Public Chain Shardeum: Another Possibility for Sharding

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

Public Chain Shardeum: Another Possibility for Sharding

A truly sharded and scalable blockchain needs to be built from scratch.

Author: Beam, Jsquare Research

On September 15, 2022, Ethereum completed "The Merge." This was a historic moment—the culmination of five years of preparation and six delays. Due to repeated debugging, prolonged development, and widespread public anticipation, many mistakenly believed that the Merge would naturally bring greater scalability, security, and sustainability. But in reality, it does not. To illustrate using the analogy of two trains, transitioning from PoW (Proof-of-Work) to PoS (Proof-of-Stake) is merely changing the track and wheels—it doesn’t directly lead to faster speeds, larger capacity, or lower ticket prices. The real solution capable of achieving these three goals is an integrated system: a sharded mainnet combined with Layer2 solutions that enhance scalability.

As Ethereum co-founder Vitalik Buterin has pointed out, sharding is a scaling solution to the scalability trilemma—by dividing network nodes into smaller groups that process different sets of transactions in parallel. By distributing the massive data processing burden across the entire network, it’s like adding more checkout lanes at Walmart—this intuitively reduces waiting time and improves checkout efficiency.

Figure 1: Simple logic of sharding

This is the basic logic of sharding—direct and simple. Yet, as they say, the devil lies in the details. While the principle and direction are correct, implementation inevitably brings many challenges. This article aims to clarify the direction and dilemmas on the path of “sharding,” mapping out a vision that balances ambition with practicality. By comparing existing sharding solutions, we identify common issues and propose a feasible new direction: Shardeum and dynamic sharding.

I. Understanding "Sharding"

Simply put, considering the constraints of the impossibility triangle and taking Ethereum as the origin point (0,0), we can classify current blockchain scalability approaches into two broad categories based on “vertical” and “horizontal” thinking:

Vertical Scaling: Achieved by improving the performance of existing system hardware. This involves building a decentralized network where each node possesses supercomputing power—requiring every node to have “better” hardware. This approach is straightforward and effective for initial throughput improvements, especially suitable for high-frequency trading, gaming, and other latency-sensitive applications. However, this method limits network decentralization, as the cost of running validator or full nodes increases. Maintaining decentralization is constrained by the general pace of computing hardware advancement (what’s known as “Moore’s Law”: transistor count on chips doubles every two years while computing costs halve).

Horizontal Scaling: There are several approaches to horizontal scaling. One involves distributing transaction workloads across multiple independent blockchains within an ecosystem. Each chain has its own block producers and execution capabilities, allowing for deep customization of each chain’s execution layer—such as node hardware requirements, privacy features, gas fees, virtual machines, and permission settings. Another approach is modular blockchains, which divide the blockchain architecture into execution, data availability (DA), and consensus layers. The most popular modular mechanism today is rollups. A third method splits a single blockchain into many shards for parallel execution. Each shard functions like an independent blockchain, enabling numerous blockchains to operate simultaneously. Typically, there’s also a main chain whose sole purpose is to keep all shards synchronized.

It should be noted that these scalability strategies do not exist in isolation. Each solution represents a trade-off within the impossibility triangle, supported by incentive mechanisms shaped by economic forces in the system to achieve macro and micro-level balance.

To discuss “sharding,” let’s start from the beginning.

Let’s consider a scenario: checking out at Walmart. To improve checkout efficiency and reduce customer wait times, we expand from a single checkout lane to ten checkout counters. To prevent accounting errors, we need unified rules:

-

First, if we have 10 cashiers, how should we assign them to specific counters?

-

Second, if 1,000 customers are queuing, how should we decide which counter each customer goes to?

-

Third, how should the ten separate ledgers corresponding to the ten counters be consolidated?

-

Fourth, to prevent mismatches, how can we prevent cashier errors?

These questions correspond directly to key issues in sharding:

-

How should network nodes/validators be assigned to specific shards? That is: How to perform Network Sharding;

-

How should each transaction be assigned to a shard? That is: How to perform Transaction Sharding;

-

How should blockchain data be stored across different shards? That is: How to perform State Sharding;

Complexity implies risk. On top of all this, how can we avoid fragmentation of the system's overall security?

01 Network Sharding

If we simply view a blockchain as a decentralized ledger, whether under PoS or PoW consensus, the goal is to allow nodes to compete for bookkeeping rights according to established rules, ensuring ledger correctness. Network sharding refers to another set of rules that divide the blockchain network into shards, enabling each shard to process on-chain transactions and compete for bookkeeping rights with minimal inter-shard communication—essentially, the grouping rule for nodes.

