The Illusion of an Eternal Bull Market: Greed Has Nothing to Do With Centralization

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

The Illusion of an Eternal Bull Market: Greed Has Nothing to Do With Centralization

We are always repeating history.

Author: Beam @Jsquare

July's market is digesting the extreme volatility of the previous two months, as investors debate whether a cyclical bottom is forming. We now have time to reflect on what DeFi technology, CeFi collapses, excessive leverage, and liquidity cycles have taught us. Before every crisis, someone always believes "this time is different"—yet in reality, we keep repeating history.

Faced with market cycles, technological progress may raise economic expectations but cannot suppress greed and fear. We've witnessed the destructive power of leverage and the rapid bursting of bubbles. If there’s one lesson from the past two months, it must be respect for market laws and introspection into speculative psychology.

Nothing has changed—only that investors have learned more, while frenzy and noise are eliminated by the market.

✦ Collapsing Markets ✦

Using Glassnode data, we analyzed Ethereum’s monthly token price changes over the past five years since it gained broad consensus. The market slump between April 2022 and June 2022 stands out starkly. In June alone, ETH dropped 45%, and by the last day of the month, its price had fallen 78% from its all-time high of $4,808 in late 2021.

Figure 1: Monthly Ethereum Price Changes from June 2017 to June 2022

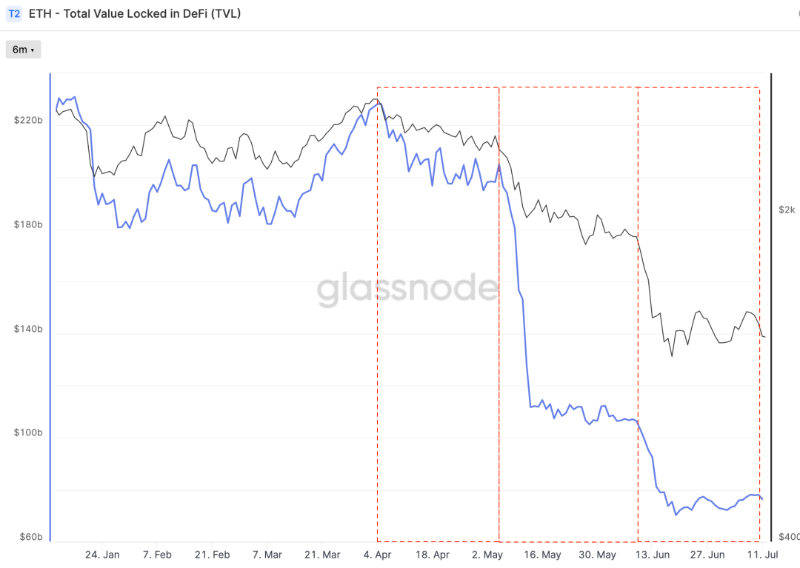

We focus on Ethereum rather than Bitcoin because this crisis may be more closely tied to liquidity dynamics. Despite the rise of various Layer 1 blockchains in recent years, since the emergence of DeFi, Ethereum has remained the dominant smart contract platform—hosting vast amounts of users, capital, transactions, and innovation—acting like a gravitational field constantly absorbing and releasing liquidity. As shown in Figure 2, gray represents Ethereum’s market cap and blue shows total value locked (TVL) across the network. Starting in 2020, during the bull cycle, both ETH’s price and TVL surged, peaking at approximately $253 billion in December 2021. After a partial retreat due to the collapse of numerous GameFi 1.0 projects by late 2021, TVL rebounded sharply to $228 billion in March–April 2022, then plunged steeply and continuously without recovery.

