Understanding Blackbird: How the "Eat to Earn" Model Is Disrupting the Dining Industry—Can Crypto Applications Profit in Real-World Businesses?

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

Understanding Blackbird: How the "Eat to Earn" Model Is Disrupting the Dining Industry—Can Crypto Applications Profit in Real-World Businesses?

The quality of the dining experience, and therefore its profitability, depends on its business model.

Author: Not Boring by Packy McCormick

Translation: TechFlow

Blackbird was the first on-chain app I ever used, but it didn’t feel like one. It felt more like a restaurant app. I used it to discover restaurants and earn loyalty points. Starting today, I can use it to automatically pay my bill—no need to check the tab—using a credit card, debit card, or Blackbird’s $FLY token.

At the end of last year, I wrote that as on-chain product barriers decrease, more great entrepreneurs would build on-chain products. Blackbird is the best example I’ve seen. I’d use this app whether it was on-chain or off-chain; it’s also a tool restaurants use even if they’ve never heard of crypto or don’t particularly like it, because it helps them make money. But it’s also an app whose vision for restaurants and customers couldn’t exist without crypto.

Running a restaurant is extremely difficult. 60% of restaurants fail within their first year. Those that survive do so on razor-thin margins. Yet restaurants bring vibrancy, comfort, and familiarity to cities and communities. We want them to survive and thrive.

So this piece will dive into Blackbird, the challenges of running a restaurant, and how, in the right entrepreneur’s hands, crypto can help restaurants improve their business.

This isn’t a sponsored deep dive—I’m not an investor, though a16z crypto (where I serve as an advisor) is. I’m just a fan and user, a New Yorker hoping my favorite restaurants stick around long enough to buy me a free drink.

Let’s go!

Blackbird

The restaurant industry exists in a fundamental paradox: it’s a business centered on hospitality designed to make each customer feel special, yet it’s also a volume business that needs to serve as many people as possible to stay profitable.

If you watched Season 3 of The Bear, you saw this paradox portrayed with extreme realism. It’s Richie versus Computer. Five-star hospitality versus cold, hard numbers.

Richie and Computer, The Bear

Blackbird is what happens when Richie and Computer merge: using data to elevate personalized hospitality.

Blackbird is a loyalty and payments platform built for the restaurant industry. For customers, it offers the chance to “be regulars anywhere.” The company aims to solve this core paradox, merging good hospitality with good business.

At its core, Blackbird is trying to scale the “regular” experience across multiple venues—the feeling of being recognized, valued, treated like an old friend. In doing so, it hopes to reshape the economics of an entire industry in dire need of reshaping.

Restaurants are unique in many ways. Collectively, they’re powerful: restaurants generated over $1 trillion in sales in the U.S. last year, nearly 5% of GDP. But individually, each restaurant operates under a famously difficult business model: 60% fail in their first year, 80% within five years. In 2023, 38% of restaurants reported no profit.

The reasons for this difficulty are varied and intertwined, creating a massive knot of problems. Rent keeps rising—you suddenly realize your favorite bar has turned into a Chase Bank. Labor is hard to recruit and retain, kitchens are chaotic, inventory expires. Those Instagram kids book only the cheapest dishes just to take photos. Then a new, trendier restaurant opens down the street, and all the young people stop coming. More people opt for delivery, and delivery services take big cuts from your revenue. Reservations no-show, leaving precious tables empty. When they do show up, reservation platforms also take a cut, as do payment processors. When the dust settles, if you’re still alive, you’re left with average margins of just 4%, down from 20% twenty-five years ago, and little capital left to reinvest in the high-quality service and photogenic dining environments people now expect. It’s amazing any survive at all.

Ben Leventhal understands this better than almost anyone, and he wants to fix it.

Ben Leventhal, founder of Blackbird

I love a book called The City We Became by N.K. Jemisin, where she personifies each NYC borough. Manhattan is a young, flashy, multiracial guy; Brooklyn is a middle-aged Black woman, former rapper; the Bronx is a street-smart Afro-Latina woman; Queens is an Indian immigrant math student; Staten Island is a sheltered, somewhat racist white woman.

If Jemisin were to personify New York’s restaurant scene, she’d choose Ben Leventhal.