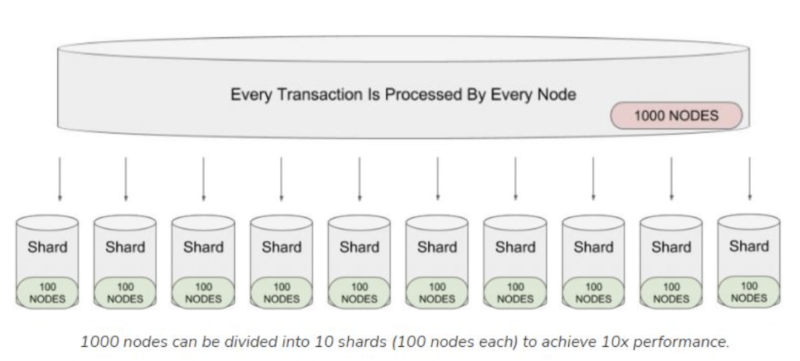

The challenge here is that as internal nodes are divided into different shards, the difficulty and cost for attackers drop sharply. We can reason: if the grouping process and outcome are fixed and predictable, an attacker aiming to control the entire blockchain only needs to target and compromise a single shard by bribing some of its nodes.

Alexander Skidanov, founder of Near, describes this issue: If a single chain with X validators decides to hard fork into a sharded chain and divides the X validators into 10 shards, each shard now has only X/10 validators. Compromising one shard then requires corrupting just 5.1% (51%/10) of total validators. This leads to the second question: Who selects validators for each shard? Controlling 5.1% of validators is only harmful if all those validators end up in the same shard. If validators cannot choose their shard, participants controlling 5.1% of validators are extremely unlikely to place all of them in the same shard, greatly reducing their ability to disrupt the system.

Figure 2: Attack difficulty on a single shard is significantly reduced

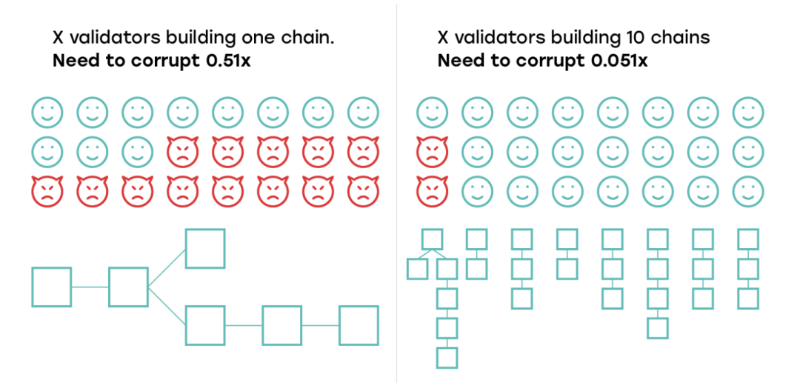

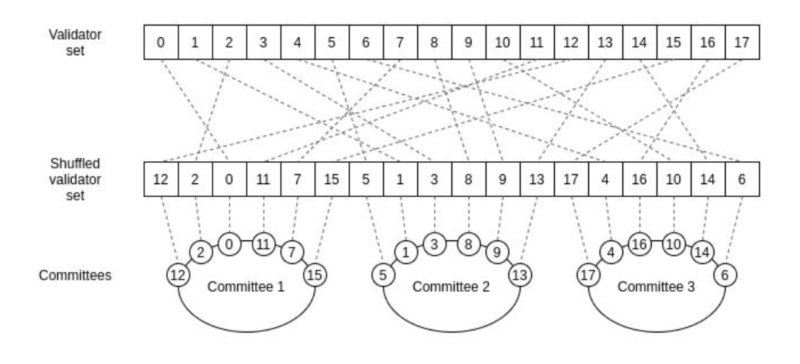

A sharding system must develop a mechanism to trust that transactions won't be reversed from external shards. So far, the best answer may be ensuring the number of validators per shard exceeds a minimum threshold, making it highly improbable for malicious actors to overwhelm a single shard. The most common method is introducing a degree of unbiased randomness—using mathematical methods to minimize the attacker’s success probability. For example, Ethereum randomly selects validators for each shard from the entire validator pool and rotates them every 6.4 minutes (the length of an epoch).

Figure 3: Proposed validator rotation in Ethereum 2.0

Put simply: randomly group nodes, then assign work to each group for independent validation.

