instead, we should embrace more flexible, temporary fragmentation.

So rather than permanently fragmenting state at blockchain boundaries, we instead re-shard the overall state roughly every six seconds. Arbitrary sharding raises implementation questions—we’re exploring possible solutions. But our approach avoids hardcoding fragmentation at the protocol layer. Instead, we re-partition dynamically based on new use cases, block by block.

Essentially, we’re transforming the Polkadot Relay Chain—which was originally designed to provide security and message passing between different blockchain ecosystems—into something resembling a "world computer", a ubiquitous multi-core virtual machine capable of hosting programs. Our goal is for these programs to handle not only large volumes of data but also intensive computation.

Raoul Pal: For those who may not grasp your point, could you illustrate it with a concrete use case? When you envision solving a problem or a future state, you must have a mental model. How do you think about how this technology will be used? What changes will it bring? How does it unlock new blockchain use cases? Can you walk us through your thinking?

Gavin: A simple example frequently discussed in the Polkadot ecosystem is SPREE—an early concept I later generalized as Accords. You can think of an Accord as a smart contract governing how two independent blockchains interact. Although different parts of an Accord may run on separate chains, they know they belong to the same system. It’s somewhat like international law—once a blockchain commits to an Accord, it can’t arbitrarily opt out. It either complies or exits. And as long as it complies, it can interact securely with other compliant chains.

Consider a “token transfer Accord” as an example. It ensures that when I send you tokens, I only mint new ones after you’ve burned yours. Likewise, I know you’ll mint new tokens after I burn mine. This means two blockchains can interact directly via bilateral messaging without trusting the chains themselves to enforce the transaction.

Raoul Pal: Is this limited to the Polkadot ecosystem, or can it apply to any chain?

Gavin: It currently applies only to chains secured by Polkadot—those within the Polkadot ecosystem. However, the definition of “parachain” has now greatly expanded—any chain that integrates into this universal “world computer” model can be considered a parachain. So we can now imagine—more clearly than before—that although Polkadot wasn’t initially designed for ZK Rollups, its architecture is general enough. While勉强 achievable, this model makes Polkadot’s computational model far more universal.

This leads us to ask: If it’s not a traditional parachain but a ZK Rollup, can Polkadot still verify all its transactions for correctness? Then, can it do more—like properly ordering transactions, enforcing Accord compliance, or ensuring correct message delivery?

How Will JAM Drive Application Development and Adoption?

Raoul Pal: In real-world use cases, how will this capability drive application development and adoption in Web3?

Gavin: I approach this from a low-level perspective, not focusing much on specific applications. I could tell you what supply chain management could achieve, but the exact use case isn’t the point. The key is whether the system can support applications at a certain scale. Suppose you want to track global supply chains and log all freight data—this involves massive amounts of information. Thousands of ships, millions of shipping containers. You need to ingest all this data into a large state machine and perform sufficient computation to make the application meaningful in reality.

The core issue we’re discussing is scalability. Current blockchains aren’t well-suited for such demands. We need to increase both data volume and computational capacity—not just input/output throughput, but processing efficiency. Only by improving these capabilities by several orders of magnitude can we support meaningful real-world use cases and migrate existing Web2 applications to Web3.

This is precisely the goal of JAM—a blueprint designed to handle globally scaled transaction data.

When Will JAM Launch?

Raoul Pal: When will JAM launch? I know this is usually a hard question, but what’s your internal roadmap? Roughly how long will it take?

Gavin: It’s always hard to say. Let me give an analogy: I reserved a Tesla Roadster in October 2017, immediately after seeing it. I thought, “Take my money—it’ll be delivered in two years!” Six years later, I’ve heard nothing. I expected to get the car before Polkadot launched, but clearly I was way off. Now I hope to get the Tesla before JAM launches—but who knows?

Actually, I’m loosely modeling the timeline on Ethereum’s. I published the Ethereum yellow paper about ten years ago, and it took roughly six to seven months from that point until the protocol was finalized and released. After auditing, minor adjustments were made, and it launched in summer 2015—July or August. So we might aim for a similar timeline with JAM.