“Ben is so New York in a way that’s hard to describe,” Jay Drain Jr., investment partner at a16z crypto who led the Blackbird investment, told me. “He looks like he belongs in a restaurant.”

Ben grew up in New York, attended Horace Mann, the school that inspired Gossip Girl. After a brief college stint, he returned to New York and dove into the intersection of food and tech.

In 2005, he founded Eater, a restaurant recommendation blog. Before Eater, people relied on printed guides that were outdated the moment they hit shelves or snobby professional critics reviewing fancy places. Eater embraced the internet and succeeded. He sold it to Vox Media in 2013.

In 2014, he founded Resy, a reservation platform. Before Resy, people used OpenTable, a 1998 product designed for desktop computers. “Smartphones came and went, but OpenTable didn’t really update its core concept,” he said on the Serious Eats podcast. Resy embraced mobile and succeeded. He sold it to American Express in 2019.

After working for several years at AmEx, a $170 billion payments and loyalty giant, Ben started discussing his next move with some friends. One of them was Fred Wilson, a partner at Union Square Ventures and an early Coinbase investor. Ben had an idea for a payments and loyalty product for restaurants, and Fred encouraged him to consider building it on-chain. So he did, with USV and Shine Capital co-leading an $11 million raise, and Blackbird was born.

As you read those last few paragraphs, you might notice a few themes.

First, the product progression mirrors the customer journey: discovering where to eat (Eater), making reservations (Resy), enjoying the experience, paying, and returning (Blackbird).

Second, each product embraced a new technology platform first. Eater replaced print with internet blogs; Resy replaced desktop (and paper scraps, spreadsheets, and emails) with mobile apps. Blackbird is replacing fragmented loyalty programs and high-fee payment systems with crypto.

In this way and others, Blackbird is running the Ben Leventhal Playbook, but with some new twists.

There’s an important difference here, though. While Ben sold Eater and Resy to centralized companies, that’s not the plan for Blackbird. Instead, as the company gradually decentralizes, ownership of the network will reside primarily with the restaurants themselves. “Overall, the restaurant industry should own about half the network,” Ben told me.

This is one of the new possibilities enabled by crypto, but Blackbird works because it’s not a crypto app. It’s a restaurant platform and consumer app built by restaurant people, using crypto and other necessary tools only to make restaurants more profitable, help them understand customers better, and build a healthier industry.

When I asked Ben what he wanted people to know about the Blackbird story, he said they’re excited about the industry’s long-term outlook.

“We’re only a few core breakthroughs away from a better industry.”

This is a deep dive into the industry and those key breakthroughs.

How to Think About Blackbird

There are several different ways to think about Blackbird. They interconnect, but it’s worth analyzing them separately before weaving them together.

One way to think about Blackbird is from the industry’s perspective: as a tool to help restaurants improve unit economics through payments, loyalty, and customer insights.

Another way to think about Blackbird is from the customer’s perspective: as a way to discover places to eat and get personalized experiences commensurate with their loyalty.

A third way to think about Blackbird is as a business: as an on-chain version of American Express, similar in many ways but different in key aspects.

A fourth way to think about Blackbird is as a blockchain network: as a decentralized platform capable of creating and distributing new forms of value within the restaurant ecosystem and beyond.

It encompasses all of these, but to understand them, we need to first understand the restaurant business.

The Restaurant Business

Restaurants are something we’re reluctant to view as businesses. Businesses require trade-offs, and we wish restaurants didn’t have to make them. We want to walk into a restaurant and enjoy great food and service every time because, from our perspective, a restaurant is an experience. It’s a rare chance to be taken care of, treated like nobility, a small indulgence.

But restaurants are businesses, and their business models directly affect the level of service provided.