However, randomness in blockchains is a highly challenging topic. Logically, the random number generation process should not depend on computation from any specific shard. Many existing designs address this by creating a separate blockchain to maintain the entire network. In Ethereum and Near, this is called the Beacon Chain; in Polkadot, the Relay Chain; in Cosmos, the Cosmos Hub.

02 Transaction Sharding

Transaction sharding refers to the rules determining “which transactions go to which shards,” enabling parallel processing while avoiding double-spending. The choice of blockchain ledger model affects how transaction sharding is implemented.

Currently, there are two types of accounting models in blockchain networks: UTXO (Unspent Transaction Outputs) and Account/Balance models. BTC exemplifies the former; ETH, the latter.

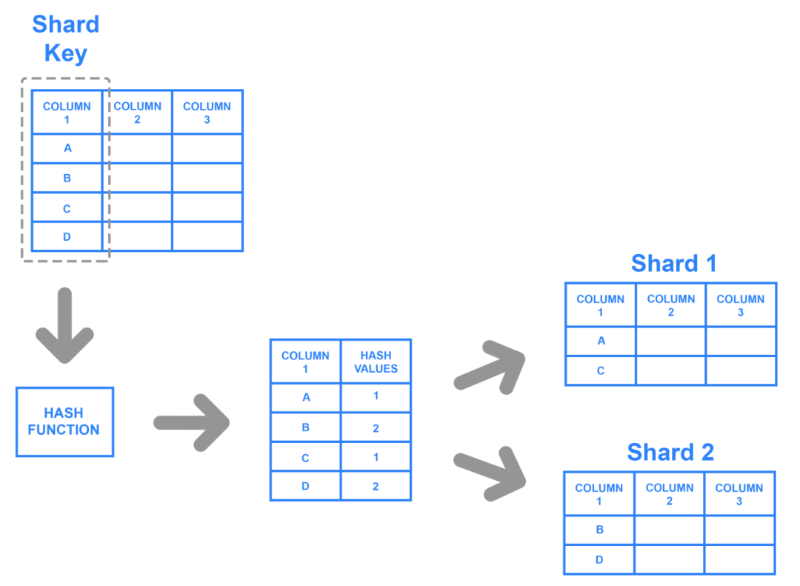

UTXO Model: In BTC transactions, each transaction has one or more outputs. A UTXO is an unspent output from a blockchain transaction, usable as input for a new transaction. Spent outputs cannot be reused—similar to cash payments and change: a customer pays with one or more bills, and the merchant gives back change in one or more bills. Under the UTXO model, transaction sharding requires cross-shard communication. A transaction may include multiple inputs and outputs, with no concept of accounts or balance records. One possible method: use a hash function on a transaction input value to generate a discrete hash value determining which shard the data belongs to. See below:

Figure 4: A possible transaction sharding approach for UTXO

To ensure consistent placement in the correct shard, the value fed into the hash function should come from the same column. This column is called the Shard Key. Transactions producing a hash value of 1 go to Shard 1, those producing 2 go to Shard 2, etc. The drawback: shards must communicate to prevent double-spend attacks. Restricting cross-shard transactions limits platform usability, while allowing them requires balancing communication costs against performance gains.

Account/Balance Model: The system records each account’s balance. During a transaction, it checks if the account has sufficient funds—like bank transfers, where banks record account balances and only approve transactions if the balance exceeds the transfer amount. Under this model, since a transaction has only one input, sharding by sender address ensures multiple transactions from the same account are processed in the same shard, effectively preventing double-spending. Thus, most blockchains adopting sharding, like Ethereum, use the account-based ledger model.

03 State Sharding

State sharding refers to how blockchain data is distributed and stored across different shards.

Using our Walmart queue example again: each counter has its own ledger. How are these ledgers maintained? If a customer uses counter A today, but goes to counter B tomorrow, and counter B lacks the customer’s past account information (e.g., for gift card payments), what happens? Does counter B query counter A for the customer’s info?

State sharding is the biggest challenge in sharding—more difficult than network and transaction sharding. Because under sharding, transactions are processed in different shards based on address, meaning state is stored only in the shard corresponding to that address. This raises the issue of cross-sharding interactions.

Consider a transfer: Account A sends 10U to Account B. Suppose A’s address is assigned to Shard 1—transaction records are stored in Shard 1. B’s address is in Shard 2—records stored in Shard 2.

