Hack VC: A Look at Popular Blockchain Privacy Technologies

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

Hack VC: A Look at Popular Blockchain Privacy Technologies

The combined application of technologies remains a field worthy of in-depth exploration.

Author: Duncan Nevada

Compiled by: TechFlow

The transparent ledgers of cryptographic technology have fundamentally changed our understanding of trusted systems. As the old adage goes: "Don't trust, verify." Transparency is precisely what enables us to do so—when all information is public, any forgery can be promptly detected. However, this transparency also reveals limitations in usability. Indeed, some data should be public—such as settlements, reserves, reputation (and perhaps even identity)—but we certainly don’t want everyone’s financial and health records exposed alongside their personal details.

Privacy Needs in Blockchain

Privacy is a fundamental human right. Without privacy, there can be no freedom or democracy.

Just as early internet required encryption technologies like SSL to enable secure e-commerce and protect user data, blockchain requires robust privacy technologies to fully realize its potential. SSL allowed websites to encrypt data in transit, ensuring sensitive information such as credit card numbers wouldn't be intercepted by malicious actors. Similarly, blockchain needs privacy to safeguard transaction details and interactions while maintaining the integrity and verifiability of the underlying system.

Privacy on blockchain is not only about protecting individual users; it's crucial for enterprise adoption, compliance with data protection regulations, and opening up new design spaces. No company wants every employee to see others’ salaries, or competitors to rank and poach their most valuable customers. Moreover, industries such as healthcare and finance have strict regulatory requirements around data privacy—blockchain solutions must meet these standards to become viable tools.

A Framework for Privacy-Enhancing Technologies (PETs)