Figure 2: Ethereum Market Cap and TVL Changes from June 2017 to June 2022

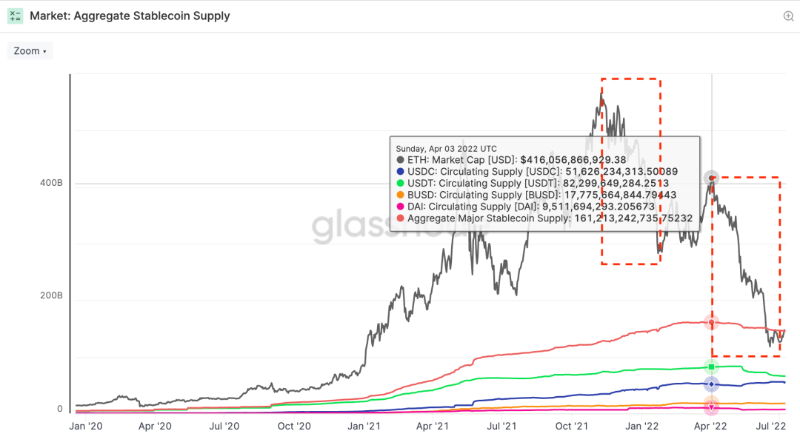

Another shift occurred in stablecoin supply on the Ethereum blockchain. In Figure 3, gray indicates Ethereum’s market cap, orange shows total supply of major stablecoins, and green, blue, orange, and purple represent USDT, USDC, BUSD, and DAI supplies respectively. Unlike the sharp decline in Ethereum’s market cap between November 2021 and January 2022, this downturn coincided with shrinking stablecoin supply—an unprecedented phenomenon. Stablecoin supply peaked at $161 billion on April 3, 2022, dropping to $146.5 billion by June 30, representing an outflow of $14.5 billion—more than DAI’s entire supply. Interestingly, during this period, the leading stablecoin USDT (green) saw declining issuance, while USDC (blue) appeared to act as a “safe-haven” stablecoin, experiencing modest growth.

Figure 3: Ethereum Market Cap and Major Stablecoin Supply from January 2020 to June 2022

This cascade of falling prices, shrinking TVL, and reduced stablecoin supply suggests this market shock is far more severe than the dip from late 2021 to early 2022—after all, capital or liquidity directly reflects market confidence and drives market vitality.

It should be noted that liquidity has two meanings in macroeconomics: one refers to how easily assets can be converted into cash (micro level), and the other refers to the abundance of capital in the market (macro level). In this article, we refer exclusively to the latter.

Looking back at the crash from April 2022 onward, we can divide this difficult period into three phases, illustrated in Figure 4, where gray denotes Ethereum’s market cap and blue shows TVL on Ethereum.

Figure 4: Ethereum Market Cap and TVL Changes from January to June 2022

● Phase One: April 4 to May 6 — Market decline was primarily driven by concerns about macroeconomic conditions. The Fed’s tightening stance intensified, confirming expectations of a 50bp rate hike at the May FOMC meeting and projecting up to 275bp hikes for the year. U.S. Treasury yields approached 3%, the dollar strengthened rapidly, appreciating from 6.37 to 6.5 against the RMB, and commodity markets hit new highs. BTC showed increasing correlation with traditional markets, and crypto began weakening, with Bitcoin falling below $40,000. As seen in Figure 4, both Ethereum’s market cap (gray) and TVL declined synchronously and moderately—suggesting sophisticated capital was simply pricing in expectations of tighter liquidity.

● Phase Two: May 7 to May 14 — The market drop was mainly triggered by the LUNA catastrophe. Within days, two top-10 digital assets (LUNA and UST) erased nearly $40 billion in investor value. On May 7, 2022, UST began decoupling from its peg. By May 9, it had fallen to $0.35, while LUNA traded around $60 (down from its ATH of $119). Over the next 36 hours, LUNA crashed below $0.10, and UST fluctuated between $0.30 and $0.82. This caused the LUNA-UST redemption mechanism to spiral out of control: amid panic and opportunism, users rushed to exchange 1 UST for $1 worth of LUNA, massively increasing LUNA supply and further crashing its price. Soon, South Korea’s so-called “national coin,” LUNA, was nearly wiped out. Figure 5 shows the BTC holdings of Luna Foundation Guard (LFG) (orange line), revealing how their BTC reserves—built since March to anchor UST to the broader BTC market—were completely depleted in a single day on May 9 as they desperately tried—and failed—to defend the dollar peg.