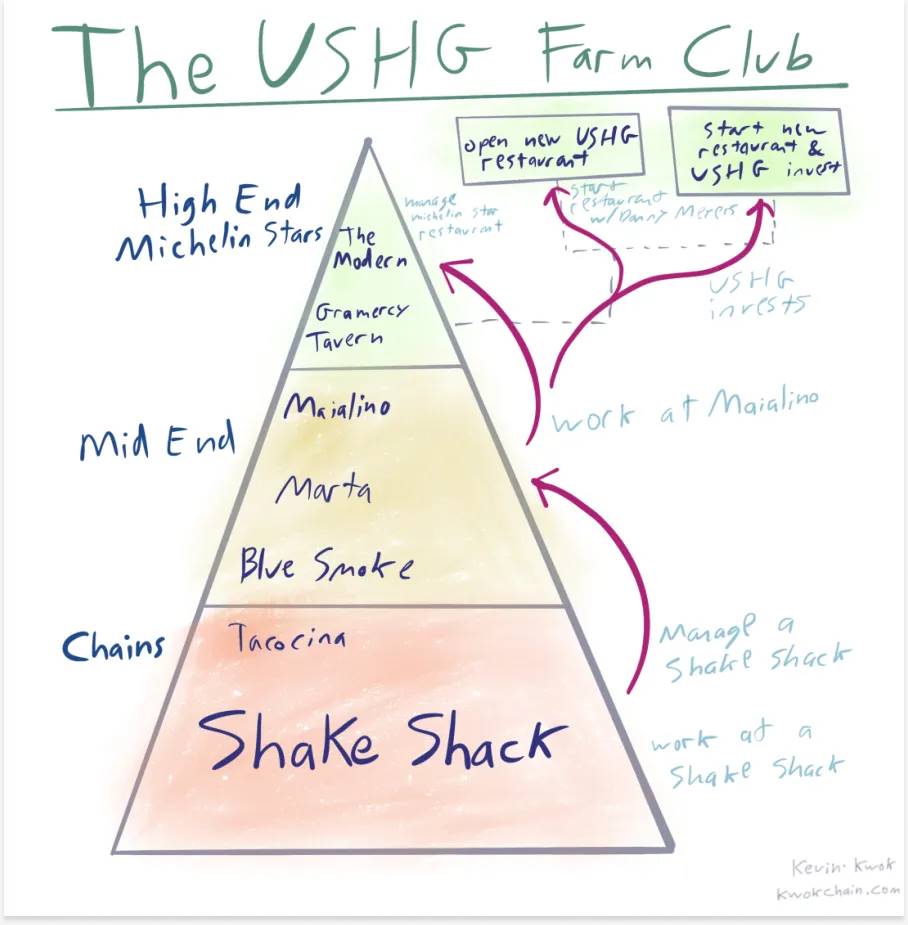

In 2019, Kevin Kwok wrote Aligning Business Models to Markets, using Danny Meyer’s Union Square Hospitality Group (USHG) as a primary example.

USHG is undoubtedly a success story in the restaurant industry. Meyer built Union Square into what it is today. The Modern, Union Square Cafe, Manhatta, Gramercy Tavern, and ci siamo have long been favorites among New Yorkers. Shake Shack, spun out of USHG, has a market cap of $3.4 billion. Its consistency stands out in such a challenging industry.

How does Danny do it? As Kwok explains: “In his business memoir Setting the Table, Meyer attributes his immense success to a relentless focus on employees, which leads to differentiated service.”

So Kwok asks: “If Danny Meyer’s employee-first approach is so effective, why haven’t more restaurant groups adopted it faster?” and answers: “Providing high-level service is a choice that must be supported by the business model.”

I strongly recommend reading the whole piece. Long story short, high-level service requires investing in employee training, and training employees is expensive—most restaurants can’t afford it because turnover ranges from 50% to 110%. Once you pay someone for training, they leave. USHG, however, can afford to train employees because the group operates everything from fast-casual to fine dining, giving employees clear career paths. You can start behind the counter at Shake Shack and eventually manage The Modern.

Kevin Kwok, Aligning Business Models to Markets

Because employees stay longer, USHG can invest more in training them, which creates differentiated service, making USHG restaurants exceptional, allowing the group to keep opening new restaurants and create more career opportunities for employees.

The point is, the quality of the restaurant experience—and therefore profitability—depends on its business model.

But Kwok wonders: why is this model thriving now, when the same argument could have been made at any point in the hundreds of years of restaurant history?

In the past, people chose local restaurants largely because there weren’t many options. The restaurant industry used to be supply-driven. Now, consumers have hundreds of choices and dozens of internet sources to discover them, making it far more important to be somewhere people want to return to. The restaurant industry is now demand-driven. As Kwok writes:

These shifts toward the demand side of the industry have made restaurants more focused on service quality. Customers can go wherever they want, so excellent restaurants retain customers better.