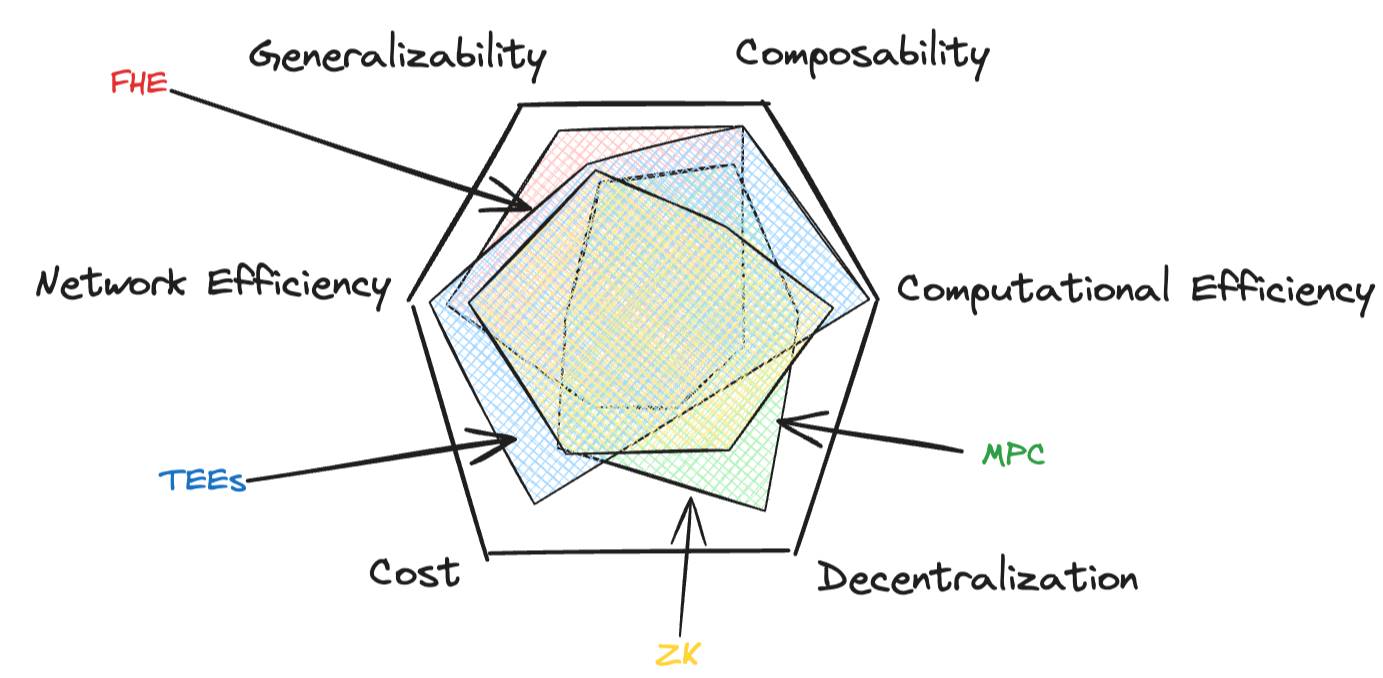

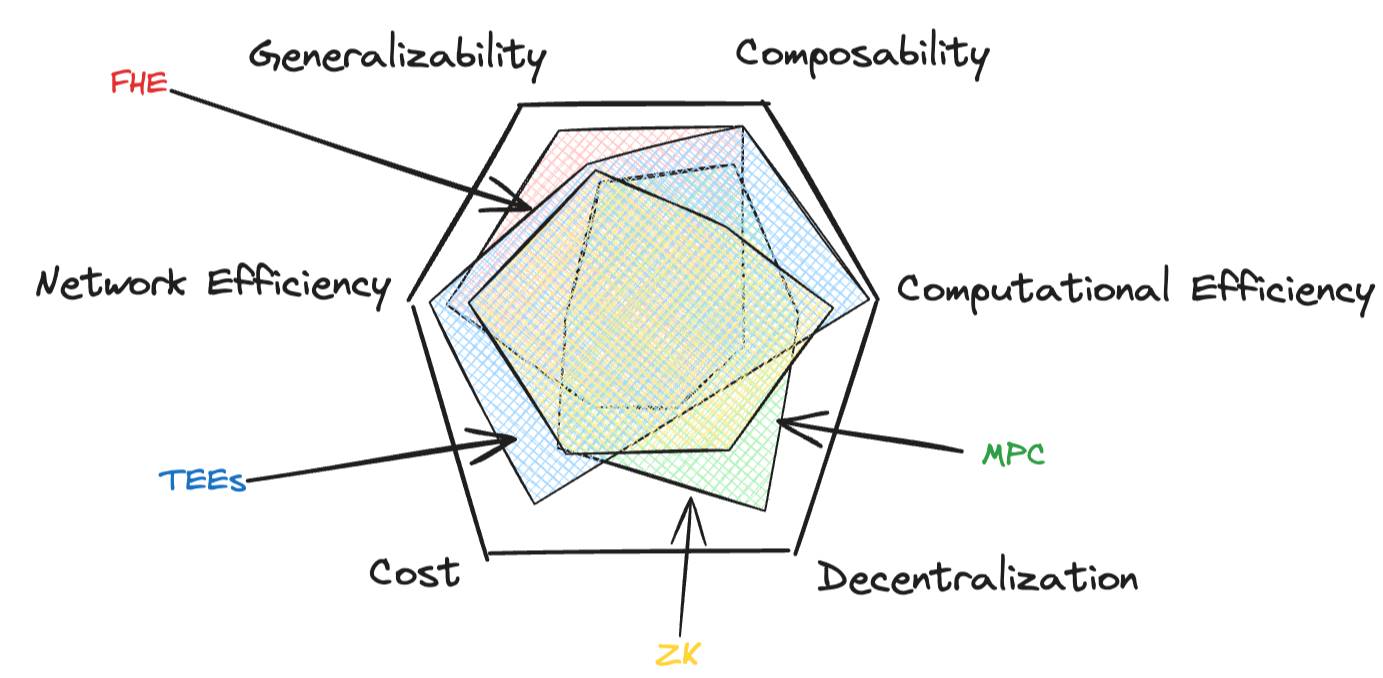

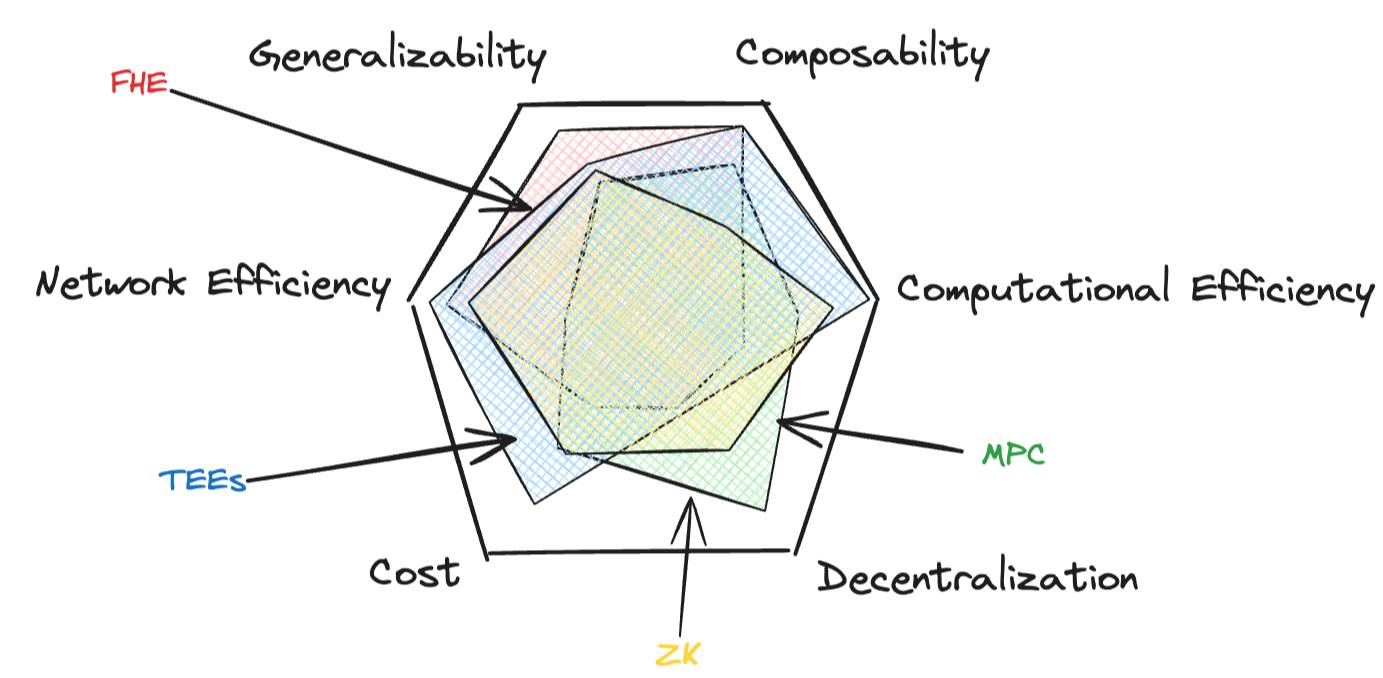

As the blockchain ecosystem evolves, several key Privacy-Enhancing Technologies (PETs) have emerged, each with unique advantages and trade-offs. These include Zero-Knowledge Proofs (ZK), Multi-Party Computation (MPC), Fully Homomorphic Encryption (FHE), and Trusted Execution Environments (TEE), spanning six critical axioms:

-

Generality: The applicability of a solution across diverse use cases and computations.

-

Composability: How easily the technology can be combined with others to mitigate weaknesses or unlock new design possibilities.

-

Computational Efficiency: The efficiency with which the system performs computations.

-

Network Efficiency: The system’s scalability as participants or data volume increases.

-

Decentralization: The degree to which the security model is distributed.

-

Cost: The practical cost of achieving privacy.

Just as blockchains face a trilemma between scalability, security, and decentralization, simultaneously achieving all six properties is challenging. However, recent advancements and hybrid approaches are pushing the boundaries of what’s possible, bringing us closer to comprehensive, affordable, and efficient privacy solutions.

Now that we have this framework, let’s briefly survey the landscape and explore the future outlook for these PETs.

Overview of Privacy-Enhancing Technologies

Here, I’d like to offer some definitions. Note: I assume you’re actively reading *Dune* and viewing everything through the lens of melange!