Figure 5: Bitcoin Price and LFG’s BTC Holdings from January to June 2022

● Phase Three: June 8 to June 19 — The market plunge stemmed largely from CeFi institution failures. Rome wasn’t built in a day, but it can fall in one. With DeFi protocols already fragile, LUNA’s fallout proved deeper than expected, even affecting Lido, causing stETH to depeg (though strictly speaking, stETH isn't pegged to ETH—it functions more like an ETH futures contract). Celsius was the first domino to fall, suspending all withdrawals. Then came news that Three Arrows Capital—a key supporter of LUNA and a major holder of stETH—faced over $400 million in loans coming due. Compounding the crisis, according to Sean Farrell, Head of Digital Asset Strategy at FSInsight, Three Arrows founders Su Zhu and Kyle Davies leveraged their reputations to “borrow recklessly from almost every institutional lender in the industry,” including Voyager Digital, Babel Finance, and BlockFi. They acquired most of their assets through debt-fueled leverage with minimal collateral. Suddenly, off-chain exchanges, lending platforms, and hedge funds were all vulnerable—unable to repay debts, starved of liquidity, or forced into liquidation. Other affected institutions and individuals followed suit, withdrawing liquidity to protect themselves. On June 18, BTC fell below the 2017 peak of $20,000, hitting a true low of $17,708.

✦ History Repeats Itself ✦

Roger Lowenstein wrote a book titled *When Genius Failed: The Rise and Fall of Long-Term Capital Management*, chronicling the rise and fall of LTCM. One quote stands out: derivatives are new, but panic is as old as markets.

That year was 1998.

Derivatives such as options and futures—now commonplace—were still considered financial innovations back then.

LTCM was founded in 1994 by the former bond trading head of Salomon Brothers, pursuing high-leverage arbitrage strategies in fixed-income markets. Its board included Myron Scholes and Robert C. Merton, who won the Nobel Prize in Economics in 1997 for developing the famous Black-Scholes model for option pricing.

At its peak, LTCM employed a seemingly simple strategy—mean reversion—betting that markets would eventually return to historical norms. The underlying assumption was that deviations from the “norm” wouldn’t last long. For years under normal conditions, this held true. LTCM delivered annualized returns of 21%, 43%, and 41% in its first three years, attracting Wall Street’s elite. The fund entered thousands of derivative contracts, making nearly every major bank a creditor, with exposure exceeding $1 trillion.

But the mean-reversion bet failed—or rather, LTCM didn’t survive long enough to see markets normalize. A black swan struck: Russia’s financial crisis sparked global panic, prompting investors worldwide to sell everything. The yield spreads LTCM had bet on didn’t converge—they widened. Suddenly, tens of billions in leveraged trades turned sour. Forced liquidations followed, amplifying systemic risk across the entire financial system.

Many compare Three Arrows Capital’s collapse to LTCM’s downfall.

While Three Arrows pales in scale—peaking at $18 billion compared to LTCM’s massive footprint—the narrative bears striking similarities.

LTCM bet on mean reversion, borrowing heavily to run highly leveraged strategies. When a black swan hit, the strategy failed, debts couldn’t be repaid, liquidity dried up, pricing distorted, and faith collapsed.

Three Arrows bet on LUNA and stETH, borrowing extensively with low or zero collateral, running ultra-leveraged positions. When LUNA imploded and stETH came under pressure, Three Arrows was forced to dump stETH to limit losses. Unable to meet widespread debt obligations, they inflicted massive damage on companies like Voyager Digital, BlockFi, and Genesis. Even investors uninvolved with LUNA or stETH pulled liquidity. The market underwent a brutal deleveraging and hard landing.