Thus, excellent service is essential in today’s restaurant market, but excellent service requires an investment level that most independent restaurants can’t afford due to employee turnover. In practice, most independent restaurants operate on razor-thin margins.

Earlier, we mentioned that average restaurant margins have dropped from 20% to 4%. That’s thin. But these top-line numbers often lack vitality, so I read detailed breakdowns from restaurant owners to better understand the reality.

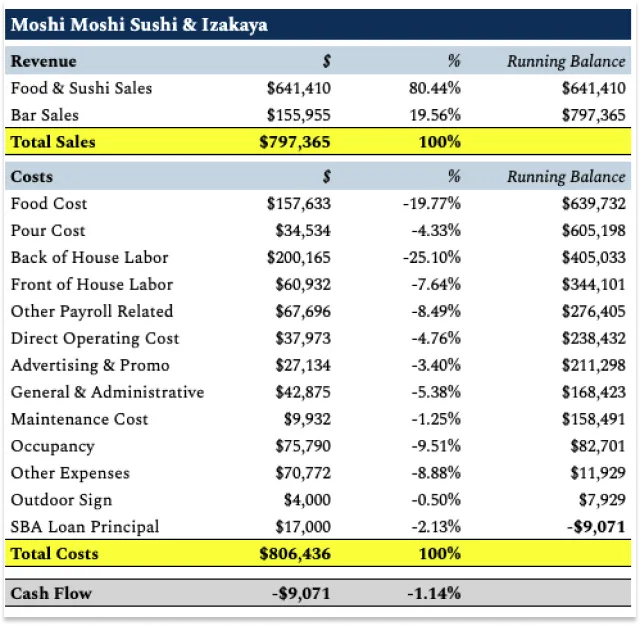

In The Financial Reality of Restaurant Ownership, Charlie Anthe, co-owner of Seattle’s Moshi Moshi Sushi & Izakaya, breaks down his restaurant’s economics line by line.

In 2019, Moshi Moshi’s total food and beverage revenue was $797,365.

It paid $192,168 for food and beverage costs (-24.1%), $200,165 for back-of-house labor (-25.10%), $60,932 for front-of-house labor (-7.64%), and other labor-related expenses, totaling $328,793 in labor costs (-41.23%). Gross profit after these “prime costs” was $276,404 (34.66%).

Next come fixed and semi-variable costs. Direct operating expenses (aprons, uniforms, pest control, kitchen supplies, paper goods) were $37,973 (-4.76%), advertising and promotion (including third-party delivery fees) was $27,134 (-3.40%), general and administrative (credit card processing, legal, accounting) was $42,875 (-5.38%), maintenance was $9,932 (-1.25%), and occupancy (mostly rent) was $75,790 (-9.51%).

If you’re tracking, Moshi Moshi Sushi & Izakaya’s operating net income was $82,697 (10.37%). Not bad! Well above average.

Then come other expenses—interest and owner salary—totaling $70,772 (-8.88%), leaving net profit at just $11,928 (1.50%). Still profitable! That’s good!

Wait. We also need to include cash outflows not shown on the P&L. A new outdoor sign cost $4,000, and SBA loan principal payments were $17,000. As Charlie says, “Just like that, our barely-profitable restaurant ended the year with $8,000 less cash than it started with.”

I put all this into a spreadsheet with a running balance column so you can feel the anxiety of a restaurant owner watching cash dwindle.