When A sends to B, a cross-shard transaction occurs. Shard 2 must query Shard 1 for past transaction records to verify validity. If A frequently sends to B, Shard 2 must constantly interact with Shard 1, lowering processing efficiency. However, without downloading and verifying an entire shard’s history, participants cannot be certain that the interactive state results from a valid sequence of blocks that form the canonical chain in that shard.

Therefore, compared to non-sharded single chains, sharded systems face a new challenge: users cannot directly and fully verify the validity and availability of any given chain due to data volume. Users must be provided with maximally trustless yet practical indirect methods to verify which chain is fully available and valid, so they can determine the canonical chain. In practice, developers can use techniques such as committees, SNARKs/STARKs, fisherman mechanisms, and fraud and data availability proofs.

Two approaches can solve this. One is synchronous cross-sharding (Synchronous), i.e., Tight Coupling: whenever a cross-shard transaction is executed, the relevant blocks containing state transitions occur simultaneously, with nodes across shards collaborating. This feels natural and offers the best user experience. The most famous design is Merge Blocks, but implementing it is complex. It requires validators across shards to synchronize communication. If demand for cross-shard transactions is high, performance may degrade as more shard workers must collaborate.

The other approach is asynchronous cross-sharding (Asynchronous), i.e., Loose Coupling. This is more widely adopted—for example, by NEAR, Ethereum, Cosmos, Kadena. The biggest challenge here is transaction atomicity. According to Jordan Clifford, co-founder of Scalar Capital: imagine the concept of a receipt. The recipient proves they received tokens from another shard by providing the Merkle path of the transaction in the source shard. The destination shard uses this receipt to credit the recipient’s account. This must happen atomically. Either both sender and recipient accounts are updated together, or neither. Any gap or partial failure could allow the sender to trick the recipient into believing they received funds they never will.

Here’s a real-life analogy for atomicity: suppose you want to take a beach trip and need to book both a flight and a hotel. If you can’t book the hotel, you don’t want to buy the plane ticket; if you can’t book the flight, you don’t want to reserve the hotel. That’s atomicity—either everything succeeds, or nothing does.

II. Exploration and Attempts in Sharding

Recalling our earlier discussion on sharding, we highlighted key issues:

First, how to implement state sharding—how blockchain data is distributed across shards—and how to balance efficiency during cross-shard communication.

Second, how to handle transaction atomicity—ensuring one shard’s modification to shared state is promptly known by others, otherwise state inconsistencies arise.

Below, we review well-known public chains and their technical solutions, revealing partial patterns and discussing Shardeum’s innovativeness and advancement.

01 Computation Sharding

Zilliqa was one of the earliest smart contract platforms to attempt sharding—a beneficial and effective exploration of sharding technology.

Founded in 2017 by a team of researchers and scholars affiliated with the National University of Singapore, Zilliqa’s primary goal was solving scalability, specifically built for compute-intensive tasks. The Zilliqa network achieves high transaction throughput via a parallelization process called computation sharding, distributing transaction processing tasks across various shards in the network.

In terms of the sharding process, Zilliqa divides it into two parts: first, selecting Directory Service (DS) committee nodes, then initiating the sharding process and assigning nodes to each shard. Once transactions are validated within a shard, they are verified across the entire network and enter a global state—a single verifiable source of truth combining all shard transactions onto the Zilliqa blockchain.

Simply put, considering the three main functions of blockchain nodes:

-

- Processing transactions

-

- Packaging transactions and broadcasting to other nodes

-

- Storing the entire network’s historical ledger

Zilliqa adopts a concise and effective approach to address cross-shard communication and atomicity: it performs only computation sharding, not network or storage sharding. All nodes in the platform store the complete state, and every transaction is received by every node. To validate transactions, the network is partitioned based on account address space—called computation sharding, as it divides the computationally intensive work of transaction validation. However, since every node still receives every transaction and updates all account states, network bandwidth and storage operations remain bottlenecks—network and storage are not sharded, thus true scalability isn’t achieved.

02 Static State Sharding

A more common sharding method divides the account address space into multiple fixed-size regions called shards and assigns network nodes to different shards. This is called state sharding. Platforms like Near, Elrond, and Harmony adopt this approach. Although Ethereum initially planned to implement state sharding, its newer approach only shards data to improve accessibility.

2.1 Ethereum’s Data Sharding Vision

In Ethereum’s context, sharding will alleviate the burden of aggregating large amounts of data across the entire network, working in tandem with Layer2. This will continue to reduce network congestion and increase transactions per second.