1998 and 2022—24 years apart—yet the progression is eerily similar. Not to mention the dot-com bubble in 2000 or the subprime mortgage-triggered global financial crisis in 2008—history keeps repeating itself.

During periods of leverage buildup, did no one reflect? Did no one learn from history?

No—surely some did.

But their voices were drowned out by surging asset prices. Optimists shouted louder: “This time is different.”

In 1998, Wall Street worshipped derivatives and Nobel laureates. During the dot-com bubble, people believed communication technology would open a new era. In 2008, subprime mortgages seemed to liberate humanity.

Technological breakthroughs breed optimism, fuel speculation, erode risk awareness, accumulate leverage, promise unrealistic returns—and when the dominoes fall, nothing is different.

✦ Technology’s Essence and the Leverage Cycle ✦

Brian Arthur, winner of the Schumpeter Prize, argues in *The Nature of Technology* that the economy is an expression of technology, and technology itself is based on combination and recursion. Combination refers to rapid integration, while recursion means directional, optimized replication.

“Composability” accelerates innovation exponentially.

I believe this is why DeFi has been so celebrated since its inception. At its core, DeFi resembles Lego blocks stacking together. This composability shortens innovation cycles—we stand on the shoulders of giants. Imagine if OHM weren’t open-source or Curve held patents—how difficult would building a ve(3,3) model from scratch be? Precisely because of syntactic composability, protocol reusability, and tool compatibility, after Uniswap ignited the DeFi Summer, we’ve seen remarkable growth across the crypto landscape. We don’t need to reinvent the wheel—just focus on areas needing technical breakthroughs.

Now let’s examine how those dominoes were quickly erected—and then swiftly toppled.

From the start, the algorithmic stablecoin protocol behind LUNA-UST sparked fierce debate. Critics called it a Ponzi scheme in disguise; others dismissed it as “stepping on your own feet.” It introduced a novel narrative and technical approach—using algorithms instead of asset-backed reserves (like USDC, USDT, or DAI) to maintain a 1:1 USD peg. Delphi even built a DeFi paradise around this story—Anchor Protocol—offering a 20% risk-free yield to absorb these newly minted assets.

No backing, decentralized, algorithm-driven, protocol-based—like the Bible says, a new heaven and a new earth, where the sea is no more.

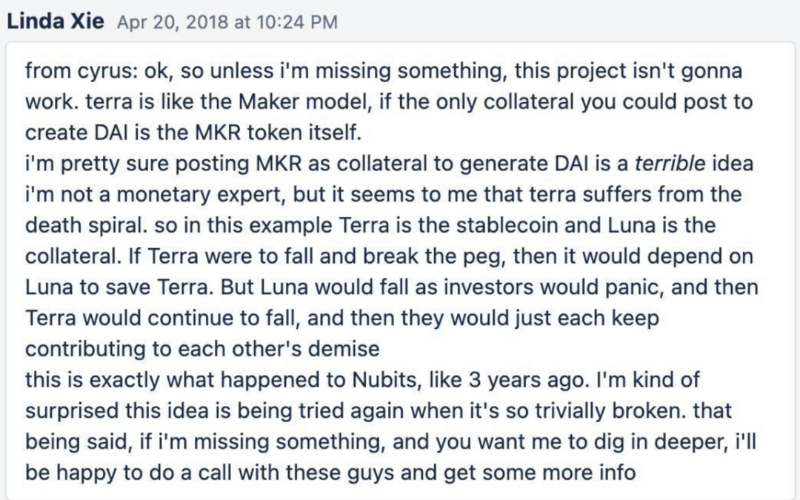

Even as LUNA rose, warnings surfaced. As early as 2018, Cyrus Younessi, MakerDAO’s risk officer and former Scaler analyst, explained to Scaler why he believed Terra/LUNA wouldn’t work, citing Nubits’ failure three years prior as proof that such experiments repeatedly fail in the market.