Zero-Knowledge (ZK) is a technology that allows verification that a computation has occurred and produced a result, without revealing the inputs.

-

Generality: Medium. Circuits are highly application-specific but improving via hardware abstraction layers (e.g., Ulvatana and Irreducible) and general-purpose interpreters (e.g., Nil's zkLLVM).

-

Composability: Medium. It works well when isolating trusted provers, but in networked settings, the prover must see all raw data.

-

Computational Efficiency: Medium. With real-world ZK applications like Leo Wallet launching, novel implementations are delivering exponential improvements in proving speed. Further progress is expected as client adoption grows.

-

Network Efficiency: High. Recent advances in folding techniques introduce significant potential for parallelization. Folding is essentially a more efficient way to build iterative proofs, enabling construction upon prior work. Nexus is a project worth watching.

-

Decentralization: Medium. In theory, proofs can be generated on any hardware, though GPUs are currently preferred. While hardware is becoming more standardized, economic-layer decentralization can be enhanced via AVSs like Aligned Layer. Inputs remain private only when combined with other technologies (see below).

-

Cost: Medium.

- High initial implementation costs due to circuit design and optimization.

- Moderate operational costs—proof generation is expensive but verification is efficient. A major cost factor is proof storage on Ethereum, which can be mitigated using data availability layers (e.g., EigenDA) or AVSs.