Charlie Anthe’s Data

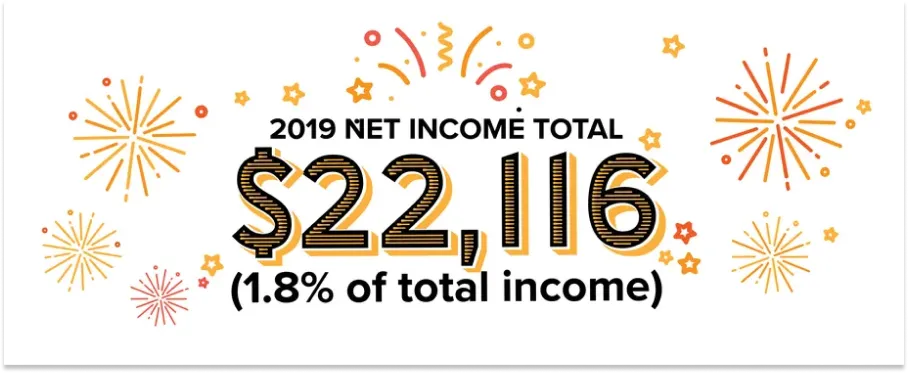

In Boston, far across the country, Irene Li is chef and owner of Mei Mei Dumplings. Mei is a serious chef: “In 2016, she won the Eater Young Gun award; she was a Zagat 30 Under 30 winner and a six-time James Beard Rising Star Chef semifinalist.” She shared her restaurant’s finances with Eater.

I won’t go into the gory details, but with $1,215,037 in revenue from the restaurant and catering, Mei Mei ended 2019…

Eater

“And that doesn’t include debt repayment and taxes,” Li says. “Nothing special. Not great either. But that’s where we are.”

Both examples are from 2019. Then COVID hit. Then food prices rose. Things got worse.

So what do you do? Reduce food costs or labor? Move to a cheaper neighborhood? How do you invest in training when every minute spent training is money spent not generating revenue? How do you invest in customer experience when you don’t know if customers will return?

One answer the industry has offered is consolidation. In Refactoring Restaurants, Byrne Hobart writes:

Chain restaurants account for 77% of total U.S. restaurant visits and are growing over time. In the independent sector, the back-end has consolidated, with food distribution consolidating via public companies and private equity, and on the front-end, more demand is funneled through review sites or fulfilled directly by delivery companies.

I don’t know, man. A world with cheap energy, flying cars, miracle cures, and increasingly homogenized dining options prepared and served by robots seems a bit dystopian.

We want the opposite. Thousands of vibrant independent restaurants, each offering something unique, each providing magical personalized experiences. We want to be locals at our favorite spots and know our favorite restaurants will stick around with us.

Blackbird wants to help make that happen.

How It Works

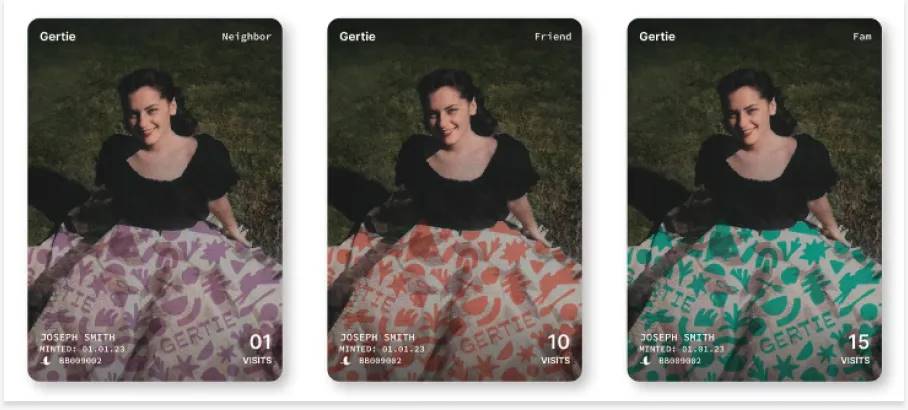

Blackbird launched in April 2023, starting with one restaurant and a simple premise: well-designed loyalty programs can create direct relationships between restaurants and customers, “the more you visit, the better your experience gets.”

Gertie’s membership card

Blackbird partners with restaurants to build custom loyalty programs or memberships. Customers sign up for a restaurant’s membership, receive a membership card as an NFT, use the card via the Blackbird app, and check in by tapping a Blackbird NFC chip when visiting. Restaurants reward customers in various ways to encourage repeat visits.

The first restaurant on the platform, Gertie, decided on a “Friends & Family” program, which Ben described in a blog post.

Customers become “Neighbors” on their first visit, “Friends” on their tenth, and “Family” on their fifteenth. The design, naming, and tiering are all configured by the restaurant. First check-in gets a free cookie from a nearby bakery. Second check-in gets free coffee. Over time, generic freebies give way to the kinds of perks you’d expect as a regular, like a personalized coffee cup waiting for you whenever you arrive.