It should be noted that as more efficient scaling paths emerge, Ethereum’s sharding plans continue to evolve. One version of Ethereum’s future sharding envisions data-availability-based sharding. “Danksharding” is a new sharding method that abandons the concept of sharded “chains” and instead uses sharded “blobs” to split data, while employing “data availability sampling” to confirm all data is available.

Another version builds on the first by adding extra functionality to each shard, making each shard more like today’s Ethereum mainnet—allowing shards to store and execute code and process transactions. Since each shard would contain unique smart contracts and account balances, cross-shard communication would enable transactions between shards. However, this version is still under community debate, as the combination of data availability (from version one) plus Layer2 already provides sufficient scalability for Ethereum, so the community is still evaluating version two’s economic cost versus benefit.

2.2 Harmony

Harmony is a PoS-based sharded network adopting a more standard sharding method—having multiple small blockchains called shards, each responsible for part of the state, and a coordinating blockchain called the Beacon Chain in Harmony. Following our previous discussion, let’s examine how Harmony addresses network sharding, transaction sharding, and state sharding from bottom to top.

Network Sharding: Harmony divides the validator network into different shards, each containing a distinct set of validators tightly connected and running consensus among themselves.

Transaction Sharding: In Harmony, transactions are handled by individual shards. This allows simultaneous transaction processing, increasing the blockchain’s total transaction capacity. For a transaction, users simply specify the shard_id field in the signed transaction to indicate the target shard.

State Sharding: In Harmony, validators in each shard store 1/N of the global state, maintaining their own blockchain and state database (N = number of shards). This alleviates validators’ concerns about data availability. Cross-shard mechanisms further improve state consistency across shards.

The Harmony mainnet supports thousands of nodes across multiple shards, generating blocks with instant finality in seconds. Its staking mechanism reduces centralization while supporting delegation, reward compounding, and slashing for double-signing. It employs EPoS (Effective Proof-of-Stake) and secure random sharding—protocol rules break large stakes into small portions and randomly distribute them across multiple shards, preventing anyone from concentrating their stake in a single shard and attacking it.

Regarding cross-shard transactions and beacon chain synchronization, validators from different shards send messages across shards via a globally connected network. According to Harmony’s official documentation, it uses "Kademlia cross-shard routing technology" to control network overhead from cross-shard communication, and employs "erasure coding" to optimize block broadcasting, reducing network pressure on broadcasters and avoiding sender-side bottlenecks—enabling efficient horizontal sharding expansion. Harmony has become the first sharded blockchain to complete cross-shard messaging. With an effective cross-shard messaging protocol and fully meshed design, seamless communication between shards will be possible. As the team actively works toward this goal, builders and developers can expect cross-shard messaging on Harmony later this year.

For builders and developers on Harmony, this is a major breakthrough—they’ll be able to build by integrating features and using data residing on different shards. Additionally, consistency of inter-shard data is crucial. These two pursuits will determine the sustainability of infinite scalability.

2.3 Elrond

Elrond is a high-throughput public blockchain designed for security, efficiency, scalability, and interoperability. Two features that distinguish Elrond are adaptive state sharding and a secure proof-of-stake consensus mechanism.

For transactions, data, and network, Elrond implements adaptive state sharding at all levels. Its dynamic adaptive sharding mechanism performs shard merging and splitting, considering the number of available validator nodes and network usage. Regular node reshuffling across shards maintains high resilience against malicious attacks. Each epoch, up to 1/3 of nodes in each shard are shuffled to other shards to prevent collusion. For randomness, it uses BLS signatures to protect the random source, ensuring it is unbiased and unpredictable.

Smart contracts on the sharded state architecture undergo cross-shard execution processes to balance load. The cross-shard load-balancing smart contract enables Elrond to run multiple smart contracts in parallel.