-

Dune analogy: Imagine Stilgar needs to prove to Duke Leto that he knows the location of the spice fields without revealing where they are. Stilgar takes a blindfolded Leto on a sandworm flight, circling above the fields until the cabin fills with the sweet scent of cinnamon, then returns him to Arrakeen. Leto now knows Stilgar can find the spice—but not how.

Multi-Party Computation (MPC) is a technique that allows multiple parties to jointly compute a result without revealing their individual inputs to one another.

-

Generality: High, given the variety of specialized MPC variants (e.g., secret sharing).

-

Composability: Medium. While MPC is secure, composability decreases with computational complexity, which introduces greater network overhead. However, MPC excels at handling private inputs from multiple users—a relatively common use case.

-

Computational Efficiency: Medium.

-

Network Efficiency: Low. As the number of participants increases, required network communication grows quadratically. Companies like Nillion are working to solve this. Erasure coding or Reed-Solomon codes (splitting data into fragments and storing them separately) can reduce errors, though this isn’t traditional MPC.

-

Decentralization: High. Although collusion among participants may compromise security.

-

Cost: High.

- Implementation costs range from medium to high.

- Operational costs are high due to communication overhead and computational demands.

-

Dune analogy: Imagine the Great Houses of the Landsraad need to confirm sufficient collective spice reserves to support one another in times of need, but none wish to disclose their individual stockpiles. The first house sends a message to the second, adding a large random number to its actual reserve. The second house adds its own reserve, and so on. When the first house receives the final sum, it subtracts the initial random number to reveal the true total spice reserve.

Fully Homomorphic Encryption (FHE) allows computations to be performed directly on encrypted data without decrypting it first.

-

Generality: High.

-

Composability: High for single-user inputs. For multi-party private inputs, it must be combined with other technologies.

-

Computational Efficiency: Low. Although ongoing optimizations at both mathematical and hardware levels are progressing rapidly—this could be a game-changing breakthrough. Zama and Fhenix are doing excellent work in this area.

-

Network Efficiency: High.

-

Decentralization: Low. Due to high computational demands and complexity, though decentralization may approach ZK levels as the tech matures.

-

Cost: Very High.

- High implementation costs due to complex cryptography and stringent hardware requirements.

- High operational costs due to intensive computation.

-

Dune analogy: Imagine a device similar to a Holtzman shield, but for digital data. You place encrypted data inside the shield, activate it, and hand it to a Mentat. The Mentat performs calculations without ever seeing the raw data. Upon completion, they return the shield. Only you can deactivate it and view the result.

Trusted Execution Environments (TEE) are secure areas within a computer processor that allow sensitive operations to run in isolation from the rest of the system. TEEs are unique in relying on silicon and metal rather than polynomials and curves. Thus, despite being powerful today, their improvement may theoretically lag due to reliance on costly hardware.

-

Generality: Medium.

-

Composability: High. Though potentially vulnerable to side-channel attacks, reducing overall security.

-

Computational Efficiency: High. Approaching server-side performance—so much so that NVIDIA’s new H100 chipset series includes TEE support.

-

Network Efficiency: High.

-

Decentralization: Low. Limited to specific chipsets (e.g., Intel SGX), making them susceptible to side-channel attacks.

-

Cost: Low.

- Low implementation cost if existing TEE hardware is used.

- Low operational cost due to near-native performance.

-

Dune analogy: Imagine the Spacing Guild Heighliner’s navigation chamber. Even the Guild’s own navigators cannot see or interfere with what happens inside. A navigator enters the chamber, performs the complex calculations needed for foldspace travel, while the chamber itself ensures all operations remain private and secure. The Guild provides and maintains the chamber, guaranteeing its integrity, yet cannot observe or intervene in the navigator’s internal work.

Practical Use Cases

Perhaps instead of battling spice cartels, we should focus on ensuring sensitive data—like key material—remains private. To ground this in reality, here are practical use cases for each technology.

Zero-Knowledge Proofs (ZK) are ideal for verifying that a process produced the correct output. When combined with other technologies, ZK becomes a powerful privacy tool, but alone it sacrifices trustlessness and functions more like data compression. We typically use ZK to verify state equivalence—for example, comparing an “uncompressed” Layer 2 state with a block header published on Layer 1—or proving someone is over 18 without revealing personally identifiable information.

Multi-Party Computation (MPC) is commonly used in key management—private keys or decryption keys—and can be combined with other technologies. It's also applied in distributed random number generation, lightweight secure computation tasks, and oracle aggregation. In general, any scenario requiring lightweight aggregation across multiple non-colluding participants is well-suited for MPC.

Fully Homomorphic Encryption (FHE) is suitable for performing simple, general-purpose computations on data that computers cannot see—such as credit scoring, Mafia-style logic in smart contract games, or ordering transactions without revealing their contents.

