Narrative Tug-of-War: Don't Focus on Extreme Arguments, Focus on the Narrative Itself

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

Narrative Tug-of-War: Don't Focus on Extreme Arguments, Focus on the Narrative Itself

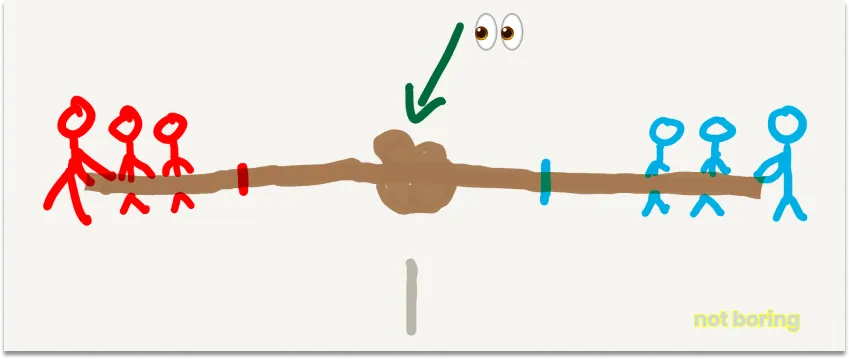

Don't focus on the people at both ends of the tug-of-war; focus on the knot in the middle.

Written by: Packy

Translated by: TechFlow

One of the biggest shifts in how I view the world over the past year has been seeing ideological debates as a game of narrative tug-of-war.

For every narrative, there exists an equal and opposite one—and it’s almost inevitable.

One side pulls hard toward an extreme, while the other pulls back toward its own position.

For example: AI will destroy us all ←→ AI will save the world.

It starts as a small disagreement, then escalates into completely opposing worldviews. A subtle conversation becomes a slogan. People who were once your opponents become your enemies.

If you focus on the extremes—the teams pulling on either end of the rope—it's easy to get worked up. And certainly easy to nitpick everything they say and point out everything they ignore or leave out.

But here's my suggestion: don’t do that. Focus instead on the knot in the middle.

As each side tries to pull it further toward themselves, this knot moves back and forth—and it is the most important thing to watch.

For them, it's a battle of ideas. For us, it's where new things emerge.

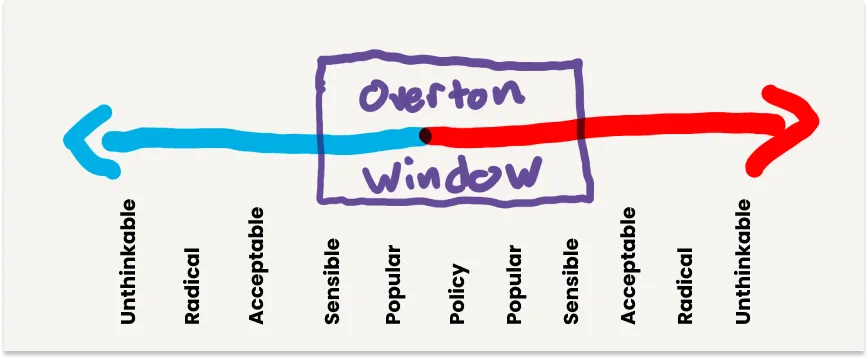

There’s a concept called the Overton Window: the range of policies considered politically acceptable to the majority at any given time.

Since Joseph Overton introduced the idea in the mid-1990s, the concept has expanded beyond government policy. Today, it describes how ideas enter mainstream discourse and shape public opinion, social norms, and institutional practices.

The Overton Window is the knot in the narrative tug-of-war. The teams pulling on either end don’t actually expect everyone to agree with and adopt their views; they just need to pull hard enough to shift the window in their direction.