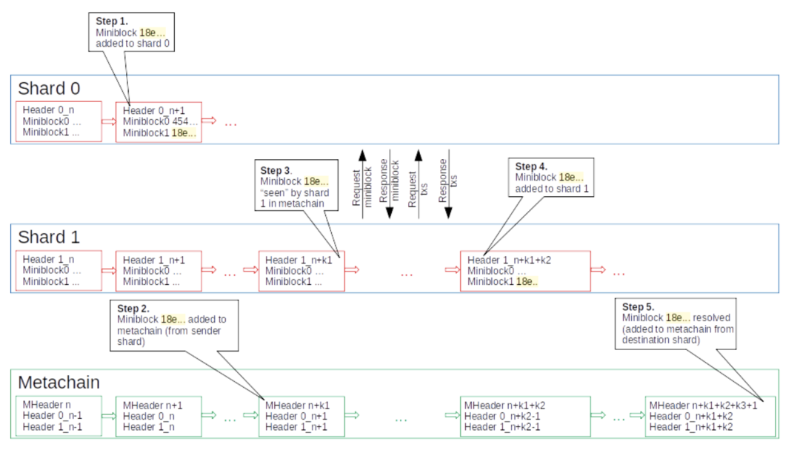

Additionally, for cross-sharding, Elrond adopts a design called the Meta Chain, enabling fast finality of cross-shard transactions within seconds. Based on its whitepaper, we simplify the process: assume the Elrond network has only two shards and the Meta Chain. Suppose a user generates a transaction from their wallet (address in Shard 0) sending EGLD to another user (address in Shard 1). The following steps process this cross-shard transaction.

Block structure consists of a block header (containing block info like nonce, round, proposer, validator timestamp, etc.) and a list of miniblocks per shard containing actual transactions. In our example, a block in Shard 0 typically contains 3 miniblocks:

-

Miniblock 0: Contains intra-shard transactions within Shard 0

-

Miniblock 1: Contains cross-shard transactions with sender in Shard 0 and receiver in Shard 1

-

Miniblock 2: Contains cross-shard transactions with sender in Shard 1 and receiver in Shard 0. These transactions were already processed in the sender’s shard (Shard 1) and will finalize after processing in the current shard.

There’s no limit to the number of miniblocks with the same sender and receiver in a block. Multiple miniblocks with identical sender/receiver pairs can appear in one block. In this process, the atomic unit for cross-shard execution is a miniblock: either all transactions in a miniblock are processed immediately, or none are—with retries in the next round.

Elrond’s cross-shard transaction strategy uses an asynchronous model. Validation and processing first occur in the sender’s shard, then in the receiver’s shard. Transactions are first dispatched in the sender’s shard because any transaction initiated from an account in that shard can be fully verified there. Then, in the receiver’s shard, nodes only need the execution proof provided by the Meta Chain, perform signature verification and replay attack checks, and finally update the receiver’s balance by adding the transaction amount.

Shard 0 processes intra-shard transactions in Miniblock 0 and a set of cross-shard transactions with receivers in Shard 1, grouped as Miniblock 1. The block header and miniblocks are sent to the Meta Chain. The Meta Chain certifies the block from Shard 0 by creating a new Meta Block containing the following info for each miniblock: sender shard ID, receiver shard ID, miniblock hash.

Shard 1 retrieves the hash of Miniblock 1 from the Meta Block, requests the miniblock from Shard 0, parses the transaction list, requests missing transactions (if any), executes the same Miniblock 1 in Shard 1, and sends the result block to the Meta Chain. After certification, the cross-shard transaction set is considered finalized. The figure below shows the number of rounds required to complete the transaction—from first inclusion in a miniblock to final certification of the last miniblock.

Figure 5: Elrond’s asynchronous cross-shard model

2.4 Near

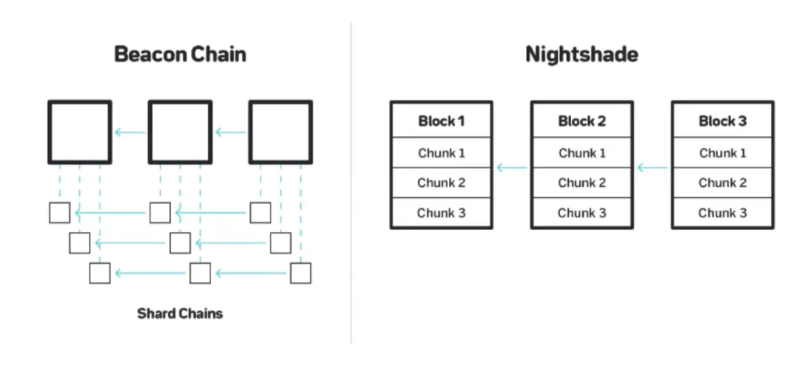

Near is a fully state-sharded, developer-friendly scalable public chain that proposes a new protocol and solution called Nightshade.

Unlike the two sharded public chains above, its architecture isn’t composed of a beacon chain and multiple shard chains. Instead, it models the system as a single blockchain, performing sharding at the block level, with many “chunks” in each shard.