Figure 6: Cyrus explaining Terra’s death spiral, image from Twitter

Yet until 2022, LUNA kept rising, and Do Kwon confidently made public bets on Twitter. Time seemed to prove LUNA was different from Nubits—this time really was different.

The perceived difference mainly came from Anchor and LFG.

From the beginning, DeFi stories have always revolved around liquidity.

DeFi’s three pillars: DEX, Lending, and Stablecoins. In terms of liquidity: DEX is where liquidity is exchanged, Lending is where liquidity is priced, and Stablecoins anchor liquidity.

If you want to create a myth of stability, you must answer: where will this newly created liquidity go? If liquidity is water, the market needs a sponge to absorb and lock it in place. With this in mind, in July 2020, LUNA launched Anchor, which Nicholas Platias described in a Medium post.

He envisioned a savings protocol with the following features:

-

Principal Protection: Anchor implements liquidation mechanisms to seize borrowers’ collateral when loans become risky, protecting depositors’ principal.

-

Instant Withdrawal: Terra deposits can be withdrawn immediately—no lock-up required.

-

Stable Interest Rate: Anchor stabilizes deposit rates by transferring variable rewards from staked assets to depositors.

Eventually, they set this stable rate at 20%.

Under normal circumstances, any investor educated in finance would be alarmed by such a yield.

The simplest reason: the Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM). For any given asset, expected return correlates only with systematic risk. Anchor’s promised 20% fixed return vastly exceeded the market’s risk-free rate—implying this return could not possibly be risk-free.

At its peak, UST’s market cap reached $18 billion, with over $14 billion locked in Anchor, requiring $2.8 billion annually in yield payments. No matter how much underlying staking and lending occurred, such returns were unsustainable. Markets are simple: without taking commensurate risk, you cannot earn above-risk-free returns. Thus, LUNA needed a way to cover the yield gap.

In January 2022, another mechanism complementary to Anchor emerged—LFG launched. On January 19, Do Kwon announced the creation of the Luna Foundation Guard, an organization “authorized to build reserves supporting the dollar peg under volatile market conditions” and to “allocate resources to support Terra ecosystem growth” via grants. Estimates suggested Anchor burned over $4 million per day from LFG’s coffers.

Back in May 2021, the LUNA-UST mechanism had already triggered a death spiral once. LFG used its deep pockets to inject capital, restoring UST’s peg—unintentionally reinforcing market confidence.

Anchor offered yields far above the risk-free rate, and LFG fueled market euphoria. People forgot basic financial principles. Leverage exploded: burn LUNA to mint more UST, deposit into Anchor, use receipt as collateral in other protocols (e.g., Edge), borrow more UST, redeposit into Anchor—creating a recursive loop. Each layer added bricks to UST’s towering house of cards.

Individual investors had limited access to capital and information, whereas sophisticated “arbitrageurs” (CeFi institutions) enjoyed better funding and opportunities. Leverage allowed them to hold larger positions. Yet even they faced margin constraints—except Three Arrows, which engaged in extraordinary leverage, borrowing assets uncollateralized.

As people celebrated LUNA’s success and major chains rushed to copy it, the market embraced unfounded confidence and unsustainable speculation. As credit bubbles grew, speculators emerged, zealously preaching the gospel. Months ago, casually browsing Twitter would flood you with LUNAtics spreading the holy grail narrative, luring new investors into the same spiral.

But when bad news hits, asset values fall alongside arbitrageurs’ wealth. Leveraged traders face margin calls and are forced to sell assets to meet requirements. Selling pressure further depresses asset values, triggering more margin calls and forced sales. Rising volatility and uncertainty accelerate deleveraging. The resulting margin shifts imply falling leverage. Hence, due to leverage, price drops are magnified beyond normal levels.

Over-leveraged in good times, over-deleveraged in bad.