The core components of the JAM protocol are mostly complete. I’m now finalizing additional sections for the grey paper, expected to wrap up in the next week or two. Then comes community review, research team analysis, prototyping, and audits. But I believe the major questions around JAM have largely been resolved.

How to Compete for Users?

Raoul Pal: Once JAM launches, the main challenge for blockchains will be user adoption. How do you plan to tackle this? Many chains are competing fiercely for attention—even paying users to generate on-chain activity. How do you address this, since it’s not just technical scaling but business-level scaling?

Gavin: My basic view is that current blockchains don’t offer high-quality, decentralized blockspace suitable for most real-world applications. Usually, you pay high fees and often need to buy ETH through an exchange just to use Ethereum. I know efforts are underway to improve infrastructure, but realistically, this won’t change much in the short term. A key reason is insufficient scalability—blockspace isn’t cheap enough.

Blockspace needs to become nearly free, with scalability so high that you can run almost ordinary computer code directly on-chain. That’s exactly what JAM is designed for. JAM aims to let you run nearly standard computer code—not smart contracts—without complex gas optimizations, uploading and executing code at minimal cost to attract users. That’s JAM’s central mission.

How Does the Network Accumulate Value?

Raoul Pal: So it’s like cloud computing—over time, digital resources eventually become nearly free. Cloud computing is a perfect example: once expensive, now affordable unless used at scale. But if everything becomes nearly free, how does value accumulate in the ecosystem? Unless you have massive volume, like AWS in cloud computing. How do you see this?

Gavin: I believe as blockspace costs approach zero, new applications and markets will emerge. Applications previously uneconomical become viable when transaction costs near zero. My goal is to reach a stage where you no longer need to buy cryptocurrency via an exchange to transact on-chain. Currently, almost every blockchain action requires holding crypto first, severely limiting market and use case expansion. I hope to eventually overcome this, but that requires massive scalability—JAM is the first step toward that extreme scalability.

I believe once Web3 becomes a legitimate alternative to Web2, sufficient markets will open—so even if blockspace costs approach zero, there will still be enough value to pay validators maintaining the network. Thus, ultimate scale will ensure blockspace retains enough value to sustain the entire ecosystem.

How Many New Entrants Can Join This Field?

Raoul Pal: I’ve been thinking—when we look at infrastructure technologies like 3G or fiber optics, they eventually reach massive overcapacity, followed by consolidation and clearer direction. Do you see blockchain heading that way? Because we haven’t solved many issues yet, and blockchains aren’t perfect—they can’t solve everything. When do you think we’ll reach that phase of overcapacity?

Gavin: I think we might face a situation similar to the energy sector—and I’m not even sure we truly have excess energy capacity. Humanity is still fighting for energy. Creating low-quality blockspace is easy—just set up an isolated, insecure private chain and you have it immediately. But building high-quality, well-connected blockspace isn’t simple.

Raoul Pal: I’m also thinking about the ability of new entrants to join, not necessarily about overcapacity in blockspace. I agree—cheaper, faster blockspace enables more use cases, and eventually the whole internet may depend on it. That part is fine. But the key question is: how much innovation or how many new people can still enter? Or will it stop at some point—say, when new projects can no longer get funding?

Gavin: My point is, if blockspace is cheap enough—nearly free—the issue shifts from entry barriers and use cases to whether they’re truly useful, and whether there are users and markets. If there’s a market, it’s like launching a website and running servers on AWS. If server costs are low enough that you can easily serve your first hundred users, and users are eager for your new service, then even if energy remains scarce or AWS becomes expensive serving billions, it doesn’t matter—because the market exists, and users are willing to pay.

Therefore, I don’t think newcomers will face major hurdles in use cases or applications, as long as there aren’t artificial constraints. Of course, one issue with Polkadot 1.0 is the 50 parachain slots—limited in number. Once full, no matter how good your use case, you must wait or join a Crowdloan to compete, which is difficult. That’s a lesson we learned from Polkadot—entry barriers must be lowered, not just for new apps, but for new users too. That’s exactly what we’re trying to solve with JAM.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News