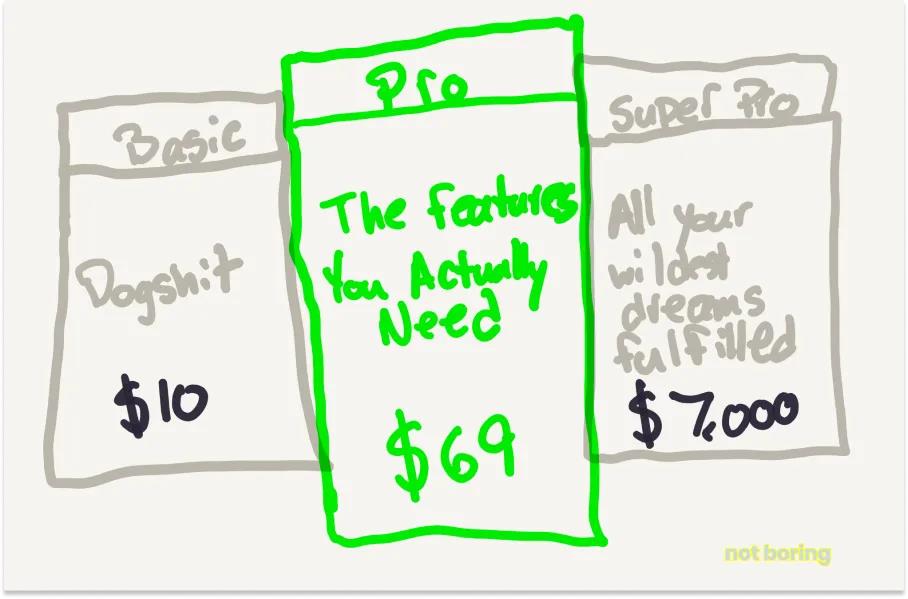

Another way to think about it is price anchoring—when a company offers multiple pricing tiers, knowing you’ll likely pick the middle one.

No one expects you to pay $7,000 for the ultra-pro version. They just know that by showing it, you’ll be more willing to pay $69 for the pro version.

Narratives work similarly—but instead of a single company strategically setting prices to maximize your chance of buying the pro version, it’s independent and opposing teams trying to figure out how to pull the knot hard enough to bring it back to what they consider an acceptable position. When you think about it, it’s cultural magic.

I can illustrate this idea with many examples, but let’s focus on tech—specifically, degrowth vs. growth, or EA vs. e/acc.

EA vs. e/acc

One of the biggest debates in my world (spilled into global awareness during OpenAI’s recent drama) is effective altruism (EA) versus effective accelerationism (e/acc).

It’s the latest manifestation of the long-standing struggle between those who believe we should keep growing and those who don’t—and a perfect case study of how this narrative tug-of-war plays out.

When viewed in isolation, both sides appear extreme.

EA (which I’ll use as shorthand for the AI risk camp) believes AI is very likely to kill us all. Given that trillions of humans could exist over the next few thousand years, even a 1% chance of AI wiping us out means preventing it could save tens or hundreds of billions of lives. We must halt AI development before reaching AGI, no matter the cost.

Eliezer Yudkowsky, a leader in this camp, wrote in Time:

Shut down all large GPU clusters. End all large-scale training. Set a cap on the amount of compute anyone is allowed to use when training AI systems, and gradually lower it over the coming years to compensate for more efficient training algorithms. No exceptions for governments or militaries. Immediately reach multinational agreements to prevent banned activities from moving elsewhere. Track all GPU sales. If data centers are found, bomb them from the air.

The idea of bombing data centers to stop AI development is genuinely absurd.

e/acc (my shorthand for the pro-AI camp) believes AI won’t kill us all, and we should accelerate it by any means necessary. They see technology as good, capitalism as good, and their combination—the technological capital machine—as “an engine of perpetual material creation, growth, and abundance.” We must protect the technological capital machine at all costs.

Marc Andreessen brands himself “e/acc” in his Twitter bio and recently published The Techno-Optimist Manifesto, making the case for technological progress. Certain passages particularly enraged AI skeptics:

We have enemies.

They are not bad people, but they have bad ideas.

For the past sixty years, our society has been under attack by a broad-based movement to destroy technology and life itself, under various banners such as “existential risk,” “sustainability,” “ESG,” “Sustainable Development Goals,” “social responsibility,” “stakeholder capitalism,” “precautionary principle,” “trust and safety,” “tech ethics,” “risk management,” “degrowth,” “limits to growth.”

This destruction movement is based on bad old ideas—many zombie ideas derived from communism, which have been and continue to be disastrous.

As many journalists and bloggers quickly pointed out, things most people consider good—like sustainability, ethics, and risk management—sound ridiculous in this framing.

What critics of both pieces miss is that neither argument should be taken literally. Nuance isn't the point of any individual argument. You pull hard at the edges so nuance can emerge in the center.

While both sides have extremists—one demanding AI be shut down entirely, the other calling for uncontrolled growth of technological capital without oversight from any entity, government or corporate—what’s really happening is a narrative tug-of-war.

EA wants to see AI regulated and aims to be the ones writing those regulations. e/acc wants AI to remain open and free from control by any single entity, whether government or corporation.

One side draws attention by warning that AI will kill us all, scaring the public and governments into swift regulation. The other side counters by arguing AI will save the world, preventing premature rules so people can experience its benefits firsthand.

Personally, unsurprisingly, I stand with the techno-optimists. But that doesn’t mean I think technology is a panacea or that there aren’t real problems to solve.