Figure 6: Near abandoned the beacon chain approach, adopting Nightshade design

Nightshade models the system as a single blockchain where each block logically includes all transactions across all shards and changes the overall state of all shards. Physically, no participant downloads the full state or complete logical block. Instead, each network participant maintains only the state corresponding to the shard they validate, and the list of all transactions in a block is split into physical chunks—one per shard.

Under ideal conditions, each shard contains exactly one chunk per block—roughly corresponding to a sharded chain model where shard chains generate blocks at the same rate as the beacon chain. However, due to network latency, some chunks may be lost, so in practice each shard contains one or zero chunks per block.

In Nightshade, there are two roles: block producers and validators. At any time, the system contains w block producers and wv validators. In Near’s model, w=100, v=100, wv=10,000. The system has n shards—in Near’s model, n=1000. Nightshade has no shard chains; instead, all block producers and validators build a single blockchain—the main chain. The main chain’s state is divided into n shards. Each block producer and validator downloads only the subset of state corresponding to a subset of shards locally and processes/validates only transactions affecting those parts. Network maintenance occurs in epochs, each lasting several days.

Block producers rotate every block according to a fixed schedule. Block producers are ordered and repeatedly produce blocks in that order. For example, with 100 block producers, the first produces blocks 1, 101, 201, etc.; the second produces 2, 102, 202, etc. Since block production differs from validation and requires state maintenance, only sww/n block producers maintain state for each shard, and accordingly, only those sww/n block producers rotate to create chunks.

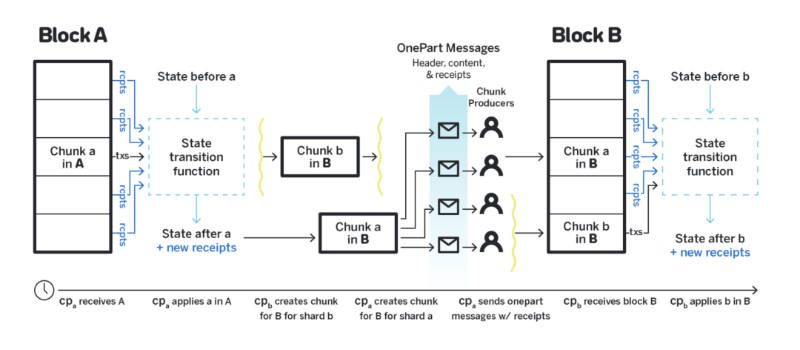

Regarding cross-sharding, if a transaction affects multiple shards in Near, it must be executed sequentially in each shard. The full transaction is sent to the first affected shard. Once included in that shard’s block and applied after being included in a chunk, it generates a receipt transaction routed to the next shard where the transaction must be executed. If more steps are needed, executing the receipt transaction generates new receipts, and so on. See the figure below:

Figure 7: Cross-shard transactions in Near

III. Shardeum and Dynamic State Sharding

From our analysis of Harmony, Elrond, and Near, we see answers to the two questions we raised:

1. Currently, the most common sharding method on Layer1 is dividing the account address space into multiple fixed-size regions called shards and assigning network nodes to different shards.

2. In state-sharded networks, transactions between contracts in the same shard are fast and simple, while cross-shard transactions are much slower—but not impossible. If a transaction affects multiple shards, it must be executed sequentially in each. Since transactions are grouped into blocks and consensus is block-level, a transaction might be confirmed in one shard but rolled back in another. Moreover, multi-shard transactions require additional processing time proportional to the number of affected shards.

Yet, through analyzing current market explorations and solutions, we’ve identified new issues in public chain sharding at this stage:

1. During cross-shard transactions, how can we guarantee atomic processing without requiring sequential execution across shards?

2. If the network adds nodes fewer than required for a full shard, how should the network handle these extra nodes?

As a professional investment firm focused on promoting large-scale blockchain adoption, reshaping web3 value paradigms, and empowering the future, Jsquare continuously monitors blockchain scalability and security. While closely watching Web3 application layers, we remain deeply confident in more decentralized infrastructure, seamless blockchain experiences, and a secure future powered by cryptography. Even though sharding isn’t a new concept, and despite years of exploration along this path, when we encountered Shardeum, we found their insights into the sharding landscape and revolutionary technical improvements worthy of our support. Shardeum offers two novel solutions addressing these very problems.

3.1 Shardeum and Transaction-Level Consensus

Shardeum has developed a unique technology and consensus algorithm combining Proof-of-Quorum (PoQ) with Proof-of-Stake (PoS). The consensus algorithm helps secure the network by collecting trustless votes and validating node stakes. Each transaction is processed in the order received, before being grouped into blocks/chunks.