A restaurant’s membership card doesn’t need to be an NFT. It could simply live in the app, as long as you trust the app will continue to run. Blackbird could simply share customer data with the restaurant, stored in a database or spreadsheet in case the app stops working. But from the beginning, the plan wasn’t limited to one restaurant or just membership programs.

Soon, Blackbird added more restaurants in NYC and new tools to connect with, understand, and incentivize customers. In May, it announced its native token $FLY via a whitepaper and blog post.

While memberships are restaurant-specific, $FLY will be a “cross-industry loyalty currency.” For example, each time you check in at Gertie, you might earn 1,000 or 5,000 $FLY. Restaurants might offer higher $FLY rewards to encourage visits during specific hours. So every time you check in at a specific restaurant on the Blackbird network, that restaurant knows you’re becoming more of a regular, and other restaurants know you’re a valuable customer.

In the $FLY announcement blog, Ben spoke with Marguerite Mariscal, CEO of Momofuku and Blackbird Labs board member, about what $FLY could unlock:

“I think what Blackbird potentially offers is a broader network bringing together people who love going out to eat and love hospitality, but who may not have visited our restaurants yet. So it’s not just identifying relatively frequent diners and the ability to make them regulars, but also these frequent diners who are first-time guests. If a restaurant knows a new guest dines out seven nights a week—because they see a huge $FLY balance and crazy dining history—but has never been to that restaurant, he should be treated as well as someone who’s been dining at your restaurant forever because he’s a great customer.”

This is what I mean by “scaling the regular experience.” Walk into any restaurant on the network and be treated like a regular.

For restaurants, Mariscal notes, the flow of customer information—“still water or sparkling? Left-handed? What was the last bottle of wine?”—is still a manual process, meaning it’s inherently hard to scale. In the same vein, a16z crypto’s Jay Drain told me Blackbird will “handle all those notes employees scribble on paper or in spreadsheets when they go to Don Angie, or leave in Resy when they have time.” Mariscal says that with better tools, “we’re increasing the number of regulars because of enhanced service and attention.”

The key insight here is that the “regular” experience is a form of capital—more accurately, social capital. It’s valuable to restaurants (they benefit from repeat business and word-of-mouth marketing) and to customers (they enjoy better service and status). Yet this capital has traditionally been illiquid and non-transferable. You can’t sell your regular status at one restaurant to become a regular at another. With $FLY, you can.

Beyond memberships and $FLY, Blackbird continues experimenting with new ways to help restaurants acquire customers and enhance customer experiences.

“Blackbird is a young company,” Ben explains. “We naturally like to experiment and iterate a lot to find solutions.”

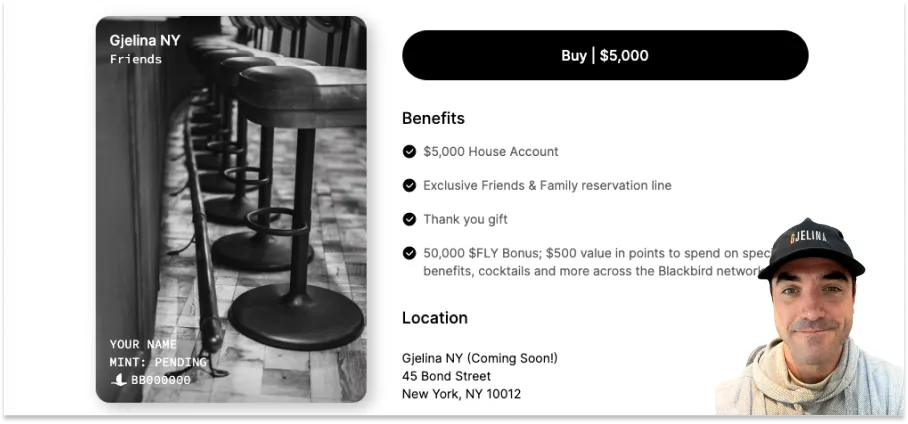

For example, in February, it launched Gjelina House Accounts.

The Gjelina Group, home to LA hotspots Gjelina and Gjusta, opened a NYC restaurant that closed after just 30 days due to a fire. When Ben had dinner with Gjelina Group CEO Shelley Armistead, she mentioned they were missing funds to reopen. Ben suggested a partnership: Gjelina could sell House Accounts on Blackbird to raise funds, and Gjelina would treat supporters as regulars with coveted House Accounts.