Even the most innovative technology, strongest funding, and firmest market consensus can be shattered in a “black swan” event. No matter how unique the technology or narrative seems, the leverage cycle still reigns supreme.

✦ Greed Has Nothing to Do With Centralization ✦

In social and economic life, we inevitably face multi-party distrust, especially in finance. Traditional finance solves this by relying on notaries, lawyers, banks, regulators, and governments to provide “trust services”—invisible costs borne by every participant.

DeFi—short for Decentralized Finance—offers an alternative solution to trust among individuals. It aims to create a financial world without intermediaries, extending blockchain’s use from simple value transfer to complex financial applications. Its core tenets include censorship resistance, immutability, verifiability, accessibility, and social consensus. It promises an open, permissionless financial future—anyone can access financial services, understand transparent risks, and trust their money won’t be stolen or frozen.

Yet despite these proclaimed benefits, crypto investors still engage with CeFi institutions.

Before proceeding, let’s define CeFi. Here we exclude traditional centralized financial institutions like banks and brokers, focusing solely on centralized crypto financial entities, such as CEXs like Binance and FTX, and lending platforms like BlockFi.

The reason? CeFi offers some of DeFi’s yield advantages plus the usability and perceived safety of traditional financial products. So despite counterparty risk, hacking threats, fraud, and other dangers, users willingly move their assets from fully self-custodied on-chain wallets into black boxes. In doing so, users appear to weigh trade-offs—sacrificing full ownership of their funds for greater convenience and ease of use.

These black boxes should, in theory, employ systematic risk controls—over-collateralization, leverage limits, liquidity safeguards—to withstand market swings. But when human greed runs wild, it's extremely difficult to detect warning signs inside these opaque systems.

What about DeFi—can a system touting immutability, verifiability, and accessibility truly curb human greed and fear?

In 2013, Vitalik Buterin foresaw smart contracts enabling complex financial applications.

Software and algorithms governing interactions—"code is law"—represent another form of regulation, allowing private actors to embed values into technological artifacts. This brings many benefits: automated legal enforcement, pre-defined rule execution, automatic compliance. Blockchain technology exemplifies this best, unlocking new ways to turn law into code. By converting legal or contractual terms into enforceable “smart contracts,” rules are automatically executed by the underlying blockchain network—always as intended, regardless of parties’ intentions.

As Robert Leshner, founder of the DeFi lending protocol Compound, once said: no human judgment, no human error, no manual processes—everything is instant and autonomous.

Relying on technology to constrain behavior and enforce rules sounds ideal. Many “code is law” advocates seem to think DeFi operates entirely outside legal frameworks, rather than merely disintermediating financial institutions.

Yet just because something happens on a blockchain doesn’t mean centuries of legal procedures suddenly cease to apply. Regulating via code has significant limitations and flaws—potentially creating new issues around fairness and due process. Code itself reflects human intent. Without stronger external constraints, it’s hard to imagine anyone using technology to restrain their own greed.

Let’s revisit LUNA again. The LUNA-UST arbitrage mechanism was indeed implemented in code, making the process automatic, smooth, and fast under normal network conditions. That’s technological progress. But technically flawless execution doesn’t solve problems beyond arbitrage—risk, leverage, and bubbles remain untouched.

This was a faster-than-ever bubble burst, engulfing both on-chain DeFi protocols and off-chain CeFi institutions. Within weeks, no one escaped. In the face of the leverage cycle, our endless debates about DeFi vs CeFi—differences, futures, superiority, salvation—become meaningless.

We’re not suggesting that curbing human nature requires universal laws—whether regulation should act as gatekeeper or merely as a bell-ringer, as classical economics posits. We simply emphasize the importance of respecting market规律 and restraining speculative psychology—issues neither DeFi nor CeFi technologies alone can resolve. True resolution depends on overall market maturity and collective growth among crypto investors, moderating excessive leverage cycles. After all, in a truly efficient market populated by rational investors, such distorted opportunities wouldn’t persist for long.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News