Unlike the well-established public chains above, consensus on the Shardeum network occurs at the transaction level rather than the block level. This allows concurrent cross-shard transaction processing, unlike Near’s block-level consensus which requires sequential handling. This transaction-level consensus eliminates the complexity needed to ensure atomic processing. Thus, it achieves second-level finality and low latency, preventing network congestion.

3.2 Shardeum and Linear Scalability

To explain linear scalability, consider this scenario:

Near mainnet has one shard with 100 nodes, with plans to add more shards in the future. Harmony has 4 shards with 250 nodes each—1,000 nodes total. All contracts reside in one shard. Elrond has 3 shards and 1 Meta Chain, with 800 nodes per shard—3,200 nodes total.

If Harmony adds 100 more nodes—fewer than the 250 needed per shard—how should it handle these extra nodes? Could it split the 1,100 nodes into 11 shards of 100 nodes each?

That sounds better, but due to the static nature of shards, many additional nodes must join before creating a new shard. Adding just one node won’t improve overall performance. At minimum, you need enough nodes to meet the current “minimum shard size” (e.g., 100 nodes in Near)—because current sharding is static and does not support linear scaling. No production network has actually achieved splitting and merging of static shards.

Beyond “transaction-level consensus,” Shardeum’s whitepaper highlights a unique feature: dynamic state sharding. Unlike static sharding where all nodes cover the same address range, Shardeum’s virtual shards (i.e., dynamic shards) allow each node to hold different address ranges, with overlapping coverage—increasing complexity but enabling true linear scaling.

Through dynamic changes in the mapping between address space and nodes, plus a new data availability proof for cross-shard validation, Shardeum achieves near-perfect “linear scalability.” This transaction-level validation and confirmation may slightly sacrifice intra-shard performance but greatly benefits overall network scalability.

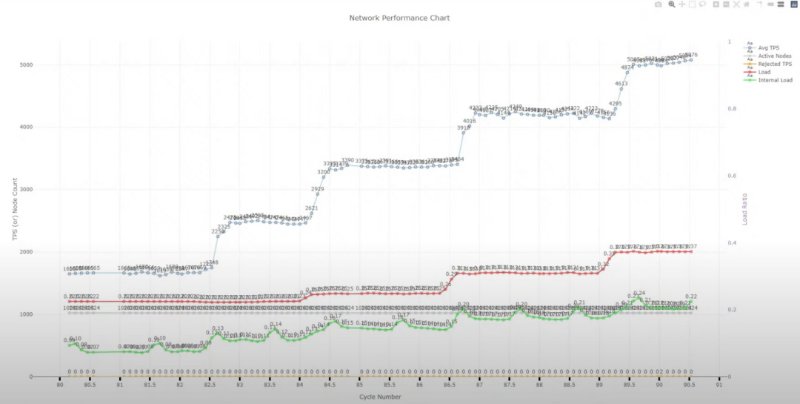

Currently, Shardeum has 10 shards with 128 nodes each—1,280 nodes total. Mainnet launch is expected in Q4 2022. Though still in development, the underlying Shardus technology has proven capable of linear scaling. In Q3 2021, a network of 1,000 nodes running on AWS t3.medium hardware demonstrated 5,000 TPS in cross-shard transactions.

Figure 8: In Q3 2021, Shardus demonstrated 5,000 TPS in cross-shard transactions

In August 2022, Shardeum successfully demonstrated 100 TPS on its Liberty 2.0 testnet with full sharding functionality via ERC20 token transfers.

Typically, a blockchain takes years to build and reach higher TPS, but Shardeum achieved this within four months of launching Liberty 1.0.

Currently, Shardeum tested and released Liberty 2.0 with 50 nodes, each storing approximately 1/5 of total data and processing 1/5 of total transactions.

IV. Conclusion

A truly sharded and scalable blockchain must be built from scratch.

Likewise, a community built on diamond-like consensus must be constructed from nothing. And community building is never easier than technological research and breakthroughs.

We’ve seen active testers and growing transaction numbers after Shardeum’s testnet launch—excited to find others walking this innovative path—while also hearing skeptical voices. But we believe progress is spiral and winding, and every idea and exploration deserves a try.

As stated in “Baopuzi·Yongxing”: “A nation has six professions, and artisans are one of them. Some sit and discuss principles; others rise and act.”

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News