I thought it was brilliant and joined on day one. Prepay $5,000, get a $5,000 House Account to spend when the restaurant reopens, a hotline to reserve hard-to-get tables, a gift (they sent a Gjelina hat and delicious granola), and 50,000 $FLY. Smart deal: I’ll have a go-to spot, and enough $FLY that other restaurants on the network might treat me like a regular too. Win-win.

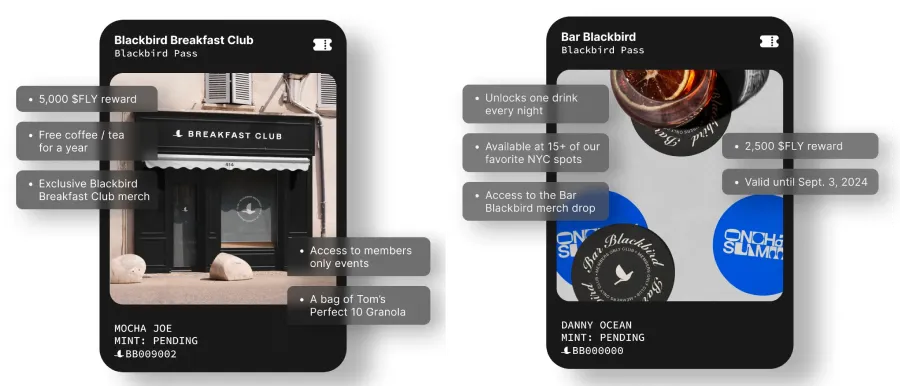

In March, Blackbird launched Breakfast Club, offering a different but equally compelling deal: pay $85 to get free coffee or tea for a year at 14 city cafes, plus merch, event access, and 5,000 $FLY. Plus, since you’re likely to pick one of these cafes in your neighborhood, restaurants get repeat customers, and you keep running into others who joined Breakfast Club. Win-win.

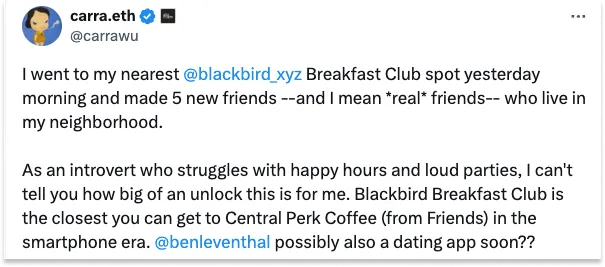

a16z crypto partner Carra Wu tweeted that she met new friends at her local Fairfax:

carra.eth: Yesterday morning I went to the nearest @blackbird_xyz breakfast club to my house and met 5 new friends--I mean real friends--who all live near me. As an introvert who struggles with happy hours and loud parties I can't tell you how much of an unlock this is for me. The blackbird breakfast club is as close as it gets to central perk coffee from Friends in the smartphone era. @benleventhal might launch a dating app soon?

In June, Blackbird launched its latest club: Bar Blackbird. Similar deal: $50 gets you a free drink every night at 15+ NYC bars (when buying a second drink) and 2,500 $FLY.

Breakfast Club and Bar Blackbird

Members enjoy free drinks and the “buy-back” experience every time they walk into their favorite bar. Restaurants gain new customers who turn into regulars. Win-win.

More win-win experiments will follow. Earlier this month, Blackbird partnered with Miami’s Cowy Burgers for a three-day pop-up at Standard Biergarten, open only to Blackbird users who claimed (free) Blackbird x Cowy Burger Access Passes. A burger club might be coming.

But Blackbird’s biggest new release is clearly not an experiment. It’s core to their business and their mission to help restaurants become more profitable.

Today, Blackbird officially launches Blackbird Pay, following several months of feature rollouts.

“Blackbird initially focused on loyalty, which is optional,” Fred explained in our conversation last week, “but when combined with payments, it becomes essential.”

Here’s how it works.

When you check in at a Blackbird restaurant, a tab opens. You can split the bill with friends, pay with a debit or credit card in the app, or even pay with $FLY. From the customer’s perspective, this converts your social capital into real capital usable for dining.

There’s one more thing…

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News