Finally, Trusted Execution Environments (TEE) are best for more complex operations—if you're willing to trust the hardware. For instance, TEEs are the only feasible solution for private foundation models (large language models used within enterprises or institutions in finance, healthcare, or national security). As the only hardware-based solution, mitigating TEE drawbacks will theoretically be slower and more costly than with other technologies.

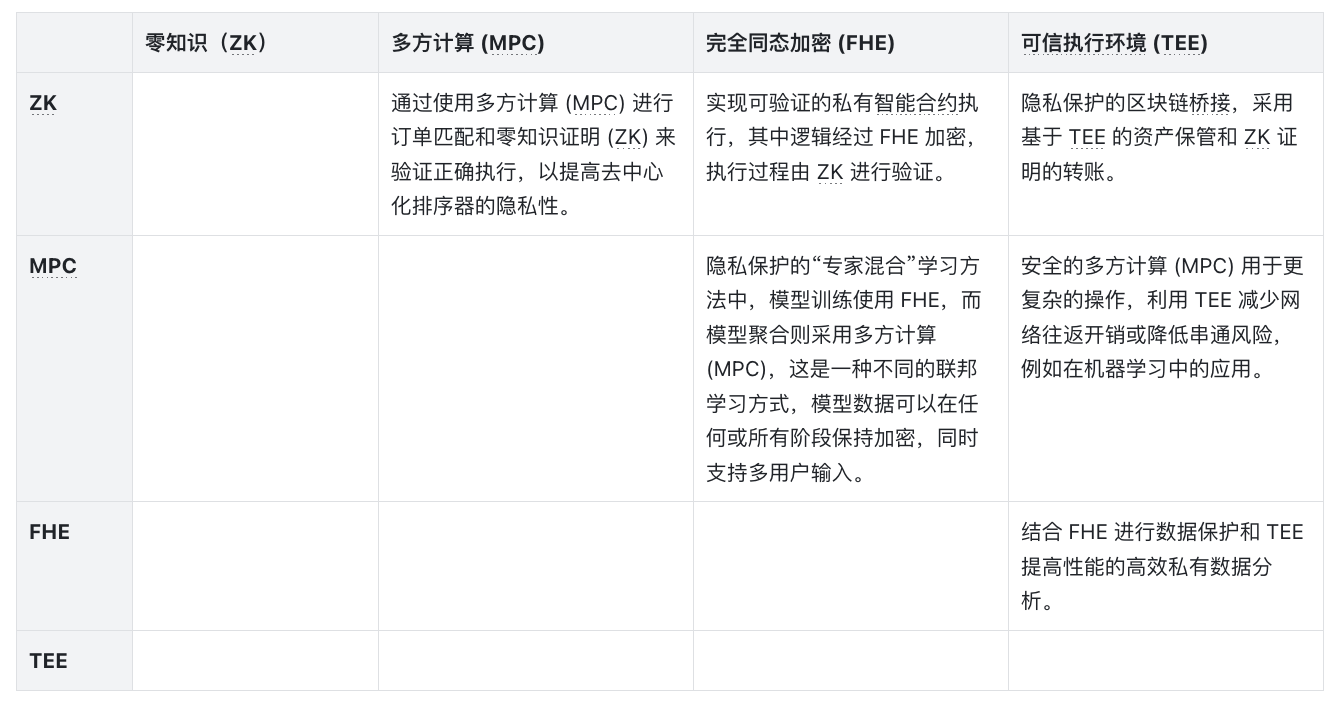

In Between

Clearly, no perfect solution exists, nor is one likely to emerge. Hybrid approaches are exciting because they can leverage the strengths of one technology to offset the weaknesses of another. The table below illustrates some design spaces unlocked by combining different methods. Practical implementations vary widely—combining ZK and FHE might require finding compatible curve parameters, while integrating MPC and ZK may involve optimizing setup parameters to reduce network round trips. If you're building and looking to discuss, hopefully this sparks some inspiration.

In short, high-performance, generalizable privacy technologies can unlock countless applications—from gaming (a nod to Baz’s brilliant writing in Tonk), governance, fairer transaction lifecycles (Flashbots), identity (Lit), non-financial services (Oasis), to collaboration and coordination. This is also why we’re excited about Nillion, Lit Protocol, and Zama.

Conclusion

In summary, Privacy-Enhancing Technologies (PETs) hold immense potential, yet we’re still in the early stages of exploring what’s possible. While individual technologies may mature over time, combining them remains a rich frontier for innovation. Applications will be tailored to specific domains, and as an industry, we still have much work ahead.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News