It means I believe progress is better than stagnation, that problems have solutions, that history shows technological advancement and capitalism have improved human living standards, and that bad regulation poses a greater risk than no regulation.

While the world changes through narrative tug-of-war, there is also truth. Pessimists—from Malthus to Ehrlich—have been proven wrong, yet fear spreads, so the mainstream narrative remains biased against technology. What’s truly concerning is that restrictive regulation may lock in before the truth emerges.

Because the problem with this narrative tug-of-war is that it’s not a fair game.

The anti-growth side only needs to pull hard enough for long enough to get regulations enacted. Once in place, they’re hard to overturn—and often ratchet tighter over time. Global nuclear energy adoption is a clear example.

If they can pull the knot past the regulatory line, they win—and the game ends.

The pro-growth side must keep pulling hard enough for long enough for the truth to surface amid the chaos of new technology, for entrepreneurs to build products that prove the promise, and for creative minds to devise solutions that address problems without stifling progress.

They need to keep the tug-of-war going long enough for solutions to emerge in the middle.

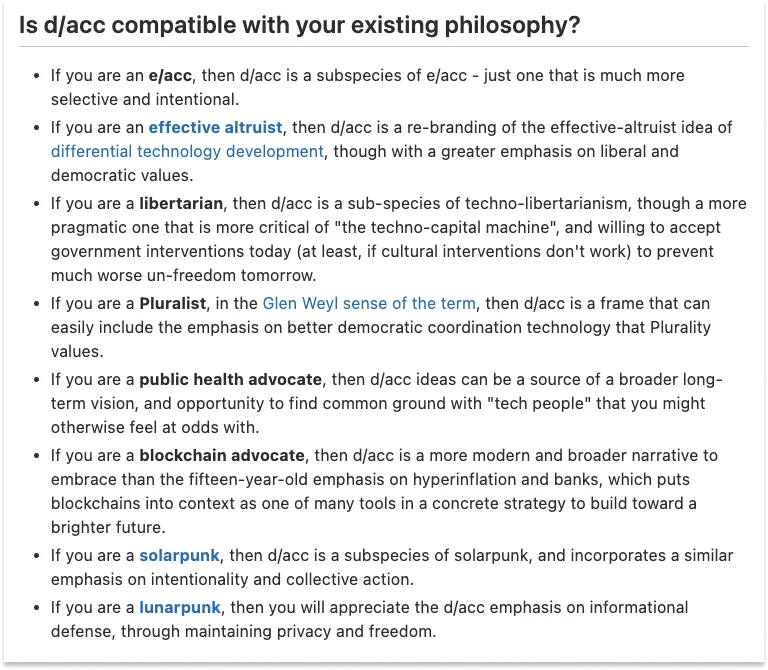

Vitalik Buterin, co-founder of Ethereum, wrote an essay titled My techno-optimism, proposing a third way: d/acc.

He writes that “d” can stand for many things—particularly defense, decentralization, democracy, and differentiation. It means developing AI using technology in ways that guard against potential problems and prioritize human flourishing.

On one side, the AI safety movement campaigns with the message: “You should stop.”

On the other, e/acc says: “You’re already a hero as you are.” Let’s move forward.

Vitalik proposes d/acc as a third, middle path:

A d/acc message would be: “You should build, and build things that benefit you and human flourishing—but do so more selectively and consciously, ensuring what you build helps you and humanity thrive.”

He sees this as a synthesis that can appeal to people across philosophies—as long as their belief isn’t “regulate technology into oblivion.”

Without EA and e/acc applying pressure at both extremes, there might be no space for Vitalik’s d/acc in the middle. The extremes themselves lack nuance, creating space for nuance to emerge in the center.

If EA wins, regulations will block development or concentrate it in a few companies—and that middle space disappears. If the goal is regulation, then non-regulatory solutions don’t exist.

But if the goal is human flourishing, there’s room for many solutions.

Although Vitalik clearly disagrees with parts of e/acc, both Marc Andreessen and Beff Jezos—an anonymous co-founder of e/acc—shared Vitalik’s post. This suggests they care about better solutions, not just their own.

Whether d/acc is the answer or not, it perfectly captures the point of the extremes. Only when e/acc sets the outer boundary does a solution involving merging humans and AI via Neuralink seem like a reasonable, moderate step.

In this and other narrative tug-of-wars, extremes play a role—but they aren’t the end goal. For every EA, there is an equal and opposite e/acc. As long as the game continues, solutions can emerge from this tension.

Again: don’t focus on the people pulling at the ends. Focus on the knot in the middle.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News